Chris Ofili, Tate Britain, London<br/>Afro Modern: Journeys Through the Black Atlantic, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool

A Chris Ofili retrospective traces the artist’s journey from anger to serenity

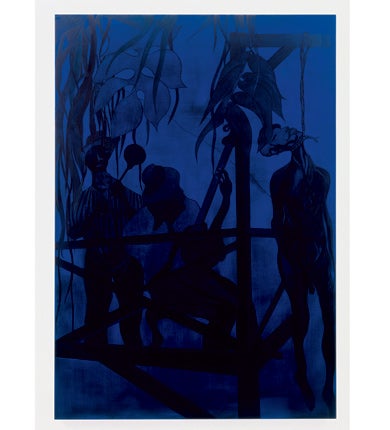

Chris Ofili’s Iscariot Blues is the most beautiful picture made in this short century, and something more besides. The canvas, painted three years ago and in a Chris Ofili retrospective at Tate Britain, also represents a change of gear – a brave thing for any artist, but particularly for one whose style has been as recognisable (and as successful – note the 1998 Turner Prize, the British Pavilion at the 2003 Venice Biennale, etc) as Ofili’s.

The first thing you notice about Iscariot Blues is that its surface is flat, shorn of the dots of raised acrylic that covered works such as No Woman, No Cry (1998). The second is that it belongs to a suite of paintings called Blue Rider, an echo of Kandinsky’s Blaue Reiter, now a century old. In an unexpected way, Ofili seems to be reliving 20th-century modernism backwards.

No Woman, No Cry and the elephant dung paintings always struck me as angry works, reclaiming an African primitivism [sic] stolen by such imperialists of the eye as Picasso. Ofili’s was not the easy negritude of Picasso’s époque nègre: it was in-your-face, like-it-or-lump-it blackness characterised by rap, and by pictures with titles such as Seven Bitches Tossing Their Pussies Before the Divine Dung; by the split beaver of an Afronude watercolour, the soup-plate nipples of Blossom. You want African? – you’ve got it, they said.

Now, like Picasso’s, Ofili’s Black Period has given way to a Blue one – to a suite of pictures whose almost monochrome palette turns against the reds and greens and earth tones of his earlier work, which seem to find a form of serenity. If we’re being historicist about Ofili – and I think we should, at least in part – then his counter-colonising of Western art goes further.

For the past five years, the artist has lived and worked in Trinidad, his answer to Gauguin’s Tahiti. Whether this echo is conscious doesn’t really matter. The idea of a black British painter of African descent exploring the culture of an ex-British West Indian colony suggests all kinds of tensions, political history being played out art historically.

Iscariot Blues shows a bobolee, an effigy of Judas, hung, in my own Trinidadian childhood, from lamp posts on Good Friday and beaten by villagers. It is a complex and haunting image, touched with the same oneiric feel as Ofili’s fellow Trinidad painter, Peter Doig. Its blue depth and slightly iridescent surface by turns call you in and keep you out, like looking through dark trees or into dark water. It has the directness of great painting, and the unknowability.

A picture you might have expected to find in Ofili’s Tate Britain show was his Double Captain Shit and the Legend of the Black Stars (1997), although you’ll have to go to Tate Liverpool to see it. And you should: Afro Modern, the show in which Captain Shit makes his appearance, is excellent. Working with the historian Paul Gilroy’s idea of the Black Atlantic – a transoceanic criss-crossing of African cultures since the diaspora – Afro Modern examines the experience of black art and artists over the past century or so.

Much of the work is, and is intended to be, hard to look at. Edward Burra's Harlem (1934) and Palmer Hayden's Midsummer Night in Harlem (1936), hung side by side, have the embarrassing, coon-show feel of The Black and White Minstrel Show. What makes this more tragic is that Hayden was himself African-American: so complete was the white annexation of "primitivism" that black artists, too, bought into it.

Succeeding rooms explore various strategies for coping with this problem, for finding an art that dealt with enslavement without being enslaved to it. These ranged from the Africanisation of European Modernism proposed by the Natural Synthesis artists in 1960s Nigeria to the dissident in-your-face-ness of Jean-Michel Basquiat. And to Ofili, whose Captain Shit appears in a final room called Post-Modern to Post-Black.

This is, in a good way, the most difficult room of all. The artists represented in it – alongside Ofili are the likes of African-Americans Ellen Gallagher and Kara Walker – are "adamant about not being labelled "black'" while still being "deeply involved in redefining complex notions of blackness". While all this may be true, it would be foolish to argue that any non-black artist could bring the same intensity to the task; that art, in the current world, can ever be race-neutral. To divorce Chris Ofili from the history told by Afro Modern – to see him simply as a Britartist, say – is to deny the anger of those early paintings, the sarcasm that underlies them. Equally, to see those same works as "black art" is to underplay all the other things that they are and do.

Just as the sheen of Iscariot Blues's surface hides its blue depths, so the beaded surfaces of Blossom and the rest tell a different story from the macho- rapper titles and images. They are, in their craftedness, oddly womanly, and they are extraordinarily beautiful. See both shows if you can.

Next Week:

Charles Darwent visits Tate Modern's 'Van Doesburg and the International Avant-Garde', dedicated to the Dutch founder of De Stijl

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies