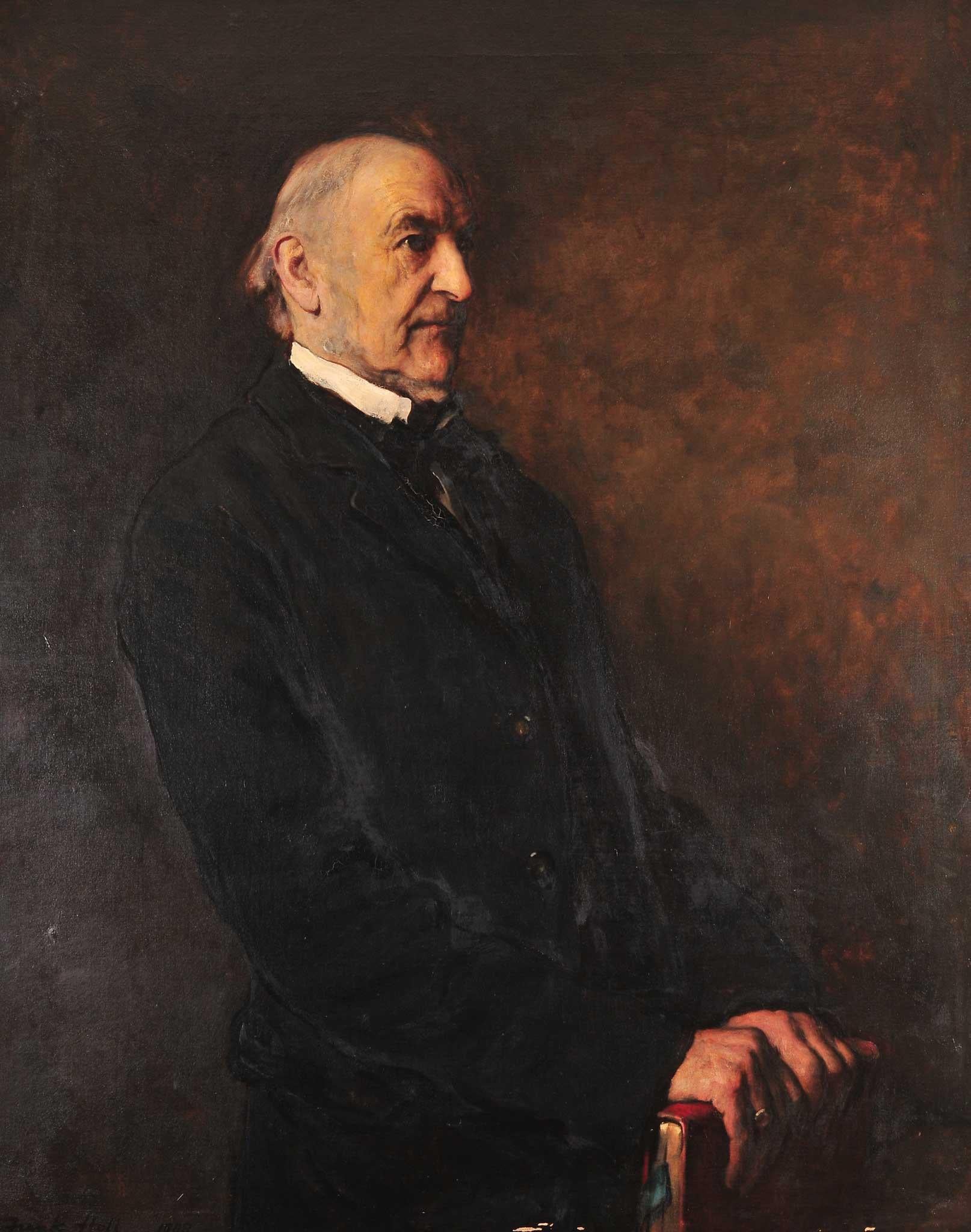

Great works: William Ewart Gladstone (1887-8) by Frank Holl

Private collection

Frank who? Yes, the name of this Victorian artist is little known. More's the pity. He – like many another – has fallen under a curse. In his early creative years (he died, tragically young, at the age of 43), he was a narrative realist, a painter of scenes of sentiment that occasionally spilled over into sentimentality. He painted the distress of Welsh fishwives, the citizen wrongfully banged up in Newgate, the foundling from the street, coddled in the arms of the compassionate peeler.

He possessed a strong sense of social injustice, so he could readily be accused of pointing a moral, adorning a tale. Many of those who came after – well, let us call them, with the broadest of broad brushes, the aesthetic school –hated that sort of thing, and that hatred has infected the attitudes of many artists throughout the 20th century, and even into our own day. Subject matter! That is not what the Moderns are after, we can hear them all saying...

You could argue that Whistler and his aftermath were to blame. Whistler was striving for pictorial effects, objectivity gently sliding in the direction of subjectivity. The subject matter became secondary to the idea of the pursuit of the authentic new manner. Most of Victorian art – the stuff that Henry Tate bought for his new gallery – was consigned to the dustbin. Only now are we beginning to dust it off, to assess for ourselves quite how good these artists had been as painters, and to wonder at our own deeply ingrained prejudices, which have probably included a lingering distaste at the idea of Empire.

In the last decade of his life, Frank Holl changed direction, dramatically. He took up portraiture. Portrait painters were much in demand in the last quarter of the 19th century. They were paid very well for their labours. Holl began to capture the likenesses of the grand old men of the moment: titans of industry, bishops, sea captains, civil servants and, almost last of all, the great and near indomitable William Ewart Gladstone, four times Prime Minster and vigorous tree-feller (it was his favourite outdoors pastime on his estate at Hawarden) well into his eighties.

Here is Gladstone posing, ramrod straight, in his library at Hawarden (though the indeterminate painting of the ground, utterly lacking in detail, turns it into everywhere and nowhere), ever mindful of the pose that he is absolutely determine to strike. This is the helmsman, luminary, leader of men. Two large, knuckly hands batten down on a gilt-edged, leather-bound book with a handsome blue silk bookmark as if it were the back of a chair. Holl has painted the clothing in a fairly cursory fashion – he was no Bronzino or Vermeer, lovingly lingering over fabrics. Least of all is the attention given to the white collar. It is painted almost crudely dismissively.

Most of our attention is drawn to the face, that head, the body's crowning triumph. The nose is like a great prow, pushing into futurity. There is nothing restful or reposeful about this pose. It is almost chillingly steely. This is a mind in full flight, bearing down on its detractors. The air of forcefulness seems almost willed – perhaps that is almost bound to be the case when you are a man in your ninth decade.

Holl found the task of making this portrait utterly exhausting. It was commissioned by rich aristocrats. It was his task to measure up to the expectations of sponsor, sitter and that wider world of soon-to-be-admiring-or-disparaging onlookers. His agonies are recorded in his notebooks. Gladstone was mightily impressed. The young man – barely more than half Gladstone's age – had passed the test. Holl died soon after.

Four years later Gladstone, still flaying with his gladiatorial axe, became Prime Minister for a fourth time.

The portrait is currently on display at the Watts Gallery, Compton, Surrey (01483 810235), in Emerging from the Shadows, the first ever retrospective of Holl's work, which continues until 3 November

About the artist: Frank Holl (1845-1888)

Frank Holl was born in London into a family of engravers. By the 1880s, having been elected a Royal Academician, he was a celebrated portraitist, and was living beyond his means in buildings designed by Norman Shaw, which consisted of a house and studio in Hampstead and a country retreat in Surrey. He may have died of sheer exhaustion – his friend, the painter John Everett Millais, once wrote of Holl's "killing portraits". He was married with four daughters, one of whom wrote his biography.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies