In a time before reality TV

Polly Toynbee tuned in to the soap opera scandals that were gripping the nation in ‘Brookside’

19 May 1995

Sociology is nearly dead, killed off by the “society is bunk” school of Thatcherism. Their work ignored by policy-makers, sociologists have retreated into masonic jargon, peppered with cross-references to one another’s work: they have become a kind of ingrowing toenail instead of a source of understanding for us all.

So who has taken their place? Who holds our hand and leads us through the dark maze of society, illuminating how we live, what we think, who we are? It is the soaps. They have become our national parables, the stories through which we debate the way we live now. They are our preachers, with sermons not unlike mystery plays. Once, everyone understood a Bible story reference; now the common culture for expressing human experience is the soap.

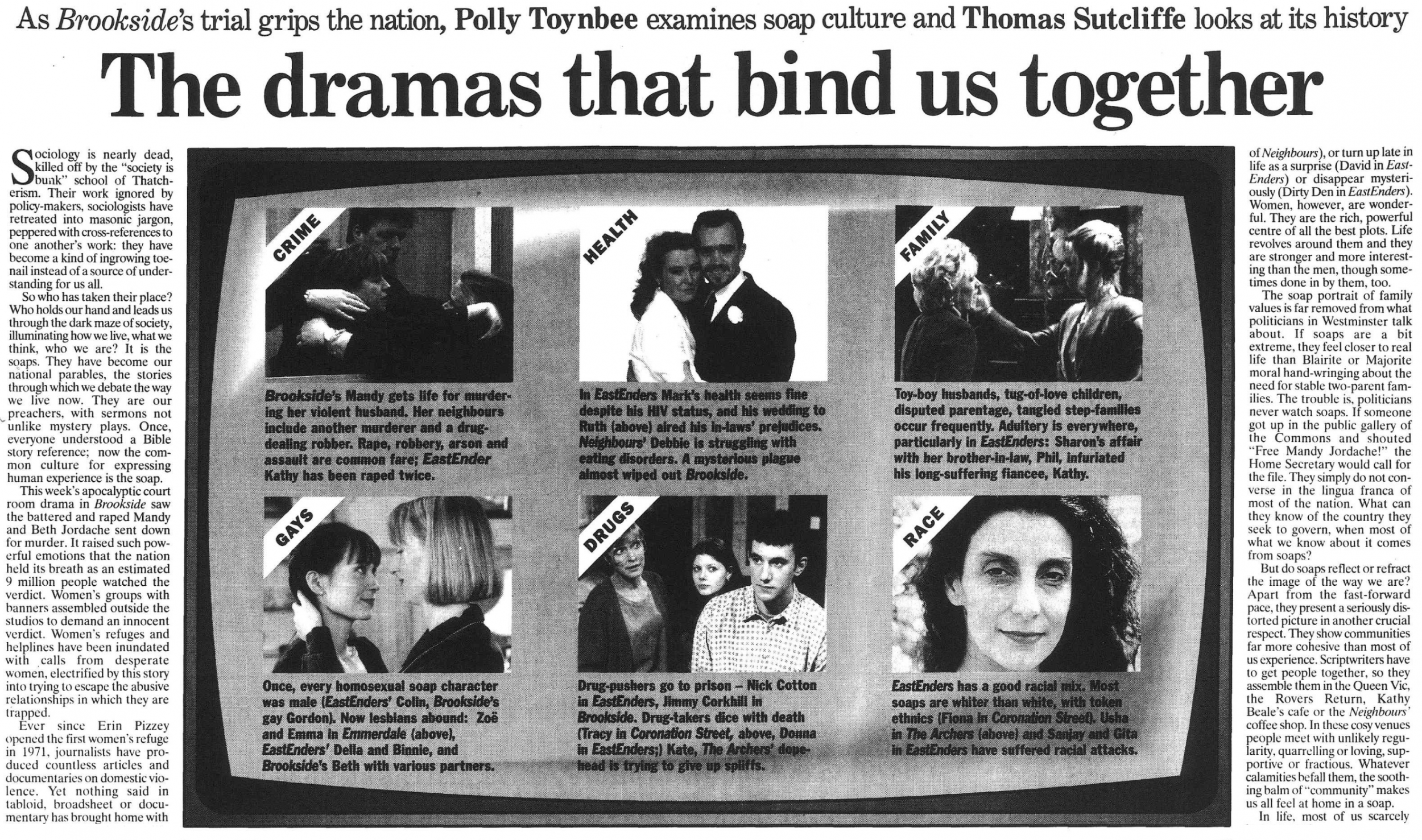

This week’s apocalyptic court room drama in Brookside saw the battered and raped Mandy and Beth Jordache sent down for murder. It raised such powerful emotions that the nation held its breath as an estimated nine million people watched the verdict. Women’s groups with banners assembled outside the studios to demand an innocent verdict. Women’s refuges and helplines have been inundated with calls from desperate women, electrified by this story into trying to escape the abusive relationships in which they are trapped.

Ever since Erin Pizzey opened the first women’s refuge in 1971, journalists have produced countless articles and documentaries on domestic violence. Yet nothing said in tabloid, broadsheet or documentary has brought home with such force the truth about life behind the net curtains. Forget lobbying parliament or public meetings, if you can get your social issue into a soap then you can hit the conscience of the nation at its most vulnerable.

Indeed soaps have become so jam-packed with social problems that there is a danger of them losing their prized gritty aura of realism. If any happy family makes the fatal error of moving into Brookside, for instance, disaster is inevitable. Once you start to examine the plot-lines, the eventfulness of these ‘‘ordinary’’ people’s “ordinary” lives swings between the demented and the seriously pathological.

Interestingly, social issues in soaps are always explicated in a very liberal way. Does that signify that those who watch are more liberal at heart than opinion polls might suggest? Nasty people are racist, black people (who are mainly rather light-skinned) are virtually always nice to the point of being boring. (Usha in The Archers). When a British National Party council candidate stood in EastEnders, around the time when the real-life BNP won an East End seat, not one of the soap’s regulars had any truck with it, and so the candidate lost. The BNP also cropped up in Brookside, only to show the somewhat racist Ron how deeply distasteful real racism is.

Gays are always treated sympathetically. Lesbianism, a statistically rare orientation, currently features in three soaps: Brookside started it with Beth and Margaret, Emmerdale now has Zoe and Emma, while Binnie and Della from EastEnders have just gone off hand in hand to Ibiza, after telling Della’s mother the Truth. (Della’s mother was very understanding and said she’d known all along, mothers not being as stupid as they look.)

For three years Mark of EastEnders has been HIV-positive. But the message is clear: do not be afraid of those with HIV; in fact it’s OK to marry one as they can live long, happy and fruitful lives. He married Ruth last month, and over the years there has been plenty of opportunity for safe- sex talk.

Special-interest groups keep a firm eye on the plot-lines of soaps. Take Coronation Street and the kidney: Tracy Barlow, the adolescent from hell, (lots of those – see Kate Aldridge and Rachel Jordache) took an “E” and went into kidney failure (note that parable, too, given the rarity of Ecstasy-related disasters). She needs a new kidney, her parents’ don’t match, and there is only her young Moroccan stepfather, Samir. Samir is having cold feet, feeling less than 100 per cent generous about giving his kidney to terrible Tracy. Rumour had it that he would die under the knife (his storyline is getting out of hand). Battalions of kidney donor activists, however, have protested that this will deter other donors, so the odds are that Samir will not die. Or not like that anyway.

Families in soaps are wracked with torment, but that’s not unlike life. Most babies in soaps are conceived by accident, virtually all to single mothers, or if married, then soon-to-become single mothers. Fathers usually cause trouble (kidnapping Jack of Neighbours), or turn up late in life as a surprise (David in EastEnders) or disappear mysteriously (Dirty Den in EastEnders). Women, however, are wonderful. They are the rich powerful centre of all the best plots. Life revolves around them and they are stronger and more interesting than the men, though sometimes done in by them, too.

The soap portrait of family values is far removed from what politicians in Westminster talk about. If soaps are a bit extreme, they feel closer to real life than Blairite or Majorite moral hand-wringing about the need for stable two-parent families. The trouble is, politicians never watch soaps. If someone got up in the public gallery of the Commons and shouted “Free Mandy Jordache!” the Home Secretary would call for the file. They simply do not converse in the lingua franca of most of the nation. What can they know of the country they seek to govern, when most of what we know about it comes from soaps?

But do soaps reflect or refract the image of the way we are? Apart from the fast-forward pace, they present a seriously distorted picture in another crucial respect. They show communities far more cohesive than most of us experience. Scriptwriters have to get people together, so they assemble them in the Queen Vic, the Rovers Return, Kathy Beale’s cafe or the Neighbours’ coffee shop. In these cosy venues people meet with unlikely regularity, quarrelling or loving, supportive or fractious. Whatever calamities befall them, the soothing balm of “community” makes us all feel at home in a soap.

In life, most of us scarcely know our neighbours. We live in cities partly in order to choose our friends and escape having them foisted on us by the accident of proximity. We each build a community around us, not geographically but by occupation, interests and affection. That doesn’t stop us enjoying geographical “community” vicariously, but it means that however many real-life issues soaps raise, they are always rooted in an imaginary world that never was.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies