Visual art review: Mexico: A Revolution in Art, 1910-1914 - so where is the writing on the wall?

An exhibition of work from post-revolutionary Mexico is structurally unsound: it lacks murals, the people’s medium

Just to annoy, I’m going to start this review of the Royal Academy’s Mexico: A Revolution in Art with a work that isn’t in the show – that isn’t anywhere, in fact, it having been destroyed soon after it was made in 1934.

Two years earlier, John D Rockefeller had commissioned the Mexican artist Diego Rivera to paint a mural for the new Rockefeller Center in Manhattan. Called Man at the Crossroads, its subject would be the 20th century’s great leap forward. In the Marxist Rivera’s view, this naturally meant including a portrait of the hero of that leap, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin.

When Man at the Crossroads was unveiled, there were gasps of capitalist rage. Rivera’s good-natured offer to balance the offending portrait with another of Abraham Lincoln was refused. He, in turn, refused to paint Lenin over. There could only be one outcome. At midnight, a team of Rockefeller’s builders marched on the Center and took pickaxes to Rivera’s wall. Lenin cut down by the workers: the image is unforgettable.

I begin with this non-existent work because its absence is central to the RA’s exhibition. Man at the Crossroads isn’t in the show because it was destroyed, but wouldn’t have been anyway because (a) it was 63 feet long, and (b) it was a mural, and so stuck to a wall.

Rivera later painted a scaled-down version back home in Mexico, but that isn’t here, either, for the same reasons. Nor are murals by either of the two other of los tres grandes – the Big Three – José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Since mural painting was central to Mexican art in the decades after the 1910 Revolution – the period covered by this show – it is a grave lack, like an ice-cream cone with no ice-cream.

True, there are works on canvas by all three of los tres, including Rivera’s Dance in Tehuantepec and Orozco’s Barricade. But although these give an idea of style and subject, they are, in a sense, worse than nothing.

Paintings on canvas are made for private consumption, murals belong to everyone: that, for Marxist artists, was their point. Pictures could speak to an illiterate peasantry, and there was an indigenous Mesoamerican history of mural painting as well. This mattered to people like Rivera. Indigenous (brown) people remained at the bottom of Mexican society, kept there by (white) descendants of the Spaniards who had enslaved them: thus the Mexican Revolution. To represent the muralists by work other than their murals is to paint a badly misleading picture of them.

This is so fundamental a flaw that Mexico: A Revolution in Art was never really going to recover from it. You can show the muralists well – the Hayward’s The Murals of Diego Rivera did just that in 1987 – but it calls for a lot of contextualisation and a lot of space. This exhibition, squashed into the Sackler Galleries, has neither. How do you approach a subject as vast (and as vastly important) as post-revolutionary Mexican art in 120 small works, more than half of them photographs? The answer, if you are wise, is that you do not.

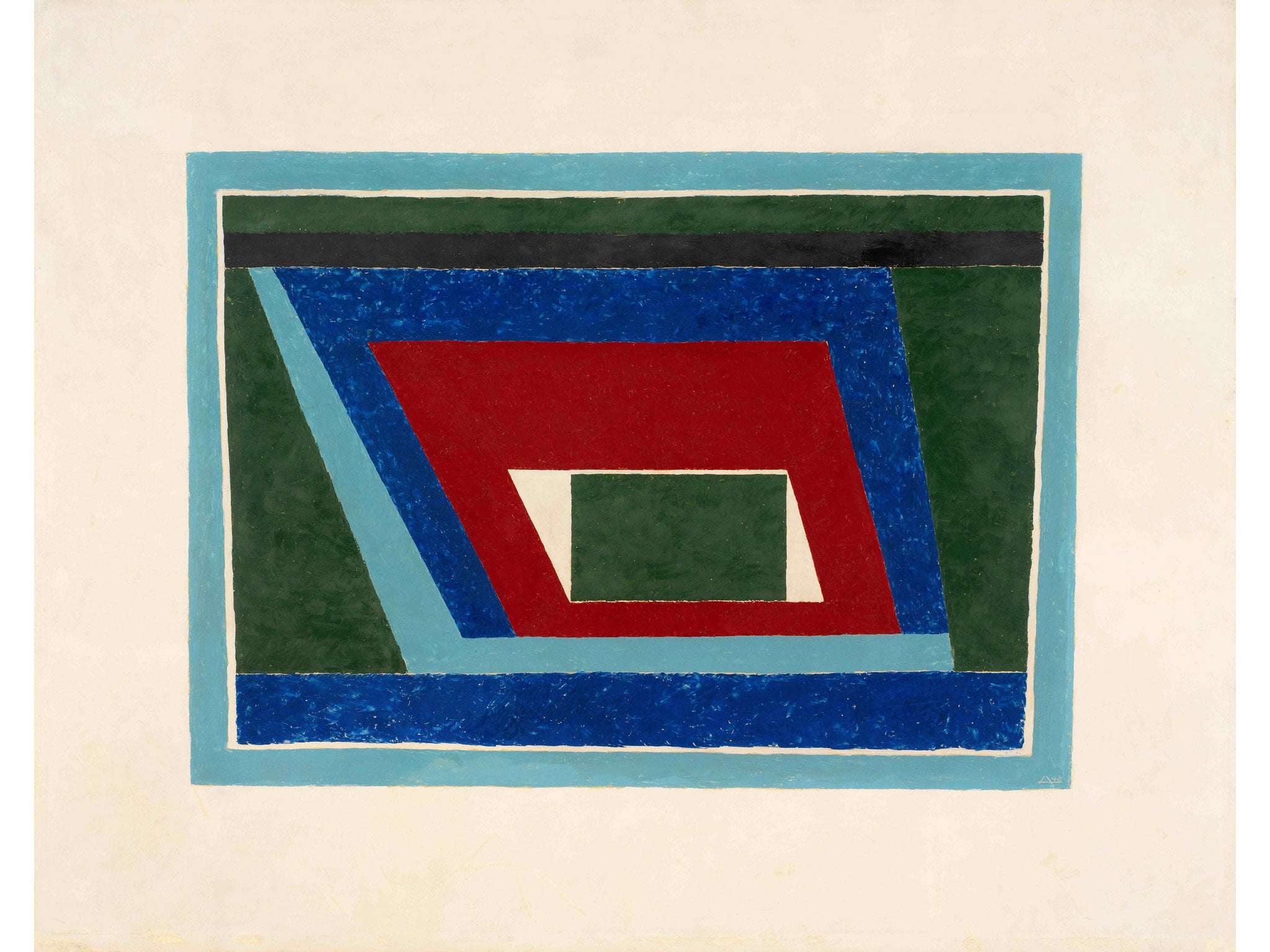

This is not to say that there aren’t good things in Mexico: A Revolution in Art, merely not enough of them. As if its ambitions weren’t outsize enough, the show also includes non-Mexican artists who worked in the country at the time. This in itself would have made an interesting show in a larger gallery – an extraordinary range of foreigners were swept along by Mexico’s revolution, from the English figurative painter Edward Burra, to the ex-Bauhaus abstractionist, Josef Albers. Albers’s Mantic is one of the most intriguing images in the exhibition, revealing an unsuspected debt of his work to pre-Columbian geometry. Burra, in quite a different way, tries to out-local the locals, painting suggestible-looking male peons in a cod-Mexican style.

As in the story of Rivera’s Rockefeller mural, though, the Mexicans find themselves caught between the USSR and the USA. If their political ambitions came from the former, their means of expressing them came from the latter. Gerardo Murillo (aka Dr Atl)’s Landscape with Iztaccihuatl looks like an American Regionalist painting because, at heart, that is what it is; and a not very good one at that. Possibly the best and most engaging work in this show is photographic – Tina Modotti’s Telegraph Wires, Edward Weston’s more-Duchamp-than-Duchamp Excusado – but these are almost all by non-Mexican artists.

There is usually a reason for putting on a show like this – because it is on tour and therefore cheap to loan, because the museum that owns the work is being restored – but none of the usual reasons seems to apply in this case. Maybe it was just a bad idea.

To 29 Sept (royalacademy.org.uk)

NEXT WEEK Charles Darwent ponders the work of Dame Laura Knight

Critic’s choice

The six exuberant tapestries created by Grayson Perry and inspired by the recent Channel 4 series, All in the Best Possible Taste with Grayson Perry, are now on a national tour. The Vanity of Small Differences is at the Sunderland Museum and Winter Garden until 19 Sep. then it visits Manchester and Birmingham. Perry’s first two tapestries The Adoration of the Cage Fighters and The Agony in the Car Park are based on places and characters he encountered in Sunderland.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies