How John Piper and other artists changed the fabric of post-war Britain

As Britain emerged from post-war gloom, bold textiles by respected artists brought optimism – and art – into the home

In Hamburg the Beatles were trying out their new name; in Suffolk, Benjamin Britten revealed his landmark opera A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Frederick Ashton’s new ballet, La Fille mal gardée, delighted audiences at Covent Garden, while Harold Pinter and, in the title role, Donald Pleasence, chilled the spines of the first night audience at The Caretaker.

Penguin was found not guilty of obscenity for publishing Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Like every year, 1960 felt like a pivotal one. With post-war austerity finally past, and a new decade dawning, everything felt possible.

For the forward-looking householder who wanted to express a new optimism in their own home, London had a new, trend-setting port of call: Sanderson House on Berners Street, the headquarters of Arthur Sanderson and Sons, just north of Oxford Street.

Here, floor after floor of vibrant fabric and wallpaper was displayed in its own purpose-built, Modernist setting. After a highly successful decade of importing, commissioning and retailing well-designed textiles, the company celebrated its supremacy in interior design, and its centenary, with the opening of the showroom – which was heavily influenced by buildings such as the Seagram and Lever headquarters in New York.

Sanderson House was the work of the architect Reginald Uren of Slater, Moberly and Uren; having previously designed Peter Jones in Sloane Square and the rebuilt John Lewis on Oxford Street, he was an expert in creating emporia whose endless vistas of consumer goods were wonderlands for a British public that had bleak memories of shortages.

With cheerful disregard for maximising profit and cutting overheads, this new landmark store lavished money and precious retail space on purely beautiful objects – including, most arrestingly, a stained-glass window, still believed to be the largest such in Europe outside a church building, designed by the artist John Piper. (His stained-glass designs would also soon be unveiled at the new Coventry Cathedral. In both cases, the glass itself was made by Patrick Reyntiens, one of the few people from either project alive to this day.)

But Piper’s work did not end with this dazzling display of pure colour and arresting form, a floor-to-ceiling wall of light: shoppers at Sanderson House could for the next few years stroll between lavish samples of abstract prints based on his original work, as well as that of the other leading British artists of the day.

As the Fashion and Design Museum in Bermondsey, south London, also illustrated so evocatively in its marvellous 2014 show Artist Textiles: Picasso to Warhol, mid-20th century European artists took to designing dress and furnishing fabrics as both a refreshing challenge and a useful source of reliable revenue between intermittent sales of their independent work.

At a more ideological level, it was also a way of putting good art within the reach, and into the living rooms and the wardrobes of ordinary people who might be attracted to good design but who lacked either the confidence to splash out on an emerging artist’s one-off piece, or the means to secure work by an established artist, even at a time before art became a commodity like zinc or cocoa.

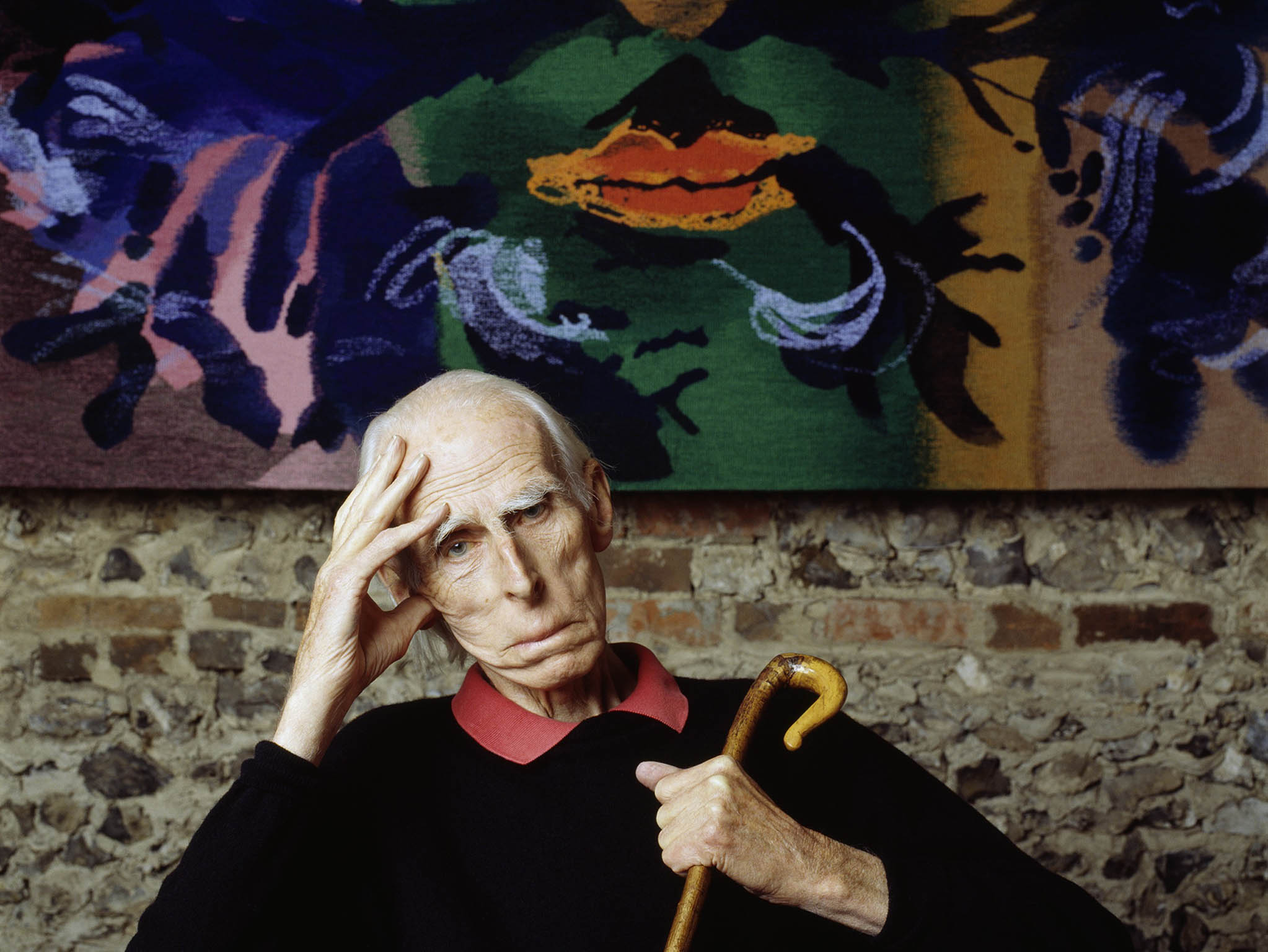

Piper, who was at the height of his powers and celebrity, in part because of his revitalising of British landscape and architectural art in a post-war context, took readily to the demands of designing for a repeat pattern, observes Simon Martin, curator of John Piper: The Fabric of Modernism, opening at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester next month.

In the furnishing fabric called Chiesa della Salute (1959), for example, Piper drew on a stylised drawing of Santa Maria della Salute in Venice, done at a time when the artist was visiting the city for a performance of Britten’s Turn of the Screw at the Teatro la Fenice, with sets by Piper and libretto by his wife, Myfanwy.

Naked performance art, exhibitions and protests

Show all 5Piper understood readily that draped fabric in the form of curtains would cause the design to fragment, and had a natural feeling for the rhythmical columns of the vertical folds, and for using the undulations of the horizontals, so that in Chiesa della Salute, the blue-grey rocking waters at the confluence of the Grand Canal and Giudecca Canal seem to lap at the steps of the great basilica.

For though Piper may be associated with traditional Englishness – with his friend John Betjeman, he championed great churches and other endangered buildings, and co-authored the original Shell County Guides – he was by no means detached from the radical Modernism of artists in the mainland of Europe.

He travelled widely, and in the Limousin region of France he visited the brilliant weavers of Felletin, who realised both Graham Sutherland’s Christ in Majesty for Coventry Cathedral, and Piper’s tapestries for Chichester.

His fabric design Abstract (1955) for the company David Whitehead, drawn from his Abstract painting of 20 years before, recalls the breakthrough Abstract and Concrete exhibition of 1936, the first show of international abstract art in Britain, with its paintings by Jean Hélion, constructions by Naum Gabo and mobiles by Alexander Calder.

“Because of the nature of his imagery, someone could have it in their Modernist house or, equally, in their country cottage.” (It’s true: I recall making up a length of Piper’s hugely successful Stones of Bath into curtains for my parents’ stone-built home in Somerset. An unwarranted measure of teenage bad grace was sewn in; nowadays I would pay to do a job like that.)

Sanderson House still stands, but today it is an achingly, eye-poppingly chic hotel designed by Philippe Starck. The universally youthful staff wear black casual wear, and if you take to a fantastical chair in the yawning reception and are old enough to remember Piper (he died in 1992), you either can’t get up again or find yourself lying down.

It seems a far cry from the Sanderson principle of good, functional design – itself a legacy of William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement. But you can still see the Piper glass wall, if you pick your way into the gloom of the billiard room. And you can imagine the buzz on a Saturday morning in the 1960s – think of any big draper’s now, rare as they are – with room upon room of textiles unfolding in rainbow colours.

Print is back, in a big way. And David Whitehead, one of the companies that produced great fabrics, is now in new hands and shortly to revive some of its mouth-watering designs. Can a new edition of Stones of Bath be far behind?

‘John Piper: The Fabric of Modernism’, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester (pallant.org.uk), 12 Mar to 12 June

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies