When Charlie Chaplin met Pablo Picasso: How a war of egos took place in Paris

Cultural titans, left-wing darlings - but how did Pablo and Charlie get on when they finally met? Their 1952 encounter has inspired a new book by David Caute

Today, Pablo Picasso is rarely out of the news. Tickets must be booked long in advance for the brilliantly refurbished Picasso Museum in Paris, and his works command surreal prices at auction. (Last year, a version of his Women of Algiers set a new world record when it sold at Christie's in New York for $179m.) We hear rather less of Charles Chaplin: the last time his hat and cane were sold at auction, they raised a mere $40,000. But if, in 1952, we had been invited to nominate two world-famous artistic geniuses, still active and thriving, whom we would have liked to find together in the same room, Chaplin and Picasso might well have fitted the bill. But while Chaplin's early, silent films were still shown and adored across the world, Picasso's fame at that time was more problematic.

Already he was sought-after by museums and collectors, but the public regarded him with suspicion or hostility – too modern, too ugly, too in-your-face, as the master of Cubism somersaulted from one baffling style to the next. And while both he and Chaplin had lauded Stalin's Russia, Picasso had recently been condemned by Moscow's academicians and museum curators as "formalistic", "decadent", "bourgeois" and "anti-human". His blood boiled silently, while his celebrated Dove of Peace extended its wings from Moscow to Peking.

Many might assume that Picasso and Chaplin, both born in the 1880s, the "maître" and the "maestro", had little else in common beyond brilliant careers, fame and wealth. Indeed, they could not exchange even an insult in the same language. So what could bring them together? More than might be supposed, and culminating in a celebratory meeting between two inflated egos in Picasso's vast studio in the rue des Grands Augustins, Paris – a collision we shall presently attend, uninvited.

Their two careers had pursued contrasting trajectories. Whereas the supremely self-confident Picasso had remained entire master of his own change of styles during an output spanning five decades, Chaplin by contrast had been confronted by a potentially terminal crisis when silent films such as his The Gold Rush gave way to "talkies". He had to remodel himself as an actor-director in the 1930s – and he did, coming up with such works of genius as Modern Times and The Great Dictator. He had discovered a way of remaining true to himself, always the ridiculous yet captivating clown, while injecting social and political commitment into modern cinema. But what most obviously linked Picasso to Chaplin was an aggressively left-wing outlook, sympathetic to Soviet Russia and scornful of Western "warmongers".

And as such, both were outsiders, heretics.

Having publicly supported the Soviet Union during the war, calling for a second front to take the Hitlerite pressure off the Red Army, Chaplin then backed the abortive US presidential campaign of Henry A Wallace, leader of the Progressive Party. In 1949 he put in a prominent appearance at the fellow-travelling Waldorf Conference in New York, a scene of bitter, Cold-War recriminations. As a result, Chaplin (who had never forfeited his British citizenship) was cordially detested by large swaths of the American public.

Picasso, too, had declined citizenship in his adopted country. When the Nazis occupied Paris in 1940, he stayed put. His native Spain was closed to him by Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War, and by Picasso's famous pictorial lament Guernica, a huge, expressionist canvas of massacre and misery commemorating the fascist air attack on a Republican town. (That the work now hung in New York's Museum of Modern Art was also considered a scandal in the age of Senator Joseph McCarthy.)

Another thing Chaplin and Picasso had in common was short stature combined with Napoleonic energy. Capitalising on his small, slender frame on screen, his stick held by elastic, Chaplin was sensitive about it in public: the women in his life were not allowed to wear high heels. He was also a snob of sorts. His autobiography chokes on the names of all the famous people he had known or met for a handshake. George Bernard Shaw? HG Wells? Of course. Mahatma Gandhi? Einstein and Eisenstein? No problem. Churchill headed the list, followed by Roosevelt.

Chaplin was proud that Hitler himself had banned The Great Dictator (although he seems to have been unaware that Stalin had suppressed the same film just in case the scenes of Nazi mass adulation reminded Soviet audiences that the first man to stop applauding a speech by the Great Helmsman Stalin was a dead man). Chaplin did know, however, that Modern Times had been rejected by Russia, ostensibly because it was weak on socialism (true), but in reality because the film inadvertently confirmed that even demon capitalists provided washrooms and served three-course lunches on trays to their oppressed workers.

Indeed, one illustrious hand was missing from the list of those shaken by Chaplin – Stalin's. Chaplin had never visited the USSR and Stalin had rarely stepped out of it. So there we have a cruel paradox: both Chaplin and Picasso admired the Soviet Union and "Uncle Joe", but their work could not be shown there.

Both the maître and the maestro were notorious womanisers. When they finally met, their mutual passion for young women might well have driven them apart after Picasso took a fancy to Chaplin's fourth American wife Oona O'Neill and threatened to cuckold him – a pledge luckily lost to the language barrier. In puritan America, where the collective voice of women was louder and more litigious, Chaplin's lively sex life had landed him in bitter divorce cases and public opprobrium, culminating in his indictment under the Mann Act, a US federal law that aimed to curb prostitution and "immorality". French public opinion, always more permissive – a man, after all, is a man – had given Picasso an easier ride.

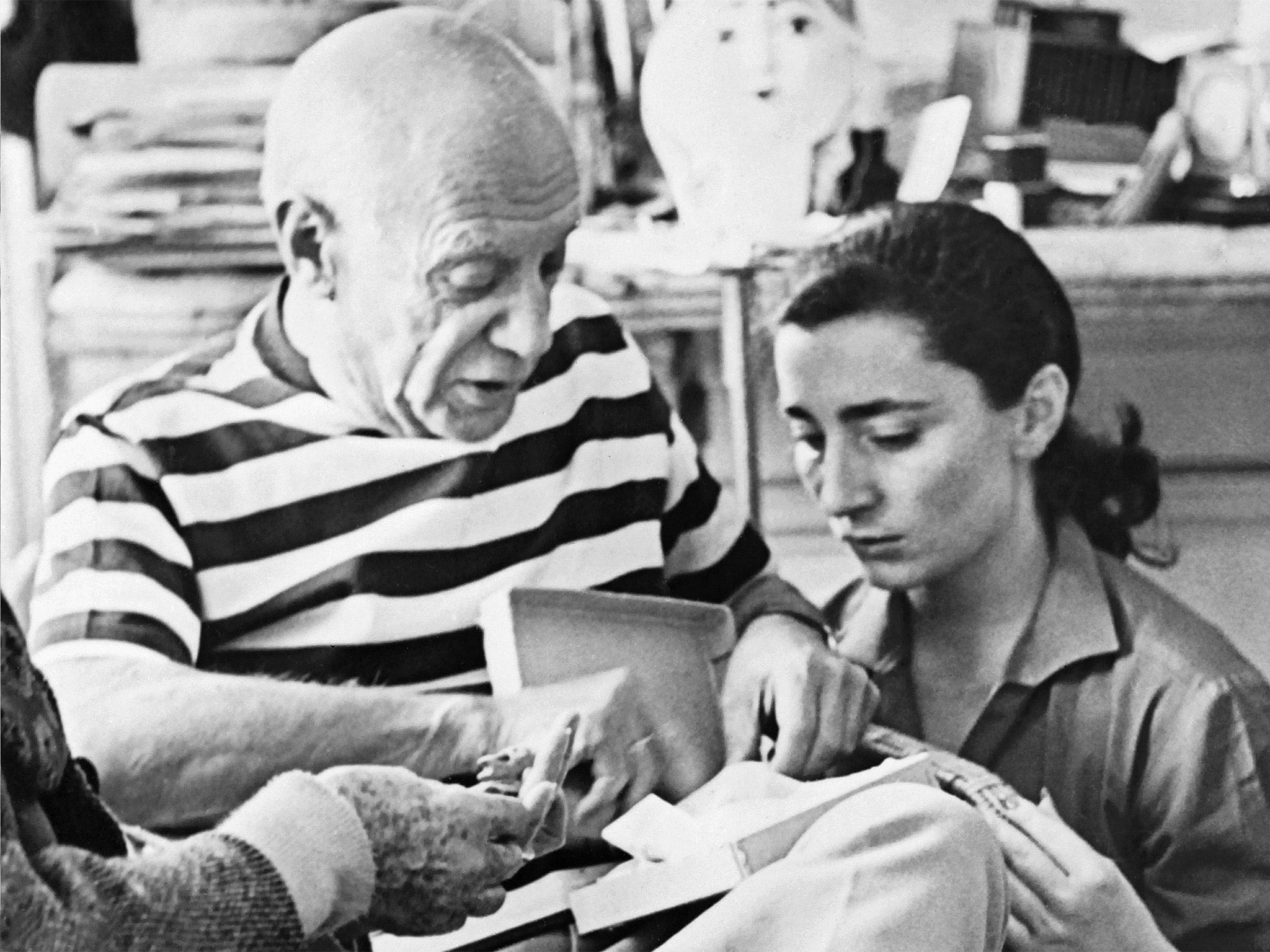

Estranged from his first wife, the Ukrainian-born ballerina Olga Khokhlova, the great artist remained technically married to her from 1918 until her death in 1965, which brought him relief from a lady increasingly inclined to follow him about and harass his mistresses along the seafronts of the South of France. Picasso was a man of many mistresses and muses, including the often-painted Marie Thérèse Walter and the talented photographer-artist Dora Maar, subject of the "weeping woman" portraits. He deserted both when another woman took his fancy. Her name was Françoise Gilot and what he later told her about his rendezvous with Chaplin gives us his version of their meeting. (Chaplin's has yet to be found.)

According to Picasso, Chaplin, who was heading for London with his family in September 1952, was totally focused on the launch and promotion of his new film Limelight, successor to Monsieur Verdoux, a dark comedy more popular with French audiences than American. Set in London in 1914, Limelight almost chokes on pathos and nostalgia. It portrays the decline of Calvero (Chaplin), once a famous stage clown but now a washed-up drunk. Rescuing a despairing young dancer (Claire Bloom) from suicide, he devotes his dwindling energies to reviving her dancing career. Deeply grateful, she is willing to marry the haggard old man, but Calvero altruistically delivers her into the arms of the young composer (Sydney Earl Chaplin, the director's son) whom she loves. The swelling and sobbing theme music is as much a tear-jerker as the story itself.

But Chaplin's popularity was at a low ebb in the US. Persecuted by the FBI, the Catholic War Veterans and the Hearst newspapers, he was now faced with a virtual boycott of the film by the most powerful cinema chains. And his situation, as he headed by sea for London, was worsened by news that US Attorney General James P McGranery, a strong Catholic, had issued a statement threatening to ban Chaplin from returning to America, accusing him of "making statements that would indicate a leering, sneering attitude toward a country whose hospitality has enriched him". Chaplin might never get back to his home in California, his accumulated wealth and his film studio.

At Cherbourg, reporters swarmed aboard the liner; they swarmed again when Chaplin, absent from London for 21 years, moved into his Savoy penthouse suite. The hard voices of the Hearst Press challenged his politics and his sex life. Why had he never applied for American citizenship, they asked? Was he guilty of tax avoidance? What did he have to say about Charles Skouras's decision to ban Limelight from his movie theatres? Had he been invited to visit Russia by Stalin? Naturally, Chaplin hit back, sometimes wittily. Asked whether he had ever committed adultery, he quipped: "An FBI agent visited our home and asked that question. I said no – did he recommend it?"

The next morning he smilingly toured Covent Garden vegetable market in the company of Claire Bloom, currently Juliet at the Old Vic (and tactfully wearing flat shoes), while Cockney porters saluted him. Come the premiere of Limelight in Leicester Square, he stood in the receiving line to greet Princess Margaret, then headed to a dinner at the Mansion House, hosted by the Lord Mayor, where Charlie raised a cheer from the white ties and silk gowns by describing England as "my country". (The next day, The Times pointed out that Mr Chaplin was not inclined to settle for the draconian taxes endured by the rich who chose to reside in "his" country.) And now the Chaplins headed for Paris and Pablo Picasso.

Regarded tolerantly by the French public as, at worst, an exhibitionistic maverick, Picasso's situation was more secure than Chaplin's. Having joined the Communist Party in 1944 after the Liberation of Paris, eight years later he remained the jewel in the Party's cultural crown. In the cause of the Peace Movement, he had even allowed himself to be dragged to a conference in Sheffield. (He later reported that he almost died of cold and didn't find anything he could eat for two days – "It's a mystery how the English take their clothes off long enough to procreate," he told comrades.) For the newspaper l'Humanité he produced a touching sketch of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, imprisoned then executed for atomic espionage. He also came up with a strangely displaced canvas, Massacre in Korea, depicting semi-medieval robots mowing down women and children.

Picasso's misgivings about Soviet Russia were jealously kept under the carpet by the French Party. But he could not forget the relentless denigration of his work – "dismembering humanity" – in the Soviet press. The Russians had locked away in cellars their rich collection of Picasso's early works purchased before the revolution by the wealthy collectors Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov. (Jean-Paul Sartre ironically described "the nausea of the Soviet boa constrictor, unable to keep down or vomit up the enormous Picasso".) That was why, according to the histories and biographies, Picasso rejected all invitations to visit Moscow in the cause of "peace". Even in 1956, when the Pushkin Museum finally staged a retrospective of his early work – hugely attended by a curiosity-driven Soviet pubic enjoying the post-Stalin "thaw" – he failed to turn up.

But back to Chaplin: here he is arriving in Paris for the French premiere of Limelight, celebrated by dinner with President Auriol, the award of the Legion d'Honneur and a grand visit to the Opera. The Left rallies: Chaplin is not to be abducted by the reactionary state. The leading Communist writer Louis Aragon, fluent in English, arranges a first meeting between Chaplin and Picasso at a dinner attended by Sartre. Chaplin tells Picasso, "I am a great fan of yours", an excusable exaggeration.

From this emerges the invitation to Picasso's studio, so Chaplin brings Oona by limousine to the rue des Grands Augustins. Knowing no more of the French language than Chaplin, she is beautiful, radiant, affable. Le tout Paris, invited or not, presses into the capacious studio with its stacks of canvases. Aragon explains to Chaplin how much Picasso admires his films, notably the rapid, deft way that the villainous Monsieur Verdoux flips through the pages of a telephone directory in search of new female victims – and the way he counts their money after disposing of them. Meanwhile, Aragon's Russian-born wife, the writer Elsa Triolet, explains to Oona how Pablo had tried to count his own money as rapidly as Monsieur Verdoux: "He made more and more mistakes and there were more recounts."

Oona is puzzled: doesn't Picasso know about banks? Triolet replies: "Pablo has always carried around with him an old red-leather trunk from Hermès in which he keeps five or six million francs. He calls it 'cigarette money'." Oona wonders whether he should smoke so much, while Chaplin beams genially: "As Henry Ford once remarked to me, a man who knows how much he's worth isn't worth much."

Carefully kept from the Chaplins by Aragon and Triolet is the fact that Picasso, taken to view Limelight, had come away distempered. "I don't care for the maudlin, sentimentalising side of Charlot [Charlie]," he had complained on leaving the cinema. "That's for shop girls. It's hand-me-down threadbare romanticism and it's just bad literature."

In fact, Picasso was incensed to witness Chaplin's ageing Calvero sacrificing himself sexually by handing over the heroine to a younger man. Picasso says he would rather let a beautiful young woman die than see her happy with someone else. (His own struggle with virility is relentless.) The Chaplins, meanwhile, merely peck at the culinary delicacies on offer – are these snails or something?

The packed room falls silent as Picasso instructs Aragon to convey to Charlot the profound thought that both he and Chaplin are masters of the silent gesture, "no description, no analysis, no words". Chaplin nods, bemused – Limelight is fully scripted (inevitably by Chaplin) and Picasso may be indicating an adverse opinion about Chaplin's work since the silent cinema. Chaplin responds, to general delight, by lifting the hat he is not wearing, wriggling his eyebrows and twiddling an invisible moustache. He then launches into the dance with the rolls from the New Year's Eve sequence in The Gold Rush. Huge applause. Picasso beams with delight.

Later, he and Charlot will closet themselves alone in the bathroom to practice the clown's inimitable shaving routine. And when they emerge, Oona – not so cautious about the flowing wine as about the snails – now stands herself back-to-back with Charlie, bends her knees, and giggles: "See? Charlie's taller."

"Moi aussi! I try!" roars Picasso, aflame. Oona obliges him, by no means coyly, again bending at the knee and maybe (accounts differ) playfully butting his bottom.

Much aroused, Picasso turns to Aragon. "Tell Charlot I wouldn't want to insult him by not desiring his wife. Tell him only a very wealthy friend is worth cuckolding." But this does not reach Chaplin. Aragon has abruptly forgotten his English.

The Chaplins departed for Rome and London with the McGranery cloud darkening their lives: Charlie's acceptance of permanent exile from America meant sending Oona home to California on a desperate mission to recover and transfer what may be called the crown jewels, not forgetting to close the family mansion and dismiss the faithful servants. This she bravely did.

The histories and biographies inform us that the Chaplins then headed for Switzerland to find a mansion suitable for a long exile. But a historian I know well believes they first spent two weeks in Moscow, along with Picasso, Aragon and Triolet as part of the Stalin birthday celebrations. According to my newly discovered evidence, the expedition turned into a highly dramatic, multiple disaster; but into this story I do not venture here. Some may unwisely call it "counter-factual" or even mere fiction

David Caute's novel 'Doubles' (Totterdown Books, £14.99) is out now and available from The Independent Book Shop

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies