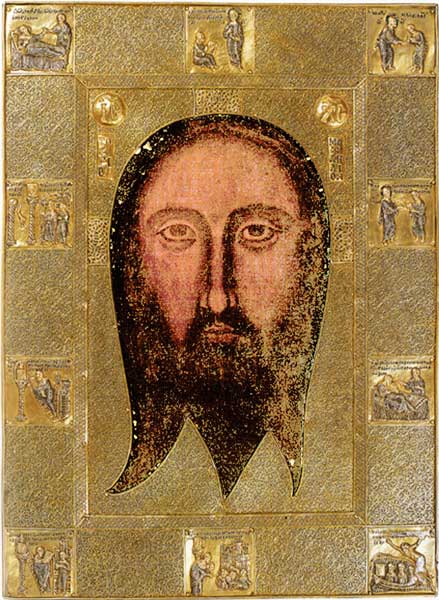

Great works: The Holy Face (14th century), Anon

Church of St Bartholomew of the Armenians, Genoa

A mask reveals. When a face is partially hidden, it becomes a show. A full and simple disclosure is no disclosure at all. But when something is obscured, it is like a curtained theatre. The burqa, the balaclava, the Venetian masquerade bauta, all these coverings are also forms of openings. The eyes or the mouth are a spectacle.

And this can be any frame, applied to any image, just so long as we feel that something extends further beyond the frame, something out of view, off picture. It's an aperture, a peepshow, a keyhole, a visor. Our sight is in some way blocked, and therefore what we can see is particularly focused.

Or that's one effect of a frame. But it can perform a different function. It can be seen as a surrounding container. It is like a rim, an encasement, a mount, a setting for a jewel. And now the object doesn't spread outside the limits of the frame, partly glimpsed and partly masked. It is held entirely within the edges of its close embrace. It's an image outlined and shaped by its stencil. It is enclosed and moulded.

So there are these opposing framing effects. One is an aperture. One is an enclosure. One is viewed through; the other is held tight. Each one has its distinct power. One is a mysterious revelation, something lurking behind the frame. And one is a defining template, something grasped within the frame. Both effects can work together.

Look at the Holy Face of Genoa. It is already a magical image, of course. It is known as a "Mandylion", a hand towel, believed to carry the face of Jesus. It is one of those pictures called "acheiropoieton": miraculously not made by human hands. But it's not in fact a "Veronica", where Jesus's likeness was printed in his sweat on a cloth, which St Veronica pressed on to his face, as he was carrying his cross to his crucifixion. This Holy Face is derived from an even less authentic legend (if that's possible), though if the legend were true, it would get even closer to Jesus's body.

For this is an image made of and by Jesus himself. The pious story tells that Abgar, King of Edessa (Urfa, in modern Turkey) sent a message to Jesus, asking to be cured by letter. By return of post, Jesus went one better. "The saviour then washed his face in water, wiped off the moisture that was left on the towel that was given to him, and in some divine and inexpressible manner had his own likeness impressed on it." It's a unique self-portrait by God himself.

The actual dating of this cloth, with its compassionate, morose and hypnotic likeness, is unknown. (There are two other versions.) This one was donated to Genoa by a Byzantine Emperor in the 14th century, when it acquired its outer silver-gilt frame with a head-shaped cut-out. It bears 10 embossed scenes, telling the story around the edge of its rectangle. It is a protective armour for this vulnerable cloth. It is an adornment of this precious icon.

But there is more than that in the frame, and also more in the magical look of this transfixing face. Or rather, there is a crucial relationship between this frame and this face, and their twofold power. Both an aperture and an enclosure are at work.

The Holy Face is masked. It is peeping and peering out of a world that is behind and beyond this keyhole. Its gaze focuses our gaze, its eyes are the centre of our attention, and the rest of it fades out into darkness and into the unknown. We can't tell what more of it there may be, but this face is looking at us from an unseen realm.

Equally, the Holy Face is stencilled. It is made into a defined and compact entity. Far from being an unformed face, it can be seen as a visibly stamped contour. This head, with its low brow, and its three curled points of hair and beard, and nothing else, no neck or shoulders, becomes a strange and self-sufficient thing. It resembles some kind of polyp or jellyfish. It is floating within this frame.

So there are two ways in which Jesus's presence is framed. One way, it is almost a pure gaze, looming, lurking, appearing out of nowhere. The other way, it's a face that is sharply shaped, a tangible object, but shaped like a living creature, held and encased within a hard carapace. Two realities: a look; a body.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies