Why are so many Indians being forced to work in war zones?

Despite India’s economy being one of the fastest growing in the world, rates of unemployment and the quality of the jobs on offer remain a huge concern for millions. Namita Singh reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Pat Nibin Maxwell moved from India to Israel at the height of the Gaza conflict in December last year, leaving behind a pregnant wife and a four-year-old daughter. The decision to relocate to another country in search of work was not an easy one, particularly to such a restive region.

It was a choice driven by “financial reasons”, his cousin Jose Dennis tells The Independent. Maxwell was among hundreds of Indian youths taking up blue-collar jobs in dangerous locations, including Russia’s frontline with Ukraine, driven by what an economist describes as “extreme desperation” due to the lack of well-paid employment in India.

On 4 March, Maxwell’s family were told on a call that the 31-year-old was grievously injured in an anti-tank missile strike on a poultry farm in northern Israel. “He was hospitalised along with two other Indians,” Dennis says. “Later, we learnt that he has died.”

The decision to take up work in conflict zones comes with high risks despite the fact it is backed by the government in some cases. The Narendra Modi administration has signed an agreement with Israel to allow 40,000 Indians to work in the fields of construction and nursing in the Middle Eastern country, making up for the loss of Palestinian workers amid the Gaza war.

The Indian government’s move led to criticism in some quarters, with opponents of the scheme questioning why better, safer job opportunities couldn’t be made available closer to home.

At the time the scheme was announced, the government said India was committed to making sure its migrant workers were protected. “Through this agreement, we want to ensure that there is regulated migration and the rights of the people who go there are protected,” said Randhir Jaiswal, spokesperson for India’s foreign ministry.

Confirming the news of Maxwell’s death and the injury to two others due to a “cowardly terror attack” launched by Hezbollah, the Israeli embassy in India said in a post on X it was “deeply shocked and saddened”.

“Our prayers and thoughts naturally go to the families of the bereaved and those of the injured. Israeli medical institutions are completely at the service of the injured who are being treated by our very best medical staff. Israel regards equally all nationals, Israeli or foreign, who are injured or killed due to terrorism,” the post said.

In Kollam, Maxwell’s family are struggling to come to terms with the loss. As well as his wife and young daughter, he is survived by his elderly parents and two brothers, his relatives said. “It is a very difficult time for us. We are running [around] and making arrangements to receive his body,” his cousin says.

Maxwell had an industrial training certificate and was working with a manpower supply firm in the UAE before he quit in December to move to Israel. “Nibin’s brother-in-law, who works as a caregiver in Israel, had helped him to get the job,” his father, Antony Maxwell, told the Indian Express.

“A week after Nibin left for Israel, his brother Nivin also followed. Nivin, who worked at a private firm in Bengaluru, is also employed in the agricultural sector in Israel. The two moved to Israel considering the better prospects.”

Israel’s suspension of work permits for tens of thousands of Palestinians following the Hamas attacks on 7 October last year created a massive labour gap in the country, opening up blue-collar job opportunities for workers in countries such as India. It started offering visas for employment in the construction and agricultural sector, with about 800 Indians moving to the country in December.

By February, tens of thousands of workers were filling job centres across India, spotting opportunities in the acute labour shortage.

Anoop Singh, a college graduate and construction worker, was told he would make about £1,200 a month if he was selected to go to Israel – significantly more than the £282 to £330 he could get as a monthly wage for the same work in India.

“That’s why I have applied to go to Israel,” he told the Associated Press as he waited at the centre in Lucknow, the capital of India’s most populous state of Uttar Pradesh, for his job interview.

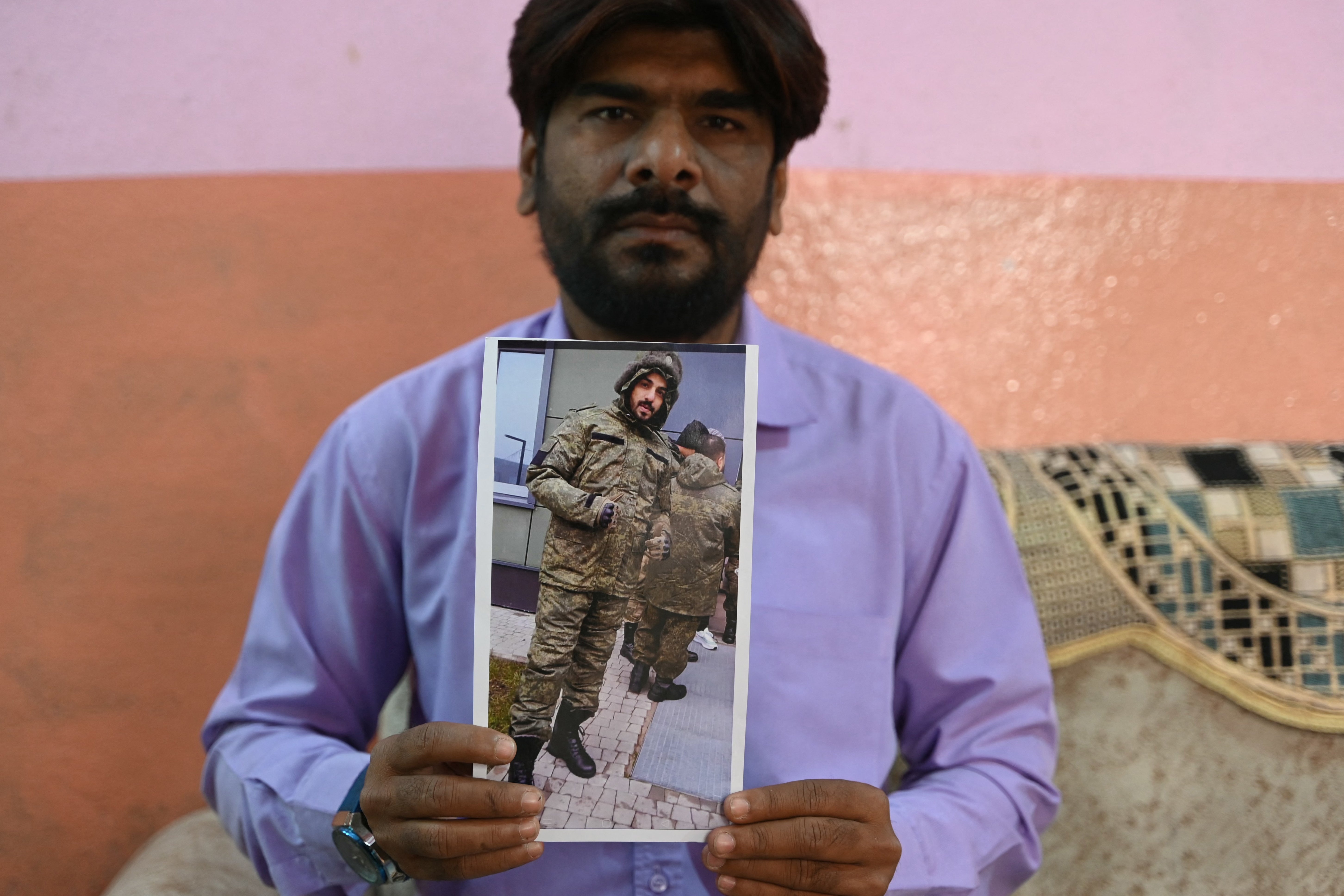

Israel is not the only destination for Indian workers in search of a job, regardless of the risk. There are growing media reports of Indian nationals being unwittingly recruited to join the Russian army in its invasion of Ukraine after they moved countries in response to adverts for jobs seeking “army helpers”.

On Wednesday, the Indian embassy in Russia said it had “learnt about the tragic death of an Indian national Shri Mohammed Asfan”. Asfan, a clothes seller from Hyderabad, travelled to Russia via Dubai in November seeking work. His family say he was “duped” by a Middle East-based agent and did not know he would be forced to fight on the frontline, where he was killed.

“You don’t have to fight,” says Dubai-based agent Faisal Khan on his YouTube handle BabaVlogs in a post seeking such “helpers” from India. “All you have to do is to clear demolished buildings, look after armories and after a year of service you’ll be eligible for permanent residency."

Upon landing in the country, the recruits reportedly find the reality is very different – that they are quickly shipped to the frontline.

One of Khan’s recruits, an unemployed graduate from Uttar Pradesh, told AFP that he was deployed in eastern Ukraine’s Donetsk region after receiving basic arms training. “I was hurt in the fighting and taken to the hospital,” he told the agency. “I somehow escaped.”

Khan has said he was not aware that some “helpers” were being utilised like this.

In a statement last week, the government of India acknowledged that it was “aware that a few Indian nationals” have signed up for “support jobs” with the Russian army as it urged them to “stay away” from Russia-Ukraine war.

“The Indian Embassy has regularly taken up this matter with the relevant Russian authorities for their early discharge,” said Jaiswal.

Economists say that recruitment drives for blue-collar jobs in Israel and Russia cast an unflattering light on the cracks in India’s growth story. On the one hand, the message championed by prime minister Narendra Modi is that India’s economy is the fastest-growing in the world, a bright spot amid an otherwise gloomy global outlook, as the government invests in big-ticket infrastructure projects to woo businesses and foreign investors.

The government has been reluctant to release official unemployment figures, however, and the opposition says rising joblessness and the quality of jobs offered in the country are huge points of concern at a time when India has become the world’s most populous nation.

“We need to understand, of course [that] India has always been witnessing out-migration,” says A Kalaiyarasan, an economist and assistant professor at the Madras Institute of Development Studies. “There used to be a Gulf migration with South Indians going to Gulf countries or people from Punjab going to Canada. You can find some pockets within Tamil Nadu, going to Singapore.”

But these migrants are looking for opportunities for a longer time, better than what they have at home and in countries where they see themselves settling in, or returning after a few years but with a lot of money, he tells The Independent. This is patently not the same with people going to Russia or Israel.

“Now the people who go desperately to these war zones are not just looking for better prospects but are now driven by extreme forms of desperation. And that would differentiate this international migration from the others.”

After a rise in salaried jobs in the last two decades, the pace of regular wage jobs has stagnated since 2019 because of the coronavirus pandemic and an overall growth slowdown, according to the State of Working India report by Azim Premji University. The report says that while unemployment is falling, it is still high — above 15 per cent for university graduates of all ages and around 42 per cent for graduates under 25.

This drop in unemployment also has its caveats, as Kalaisaran highlights the Indian economy’s failure to create the same number of decent jobs as it used to before.

“So, even when someone says they are employed, what kind of employment is there? Are they really happy with that? Is it really what they want to do?” he asks as he gives the example of those employed in the gig economy. According to some estimates, it employs up to 10 to 15 million people in India and as per a Nasscom report, it is expected to expand to 23.5 million by 2030.

“Ask say Swiggy and Zomato (delivery) guys. Most of us think it is a job. Many of the graduates and engineers are actually opting for these jobs after their degrees. Ask them why they are doing it and they will say, they are looking for better opportunities.

“But now the better jobs and decent jobs have become very bad and very, very rare despite our economic recovery.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments