The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Unlock the Florida Keys

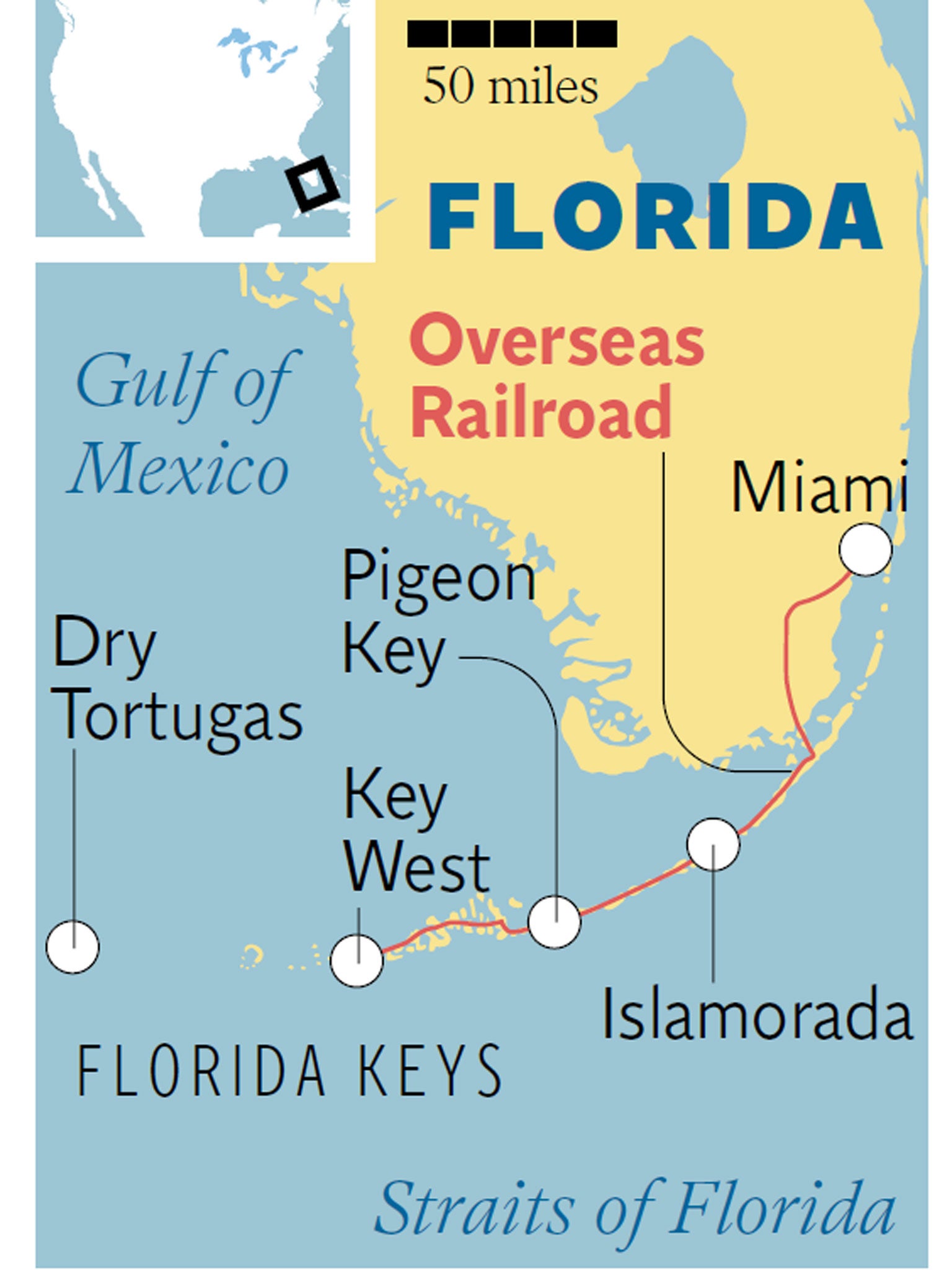

Kate Eshelby traces the tracks of the old railroad that once connected these tropical islands

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is eerily quiet. A strawberry-red sun melts over the water. Nearby is a bridge, but it leads out into the sea and then stops dead, as if it had changed its mind. This is Pigeon Key, a tiny island in the middle of the ocean, part of the Florida Keys and once a worker's camp for one of the world's greatest railways. It stands below the giant bolsters of the Seven Mile Bridge, which forms part of a rail route that was completed in 1912. This ribbon of metal finally linked the far‑flung Keys to mainland America, changing them for ever.

The Florida Keys is an eccentric tropical archipelago of more than 800 islands, tailing out from the end of Florida, between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean. The Overseas Railroad took seven years to complete, built over swampland and miles of open sea in terrible, mosquito-ridden conditions. Forty-two narrow, single-track bridges stretched over the water and train passengers could look out from the comfort of their seats and see turtles swimming offshore from the comfort of their seats.

I was following its route: a slice of history that has been turned into one long, open road called the Overseas Highway. The oil baron, Henry Flagler, built the railroad using $50m of his own money, yet his masterpiece was destroyed by the 1935 hurricane – one of the strongest ever to hit Florida. It was abandoned because it was too expensive to rebuild. The new road was laid on top of the surviving train trestles and bridges. Many of the original bridges, piers and viaducts remain, and Pigeon Key has many of the original railway's bygone buildings. The Florida Keys Overseas Heritage Trail follows the Highway at various sections – a paved route for walkers and cyclists that is gradually being extended.

My first stop was Islamorada, meaning "village of islands". Here I was staying at the Casa Morada, a small hotel in a quiet back street surrounded by tropical gardens. It's beautifully decorated – contemporary mixed with Mexican antiques – and has its own tiny sand island, reached across a small bridge, with a pool and swaying palm trees.

From there I took a boat across to Indian Key and explored this now uninhabited island with its ruins from the early 1800s. In 1830, a New Yorker called Jacob Housman bought the island as part of his thriving wrecking empire. "Salvaging was once big business in the Keys because countless ships carrying treasure from the New World to Spain were driven on to the surrounding reefs," Bill, the boat captain, told me.

Further along the former railroad, I fed on tarpon at Robbie's marina and visited Lorelei, a typical restaurant, where I ate outside watching the sunset. I passed numerous mangrove islands and creeks and walked along the Seven Mile Bridge, marvelling at its immense architectural beauty with its Roman-style arches surrounded by big sky and sea. Here, the old bridge runs magnificently alongside the new one, now using the rail tracks for its guardrails. I hired a bike to ride over it, joining a throng of cyclists, pedestrians, joggers and roller-bladers.

At the end of the 128-mile island chain is Key West, to where Flagler decided to extend his railway because it was so close to Cuba and the Panama Canal. Despite the project being hailed as madness, Flagler finally rode the first train into a jubilant Key West in 1912. The town, struggling from the loss of its sponge and cigar industries, flourished once more. Cuban pineapples and limes were brought by ship, loaded on to the railway and sent north.

After the 1935 hurricane, Key West was cut off again until it was resurrected as a tourist town: America's own Caribbean island. These days there's a yellow Conch Tour Train which travels around the town. One of the stops, the Flagler Station Overseas Railway Museum, gives another insight into the huge importance of this train. Here, you can watch moving footage of the town going wild as the train first rolled into Key West.

It's hard not to fall in love with the island. Cruise ships stop there, but the souvenir tat is thankfully limited to Duval Street. From there, you can walk away into quiet lanes full of colourful, Victorian-era houses with ornate verandas and shutters. It's leafy and tropical with banyan and kapok trees showing off their colossal buttress roots.

I was staying at Eden House, made up of a couple of renovated conch houses. Hammocks swung in the garden and I had my own porch swing. On the owners' recommendation I hired a kayak one morning and explored the waterways twisting through the mangrove forests of Key West's backcountry. Another day, I visited Nancy Forrester's Secret Garden, where the 74-year-old Nancy keeps parrots abandoned by the pet trade. Sitting with a beautiful scarlet macaw called Lucy on her arm, she explained that they need a lot of affection and mental stimulation. "When I eat out I always take one with me, cycling with them on my handlebar," she said. "I know the parrot-friendly restaurants in town."

On my final day I visited one island not linked by the railroad: the uninhabited Dry Tortugas, 70 miles west of Key West, and the true end of the Keys. I flew in on a small seaplane, looking down on to sharks, stingrays and giant turtles swimming below. The island, now a protected national park, has a fort, which was once a military prison. Now it's a historic monument surrounded by beaches, which you have almost to yourself because only a limited number of people are allowed on the island each day.

As evening came I stood on the fort walls, looking into its centre: wild and overgrown with portia trees and their gnarled trunks. The railway may have changed the Keys but this string of islands still clutches its own strong identity. And on the Keys there are still places, like this, where you can truly escape from it all.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Kate Eshelby flew with American Airlines (0844 499 7300; americanairlines.co.uk), which code-shares with British Airways (0844 493 0787; ba.com) on flights from Heathrow to Miami. Virgin (0844 209 7777; virgin-atlantic.com) flies the same route. American Airlines also has connections from Miami to Key West. Dry Tortugas can be accessed using Key West Seaplane Adventures (001 305 293 9300; keywestseaplanecharters.com)

Staying there

Casa Morada (001 305 664 0044; casamorada.com). Doubles from $299 (£199).

Eden House (001 305 296 6868; edenhouse.com). Doubles from $120 (£80).

Visiting there

Key Largo Bike and Adventure Tours (001 305 395 1551; keylargobike.com) offers daily bike hire from $18 (£12) .

Lazy Dog (001 305 295 9898; lazydog.com) has kayaks from $25 (£17).

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments