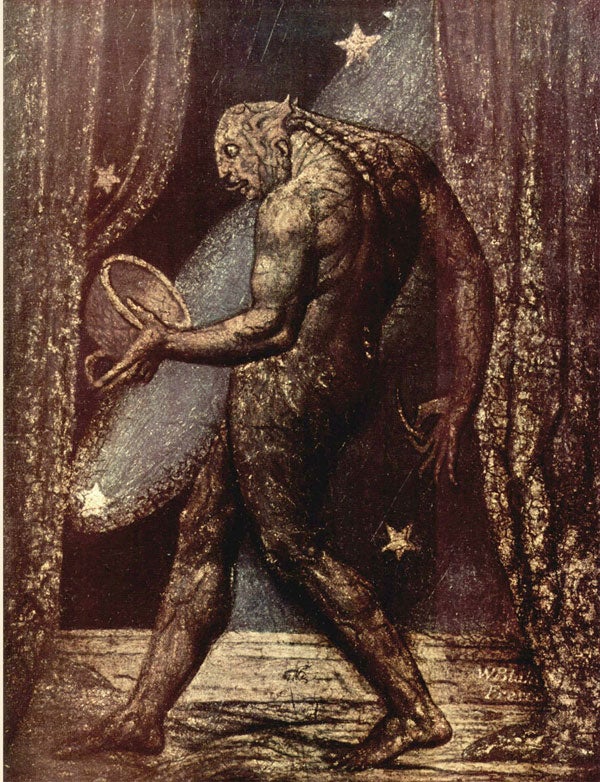

Great Works: The Ghost of a Flea (c.1819-20) (21.4cm x 16.2cm), William Blake

Tate, London

Blake's words and images – and especially when they form a part of one or another of the many illustrated Prophetic Books – often seem to arrive as if from nowhere. Well, nowhere within reach of our immediate understanding. Angels and demonic beings loop around his words, transporting them goodness knows where. We are never a party to his visions. How could we have been? Nor even was his wife and faithful, life-long collaborator, Catherine. We can never know who or what spoke to him, or dictated to him the words or the images that he was said to have transcribed. We can only assume that he struggled to transcribe them faithfully, as far as he was able. It is for this reason that we often seem to be looking at the world of Blake through a glass darkly, in the words of St Paul.

What we do know is that the images are often violently at odds with the common world in which we move, breathe and have our being. They live in some strange, set-apart space of seemingly endless visual exaltation. And yet this is also not quite so. We do see, in part at least, where they come from. There is a great deal of religion in his work, but it seems to be the religion of a wild apostate from the core dogmas of Christianity – even allowing for the influence of Swedenborgianism. Jesus keeps some very odd company. There is also politics, but even some of Blake's politicians take on the aura of the supernatural. And what of insects? Does he have time for those too? Well, yes. All things, great and small, seemed to matter equally to him if we are to believe those great words of his in a poem called "Auguries of Innocence": 'To see a world in a grain of sand... Hold infinity in the palm of your hand...' In Blake's world, the smallest things can be huge, and the loftiest, puny. It all depends upon their imaginative and emotional heft.

Take this image of a flea for example, so tonally dark, but also magnificently enriched by gold across the dark mahogany surface. What kind of a flea is this? The point of a flea is that it is peskily small, and, from a physical point of view, utterly insignificant. As John Donne once wrote to his lover, mockingly, and in a characteristically unholy mood: "Mark but this flea, and mark in this /How little that which thou deniest me is..." A flea is utterly risible on account of its size, and, being small, it is therefore a thing of almost no consequence. It exists only to torment us.

This flea, on the other hand, looks quite the opposite. This self-vaunting monster looks like a creature of some moment, not to be easily cast aside or screwed into nothingness beneath a careful thumb. Fully embodied, it is striding the boards of what almost looks like a stage set (see those magical, drape-like trees – if that is what they are - to left and to right of it) – stepping out like a great Shakespearean actor. Its look is violently purposeful. Its huge ear sweeps back and up like an elaborate architectural feature. Its fingers are long and violently flexing. It stares long and long into the rimmed, bucket-like acorn cup that it is gingerly carrying in its left hand, as if summoning the future. In its right, it holds a nasty curling thorn. It has all the tremendous muscular allure of a male nude by Michelangelo. Malignity writ large then. Yes, it seems to have all heaven in its tow: all those shooting stars, fresh snatched from some tree in the children's nursery, look as if they are dancing attendance upon it as they fizz and roar at its back. It looks like some magician that is about to yank a trick out of its acorn cup. In short, it has a wonderful, commanding presence. The natural world seems to pivot about it. This flea is determined to get somewhere.

But how does this creature fit into the scheme of things? And can it really have been studied and anatomised by the eye of the artist? Oh yes. According to Blake's friend, John Varley, this was a flea which Blake himself saw – in a vision, of course. Here is what Varley wrote of the occasion:

"I felt convinced by his mode of proceeding, that he had a real image before him, for he left off, and began on another part of the paper, to make a separate drawing of the mouth of the Flea, which the spirit having opened, he was prevented from proceeding with the first sketch, till he had closed it. During the time occupied in completing the drawing, the Flea told him that all fleas were inhabited by the souls of such men, as were by nature blood-thirsty to excess." Not only a flea to be painted then. Also a flea to be listened to, with rapt attention.

That drawing of the mouth of the flea is also in the Tate's collection.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

William Blake (1757-1827) was one of the greatest artists and poets of the English Romantic tradition. Almost entirely neglected during his lifetime and long after, he held just one exhibition (above his brother's shop), which was commonly regarded by the critics as a resounding failure. His poetry is just as important as his paintings, drawings and prints, though his 'Prophetic Books' often descend to breathtaking depths of obscurity. He claimed to be dictated to by angelic beings, and he recorded their presences for posterity to contemplate.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies