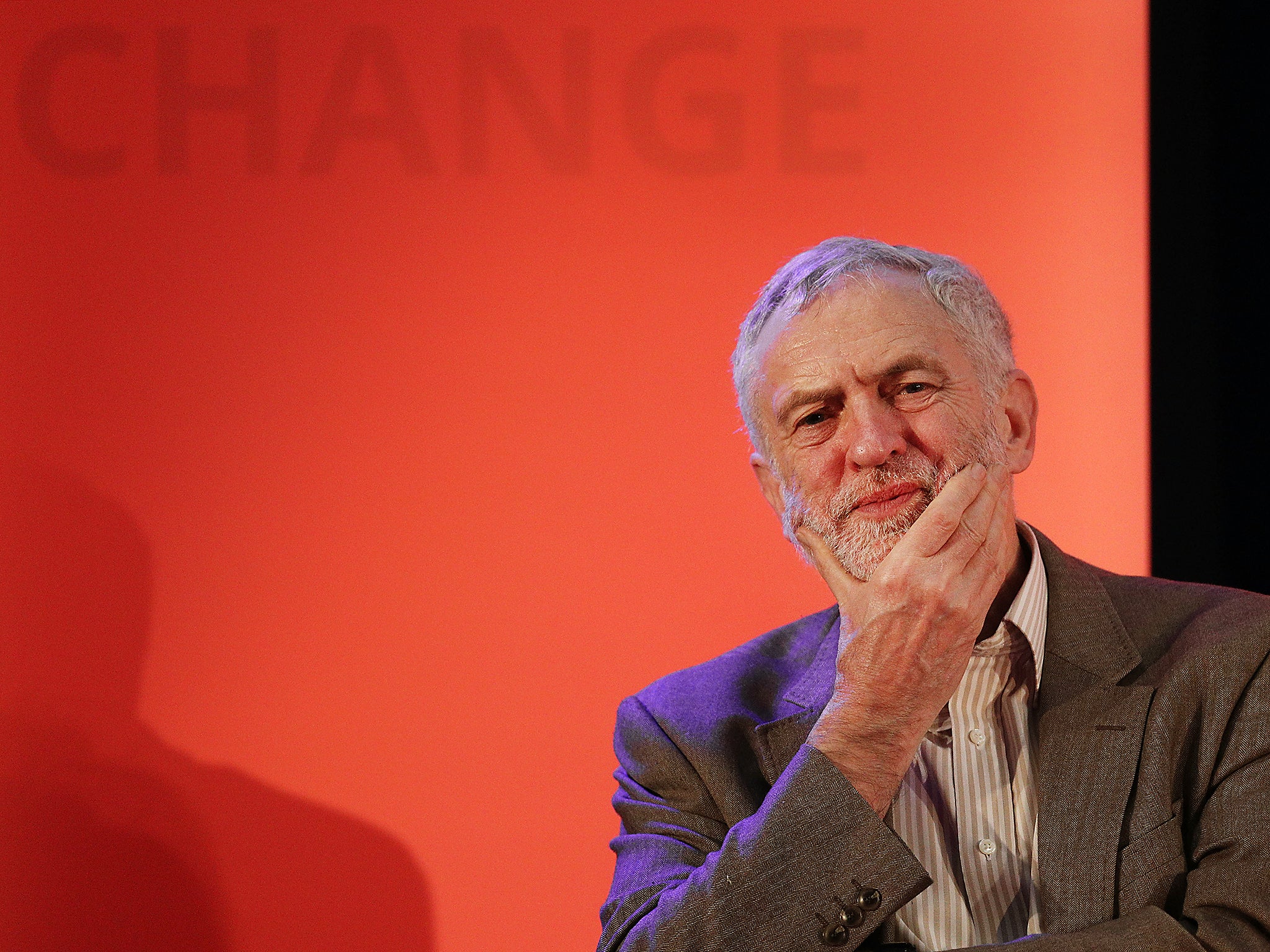

Jeremy Corbyn could trigger the next populist political earthquake – unless he is failed by his own complacency

Corbyn, who is being rebranded as a populist leader for 2017, will find it difficult to balance a rejection from Westminster politics as usual with leading and managing Labour’s 231 MPs

Labour’s top strategists plan to begin 2017 by rebranding Jeremy Corbyn as a “populist”. The last year delivered a series of major defeats to the liberal mainstream and Corbyn’s team now aims to capitalise on this rising tide of anti-establishment politics. But what might this shift in strategy actually involve? And how might a populist turn boost the electoral chances of Corbyn and the Labour Party?

Populism has been used as a term to describe and explain movements as divergent as Donald Trump's victory in the US and the rise of the left-wing Podemos in Spain. In its loosest sense, “populism” could include any mobilisation of popular grievances against the status quo.

Populist leaders present themselves as distinct from a political and corporate establishment, claiming to represent “the people” more directly than those currently holding and executing power. Populist movements differ only by who is included within the category of “the people”, and who – or what – is defined as its enemy.

By adopting the rhetoric of populism, Corbyn’s team are thus signalling a new political strategy: to define him against the political establishment through ramping up his outsider status. Like Trump, Corbyn can quite genuinely present himself as removed from the establishment and uniquely capable of reforming a corrupt political system. Unlike Trump, however, his populism will depend not on the "othering" of foreigners but on highlighting how a Westminster dominated by business and political elites has systematically worked against the interests of ordinary people.

A populist turn like this represents a paradigm shift for Labour in two ways. Firstly, it breaks the New Labour habit of trying to outdo the Conservatives purely on the concept of economic competence. Instead of a contest over technocratic ability with regards economic management and public service provision, a populist approach would frame the next election through a rejection of the vested interests which currently shape policy formation.

Second, the populist approach brings to an end the attempt to make Corbyn look and sound like a conventional politician. From the national anthem controversy to questions around his dress sense, the issue of Corbyn’s non-traditional style have dogged the first year of his leadership. A populist strategy turns this perceived weakness into a strength by making him the face of anti-establishment demands.

This week we saw the first application of a populist media strategy by Corbyn and his team. In response to a side-swipe from Obama, Corbyn posted three tweets rallying against the establishment, advising that both Labour and the Democrats must “challenge power” in the wake of Hillary Clinton’s defeat.

Along with the message, the medium in which it was delivered speaks volumes about Corbyn’s new approach to political communication. At root, populism is about speaking directly to the population, bypassing the traditional political infrastructure of Parliament and abandoning the reliance on the dedicated “spokesperson”. Consequently, populist politicians tend to exploit unmediated media channels. For Silvio Berlusconi or Pablo Iglesias, this meant chat shows appearances. For Trump and now Corbyn, Twitter provides an even easier route to intervene in the news cycle. The effectiveness of such an approach was confirmed when headlines reported Corbyn had “hit back” against the President’s affront. Such coverage is gold dust for a politician consistently portrayed as too weak to lead a party or nation.

Despite these positive signs, two barriers may prevent him from achieving populist success. The first is the UK’s parliamentary system. In the US, where Trump and Bernie Sanders both ran successful populist campaigns, presidential candidates enjoy greater autonomy from their parties than their UK equivalents. Ukip’s Nigel Farage and Podemos’s Pablo Iglesias both built new parties in their own image. Jeremy Corbyn, on the other hand, will find it difficult to balance a rejection from Westminster politics as usual with leading and managing Labour’s 231 MPs.

The second and arguably greater obstacle could be complacency. Team Corbyn has not succeeded in defining a simple political message or an electoral strategy thus far. Corbyn’s Labour has shied away from a full attack on Westminster “elites”. Ed Miliband faced a similar dilemma before the 2015 general election, unsure whether or not to embrace a more aggressive rhetoric of “the people” versus “the establishment”.

Ahead in the polls, Miliband played it safe and chose the discourse of the centre. This route is closed to Corbyn. Labour’s woeful poll ratings will both encourage and necessitate a more radical approach.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies