Power to the People: Revolution is in the air at the V&A with a survey of protest art from the Seventies to now

Zoe Pilger welcomes one of the most exhilarating, important exhibitions of the year

“Because of my political beliefs and affiliation in the Black Panther Party, I have spent the last 35 years in solitary confinement,” writes Kenny Zulu Whitmore in an open letter to the visitors of Disobedient Objects, a new exhibition that has just opened at the Victoria & Albert Museum. “Torture by any other name is still torture.”

The letter, written this year, is almost unbearable to read. It is one of several objects on display related to the “Angola 3”, a group of three young black prisoners who were forced into solitary confinement in 1972 after they started a chapter of the Black Panther Party in Louisiana State Penitentiary. They wanted to challenge the brutal conditions and racial segregation. The prison is also known as “Angola” after the old plantation site on which it was built.

The Angola 3 case is a disgrace – it is one of the many struggles for justice represented in this rare, important, and powerful exhibition. Robert Hillary King was released in 2001 after 29 years in solitary confinement. Herman Wallace was released last year after 41 years in solitary confinement, just three days before he died of liver cancer at the age of 71. Albert Woodfox remains in solitary confinement. So too does Whitmore, who not part of the original three but became politicised in prison. His letter ends: “Never surrender hope.”

A chrome-plated steel pendant is displayed, made in 2008 by another prisoner on the request of Wallace. It is elegant, stylish, the lettering graceful. But it reads: “Fuck the Law.” There is also a poem by Wallace, written last year: “The louder my voice the deeper they bury me.”

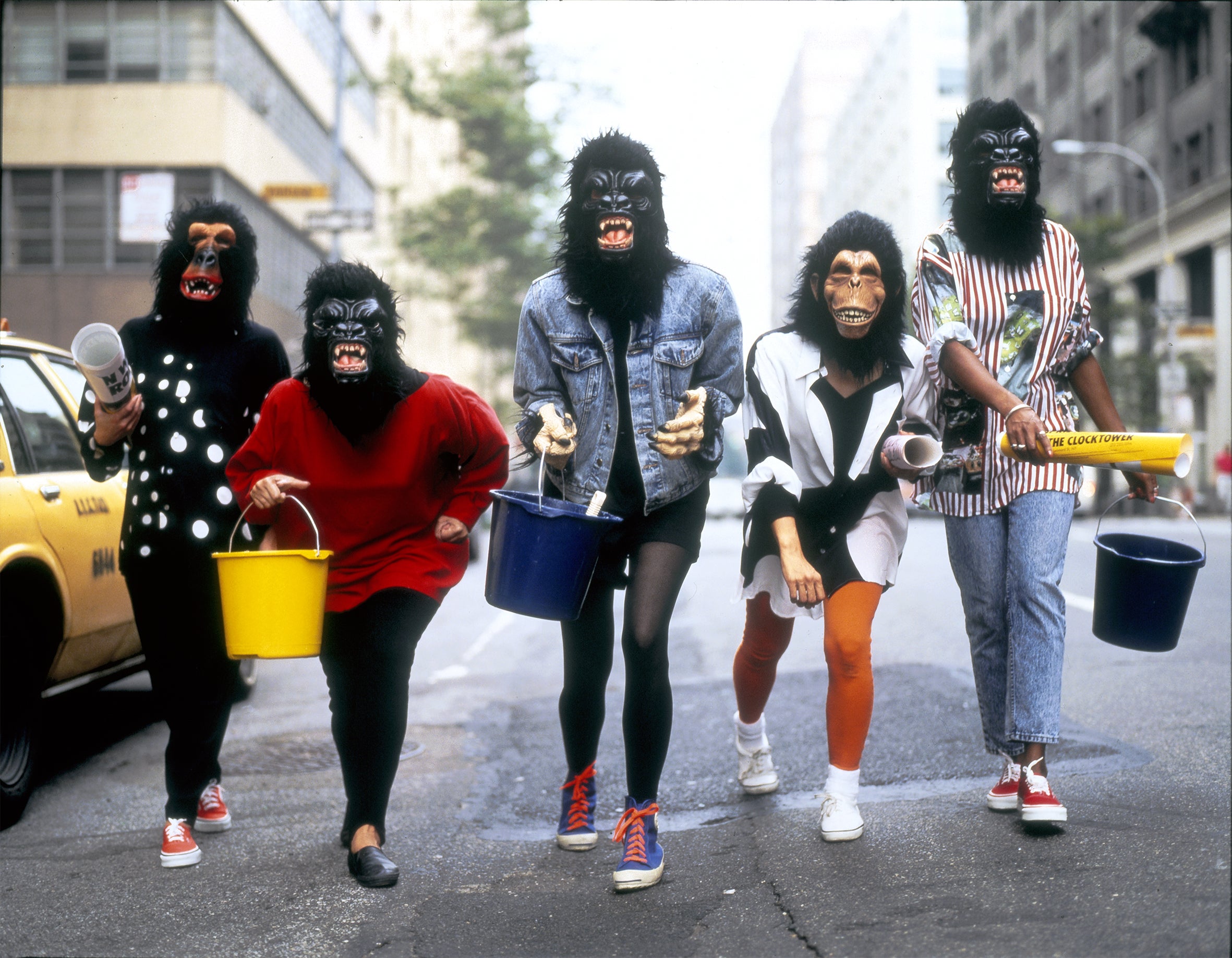

Curated by Catherine Flood and Gavin Grindon, this exhibition is one of the best I’ve seen so far this year. It is about the objects that have played a part in social change, and continue to do so – from a Suffragette teacup to the masked Trini dolls made by the Zapatista movement in Chiapas, Mexico, to anti-apartheid badges to the gorilla masks worn by the art-activist group Guerrilla Girls as part of their protests against the shockingly low number of female artists represented in major galleries in the US.

Far from a nostalgic return to a golden age of 1960s rebellion, this is a call to resist authority right now. A data visualisation map by John Bieler shows that in fact the number of social movements has risen and broadened across the globe since 1979. The exhibition focuses on the past 30 years, and includes many objects associated with the recent Occupy movement.

There are British banknotes stamped with statistics: in 2011, one per cent of the UK population earned £922,433 while 90 per cent earned £12,933. The illegal practice of stamping banknotes with subversive messages as a means of infiltrating the bloodstream of a nation surreptitiously was also used in Burma, where Aung San Suu Kyi’s face was subtly painted on to official notes after she was democratically elected then placed under house arrest in 1990.

The skill of the curators is to bring together objects from disparate movements while telling a coherent story about the fight for basic human rights. At no point does this story seem dogmatic, a criticism often levelled at activist art. Instead, it is a welcome antidote to the complacency of the artworld, which so often derives its value from remaining aloof from society. This is art made by people with much at stake – it is transgressive in the truest sense.

This is most evident in the range of beautiful Chilean arpilleras, textiles appliquéd with covert political messages, made by the mothers of those “disappeared” following the overthrow of the democratically elected Allende government in 1973. The military coup was backed by the US, who wanted Chile to become a laboratory for Milton Friedman’s extreme neoliberal ideas. President Nixon instructed the CIA “to make the economy scream”.

¿Donde Están Nuestros Hijos? (Where Are Our Children?) (c1979) is painful to look at. The anonymous artist was one of the many mothers whose children opposed the Pinochet regime and were tortured and murdered as a result. The arpillera is made of exuberantly coloured fabric stitched on to what appears to be a recycled flour sack, and tells a story of terrible suffering.

Three white doves, symbols of peace, are falling out of a bright blue sky. In the centre are what look like hands or feet, manacled. Below, a mother is on her knees, crying. On either side are two wide open black eyes with demonic red pupils. Their lashes are stiff. They are watching. The arpilleras were dismissed as mere folk art and therefore evaded the censorship of the regime for a period. They provided the women with much needed income, as well as a way to express their grief.

The reverse of the arpillera is also visible. There is a secret pink pocket, which contains a handwritten note: “This represents our children… under the eye of the DINA (political police service).” While the current exhibition of British folk art at Tate Britain politely avoids the issue of class conflict and appears more like a jolly country fête, this exhibition shows with force and clarity how subversive folk art can be.

It is art made by people excluded from elite high culture, often with scant resources, under duress. In the words of the curators, it is art that aims to “out-design” the authorities. The sound of protest drums and singing can be heard throughout the exhibition, which adds to an exhilarating sense of possibility, despite the great tragedy documented.

Surreal and absurdist humour has often been used as a means of protest. There is US TV news footage from 1993 of the Barbie Liberation Organization, in which a rebel Barbie addresses the camera: “We are an international group of children’s toys that are revolting against the companies that made us.” The organisation was in fact started by “a group of concerned parents” protesting against the gender stereotyping of toys. They exchanged the voice-boxes of Barbies with those of G.I Joe toys and then returned them to stores.

Jessica, aged 10, from Albany, New York, is interviewed. She describes how she opened her brand new Barbie to find that it said violent phrases about warfare rather than “I wanna go shopping!” Far from perturbed, she thought it was “hilarious”.

Connections are made across the globe. A photograph of the general strike in Barcelona in 2012 shows giant inflatable cobblestones thrown at police; their size is counterpoised to their weightless. There is also a photograph of a young Palestinian boy from the second intifada in 2000, throwing a stone at military trucks. A Palestinian slingshot is displayed, made out of the tongue of a child’s shoe, dirtied and devastating.

The curators write: “Peaceful disobedience only works when protesters have cultural visibility and the government acknowledges their right to protest. Without this, struggles for freedom can sometimes take other forms.”

Leaflets are provided with instructions of how to make your own tear-gas mask and “book shield” – a large cardboard rectangle painted with the cover design of a famous book. A shield based on the 1962 Penguin edition of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird is displayed; it was used by protesters to fight the closure of New York’s public libraries this year. If the police hit the shields, it would appear a literal attack on learning itself. The Mid-Manhattan Library closure was cancelled in May, and the book shields were cited as a key factor.

In Lee’s novel, Atticus Finch is a white lawyer defending a black man who is wrongfully accused of rape in the racist Deep South. A quote from Finch is printed here, and resonates with the spirit of this wonderful exhibition: “It’s when you know that you are licked before you begin but you begin anyway.”µ

Disobedient Objects, Victoria & Albert Museum, London SW7 (020 7942 2000) to 1 February

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies