When the crunch of metal on metal came, the "black box" recorder documented it all – the exact position, the force of the crash, what was happening in front and behind. When investigators came to work out what had caused the unfortunate event, the device was recovered from the wreckage and many questions were answered. The passengers walked away with scratches. But then occupants have less than an 8 per cent chance of death in a two-car collision.

Yes, car collisions. The black box, or flight recorder, as it is commonly called, may have been a gadget designed to document a commercial aircraft's flight – its telemetry and performance, and the crews' communications with air traffic control and each other. But the technology is now being reimagined for cars, too.

Take, for instance, the new Smart Black Box developed by the US company KCI Communications. It constantly records video footage on a loop, saving the past 15 seconds and the next five should its motion sensor detect an accident. It will record where it happened, what time, your speed, whether you used the brake or indicated. Future models may also record what you were doing at the time, be it being fully in control of your vehicle or texting your mother while popping on a CD.

"The more laws there are, the more people try to find their way out of facing them, but black box evidence is concrete for anyone facing litigation," suggests KCI's vice-president, Chris Pflanz. "People don't think rationally in a car accident. Cars are much safer now, of course, but we're also so much more distracted. As the complications of driving have increased, it was inevitable that the black box idea would be borrowed from aviation. It's another barrier of protection."

Albeit one that, as Pflanz concedes, is a luxury compared with the benefits of knowing why an aircraft crashes – and the knowledge that may later help to prevent great loss of life under similar circumstances. The data from the black box recovered from Pakistan's worst-ever plane crash, this July, is currently undergoing analysis. Not so that of the Air France aircraft that crashed over the Atlantic last year. It has taken until this summer, and $40m, to narrow down its location to within a 5km zone, but still it remains elusive and the cause of the crash unknown.

But this rare occurrence is to belie what a marvel of technology the black box is, given the information it records and the extremes that it must survive to do so. That means a collision, for example, equivalent to deceleration from 450kph to a dead stop over 45 centimetres; an impact equivalent to a 225kg steel spike dropped on to it from three metres above; 2.3 tons of force from all directions; the crushing pressures of 20,000ft under the sea; corrosion – it must be able to survive 30 days in salt water, and its emergency beacon must remain in operation during that time; and it must be able to survive 1,000C heat that, increased by burning aviation fuel, can soften steel.

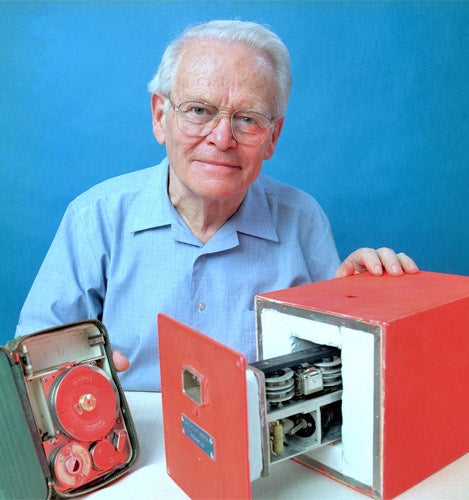

The recorder is not expected to survive intact – only the information data inside it. That was the bright idea of one David Warren (above), an Australian chemist who died this summer aged 85, brought on as an expert in fuels during the investigation of 1953's crash of the first commercial passenger jet aircraft, the De Havilland Comet. Realising that the investigation would be hugely advanced if investigators knew key information about the aircraft and pilot action at the time of the incident, by 1958, he had built a prototype using steel wire to record four hours of just that.

Remarkably, the wider aviation industry rejected the idea, pilots especially, who claimed that it would be akin to being spied on. "No plane would take off with Big Brother listening," as a Federation of Air Pilots statement had it. The UK authorities – the Comet had been a British aircraft – moved to make the fitting of recorders compulsory, with the US issuing a mandate for its fitting on certain aircraft. Only in 1967 did Australia become the first country to make flight data and cockpit voice-recording compulsory. Today's fully digital systems are able to record a wider band of information for up to 25 hours. The US Federal Aviation Administration, for example, stipulates that at least 88 different parameters are now recorded, though many units record 300 or more, compared with some five for early recorders.

But a new-generation black box is reaching for the skies. Recent advances have, for example, seen them retro-fitted with an independent power source in a bid to mitigate the consequences of one necessary compromise. Flight recorders are typically housed in the tail of an aircraft, so that the fuselage can act as a crumple zone on impact. But this risks the severing not only of power cables running the length of the aircraft, but also of data cables, meaning the last crucial seconds may not be recorded. So now all new aircraft are built with two recorders, one nearer the cockpit. The front-runners of new ideas include a deployable recorder – so that it is ejected away from the crash site on impact – and systems that, in parallel with an onboard black box, continuously stream data and cockpit recordings to a hub on the ground, piggy-backing on other air-to-ground transmission. The cost of a comprehensive system remains considerable – up to five times that of a conventional black box for the hardware alone, on top of the cost of the huge bandwidth needed to transmit massive amounts of data – as are the technical challenges of both storage on the ground and streaming without interruption from high altitude or when the aircraft is in a steep dive.

"It's unacceptable that there could be an incident of [the Air France crash's] magnitude and not a faster response," says Matt Bradley, the vice-president of business development for AeroMechanical Services, now in design partnership with L-3, the world's biggest manufacturer of flight-recorder technology. "The problem is that nothing moves fast in the airline industry, which has also never exactly seen black box technology as a revenue-generator."

Hybrid systems, which, less expensively, just send unusual data, or which stream by utilising a combination of satellites, the internet and the latest antennas technology, are what we are likely to see established within the next six months. AeroMechanical Services already has just such a system working in some 200 aircraft, across 25 operators, so interest is there. The EU and the International Civil Aviation Organization have launched a study into streaming technology, too, following in-flight trials this summer. Some in the industry feel it is a matter of time before streaming becomes standard. Others feel the money is better spent making conventional recorders tougher still and more easily recoverable.

Remarkably, that question of privacy remains, too. A long-running proposal to install cockpit video recorders in passenger aircraft has been met with the same objection that stalled the black box's use when it was invented half a century of crashes ago. The Air Line Pilots Association in the US has argued that cockpit voice recordings have already been used for "sensational purposes" by the media, by litigants in civil and criminal cases, even by employers for disciplinary purposes.

Which perhaps begs the question: do we want black box recorders in our cars? They do in New Zealand. A spate of attacks on taxi drivers across the country this past spring saw the government there recommend the installation of black box-style devices, with local firm Logical Systems suddenly seeing a rush for its T-Eye Event Data Recorder, the "automotive digital witness", as it has been billed. It even has infrared so will record in the dark.

Indeed, just as further advances in the airborne version are inevitable, so too is the widespread adoption of the in-car black box. The appeal is not just to insurers, but to car-makers, who may be able to use such devices to head off component failure and, by linking the devices to the mobile phone network, also to governments aiming to improve road safety records and emergency services response times.

A draft bill that would require new cars and lorries to carry a black box was released by the US government earlier this year, and a three-year study by the European Commission's transport arm has recommended their mandatory installation. It seems we respond to being policed. The EU found that drivers with black boxes were 10 per cent less likely to be involved in a fatal accident. Even the police respond to being policed – when the Metropolitan Police installed them in their cars in 1999, there was a £2m reduction in accident costs over the following 18 months.

But then Big Brother's black box is becoming all the more personal all the time. The police now routinely wear button-activated Body-Worn Videos around Saturday night trouble spots, while Microsoft's SenseCam is a badge-sized prototype gadget triggered by movement or changes in light level or temperature to capture up to 4,000 images a day, building a visual record of all that you have seen and done. Reviewing one's SenseCam pictures is said to encourage Proustian moments, in which one image can prompt the recall of a flood of detail. It could prove the perfect tool for life-blogging times in which the recording of mundane events appears to have become a reflex action, as well as for those suffering increasingly manic lives. But just how long before we are obliged to carry one?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies