Dickens: Nightmare before Christmas

Charles Dickens was driven by demons when he wrote his much-loved yuletide tales. Award-winning author Justin Cartwright feels the pain

When I was asked to choose one of Charles Dickens's books to write about for BBC Radio 3's The Essay series on "the Writer's Dickens", I immediately picked A Christmas Carol, because Dickens's love of Christmas has always intrigued me. It came as a surprise to learn that A Christmas Carol is his most read book and that "Bah! Humbug!" is the best-known phrase in all his work.

Its popularity, I think, rests on the understanding that Christmas was deeply affecting to Charles Dickens and that A Christmas Carol was far more than a simple ghost story; it is trembling with emotions that come straight from the heart. Dickens himself reported tears as he wrote it. For him, I think, Christmas was a refuge from the memories that plagued him, memories of a childhood fraught with anxiety and mistreatment. The horrors of the time he spent working in Warren's Blacking Warehouse grew in his memory and came to represent all his insecurities and all his longings. He also came to idealise Christmas as a time of untrammelled happiness and peace, a respite in a harsh world.

From very early in Dickens's writing, Christmas is a favourite subject: Sketches by Boz of 1836, for example, has a story, "A Christmas Dinner", which describes a family Christmas party during which old resentments are forgotten and old wounds healed. Dickens wrote "Christmas time! That man must be a misanthrope indeed, in whose breast something like a jovial feeling is not roused – in whose mind some pleasant associations are not awakened – by the recurrence of Christmas." The memory of a child who has died also features: this story is very obviously the progenitor of Tiny Tim and the genesis of A Christmas Carol.

As a result of the Puritan interregnum and the Industrial Revolution, the traditional Christmas had lost ground over nearly 200 years, but now, in the early 19th century, a revival was taking place, soon to be helped on its triumphant way by Prince Albert's introduction from Germany of the Christmas tree. And Dickens was the high priest of the traditional Christmas.

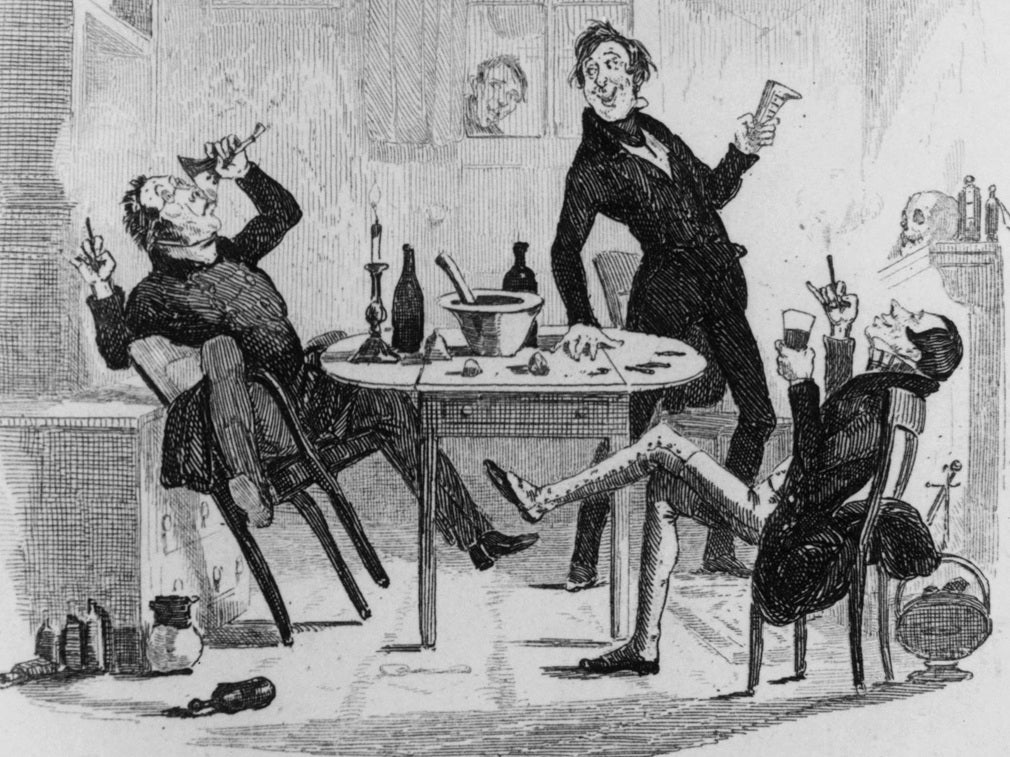

In The Pickwick Papers, Dingley Dell is the setting for a demonstration of how one generation passes to another the traditions of Christmas, which Dickens regarded so highly, traditions that the Wardle family had observed, from – as Dickens says – time immemorial. He paints a picture of a pre-industrial, even mediaeval, Christmas that places the happiness of the servants and the children at its heart. And as he became wealthy, Dickens loved to be at the centre of Christmas, the master of the revels. The whole family was enlisted to perform pieces he had written on Twelfth Night. It was clearly an antidote to his lifelong fear of poverty and disgrace, always a possibility in Victorian England, as his father had proved.

A Christmas Carol is about the working poor: Scrooge's nephew, Fred, and his clerk Bob Cratchit celebrate Christmas with a warm heart as best they can and they celebrate it for its own sake. When Scrooge describes it as a whole day of making money lost, Fred says: "I have always thought of Christmastime, when it has come round – apart from the veneration due to its sacred name and origin, if anything belonging to it can be apart from that – as a good time: a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time: the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys. And therefore, uncle, though it has never put a scrap of gold or silver in my pocket, I believe that it has done me good, and will do me good; and I say, God bless it!"

This is the authentic voice of Dickens. What is often seen as gross sentimentality in Dickens is the very real sense that he had been betrayed by his family: his mother, he said, was keen for him to be sent back to the blacking factory, for which he could never forgive her: "I do not write resentfully or angrily: I know how all these things have worked together to make me what I am, but I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back." In fact, he is writing with the deepest imaginable resentment and bitterness. In A Christmas Carol, Dickens takes a sensual – almost spiritual – delight in the abundance and open-handedness of Christmas; lavishness and plenty were to become another theme. This is his description of Scrooge's chamber transformed by the spirits: "Heaped up on the floor, to form a kind of throne, were turkeys, geese, game, poultry, brawn, great joints of meat, sucking-pigs, long wreaths of sausages, mince-pies, plum-puddings, barrels of oysters, red-hot chestnuts, cherry-cheeked apples, juicy oranges, luscious pears, immense twelfth-cakes, and seething bowls of punch, that made the chamber dim with their delicious steam."

There is an element of mythologizing in the story of the blacking factory, both by Dickens and critics. Warren's factory was in fact owned by a relative of the Dickens family who was doing the family a favour by taking young Charles on. But whatever the justification for sending him there, it was an appalling experience – as we read in David Copperfield: "No words can express the secret agony of my soul as I sank into this companionship. I worked from morning to night with common men and boys, a shabby child." His father, released from Marshalsea, once came to look through the window to where his son and other workers were on public display, much to Charles's utter confusion and humiliation. "I wondered," he wrote "how he could bear it." It seems that Charles may have started work there at the age of 11 rather than 12 as is generally accepted, and it is probable that he worked there for about a year. That time made him aware that he was on the edge of the abyss of social ruin.

In his autobiography, he wrote: "I know I do not exaggerate, unconsciously and unintentionally, the scantiness of my resources and the difficulty of my life... I know that, but for the mercy of God, I might easily have been, for any care that was taken of me, a little robber or a vagabond." It was the Victorian nightmare of social regression. So Christmas was idealized as the time when people were at their most affectionate and generous. There is something moving and even a little desperate about Dickens's love of Christmas.

When I was a boy in South Africa, Dickens was one of the first writers I got to know well. His books opened a door to an unfamiliar, mysterious, richly comic and very human world. I longed to be able to understand it and experience it.

In South Africa we gave each other Christmas cards of traditional snow-scenes, and we incinerated our Christmas pudding with the help of brandy. My father was something of a Dickensian character himself, good-hearted but inept, and almost incinerated himself in the process one year. The traditions of Christmas were keenly observed, in the blazing heat of midsummer. I love the tradition still and for the same reasons as Dickens – the security, the sense of continuity, the compassion and the feeling of being in some way more human. But as I write this, I wonder if I didn't acquire these feelings from reading Dickens. I was at boarding school for nine long years, a thousand miles away from home, and even now I sometimes feel that aching emptiness that Dickens evokes with such skill. I would hide in the dormitory in the afternoon to read, desperate to get away with the help of books from the airless world of the boarding school. It would be unfair on my kind parents to say I felt abandoned, but what I did feel – and I recognise in Dickens – was a sense of never-ending emptiness, of days stretching out interminably, full of pointless rituals and shot through with the fear of punishment.

To this day, I can remember the deadness of the Sundays when those who had no relatives or friends living nearby, spent the day in dreadful limbo; the other boys would come back from their homes in the evening, full of accounts of fun and lavish food, and those of us who hadn't been asked out – it had to be formally requested by a parent – would sit silent and miserable over the Sunday evening soup. Soup and deprivation had for many years an affinity in my mind.

When I was a young man, with aspirations of being a writer, I turned against Dickens. He seemed to me then to reside in a deeply artificial and overly sentimental universe. The truth is, Dickens is sentimental, and sometimes shallow, but what I came to see clearly was his craft. Writing is, after all, just the act of creating new and believable life on the page. And Dickens has created richer and more memorable characters than any writer in history.

Dickens also has an astonishing ability to manipulate our sympathies and to direct our affections to the more human of his characters at the expense of the bogus, the pompous and the cruel. I particularly enjoy his lampooning of lawyers. But most of all, I appreciate how he rejoices in humanity and I also see, after living here for many years, just how his writing fostered the belief that good-heartedness is an indispensable British virtue. And I see more clearly than ever after reading it again that A Christmas Carol contains many of Dickens's obsessions, the obsessions that drove him on, and they include the love of Christmas, redemption for children and kindness.

J M Coetzee wrote recently, "Art that is not great-souled, as the Russians would say, that lacks generosity, fails to celebrate life, this art lacks love." Dickens celebrated life as no other writer has ever done. He was indeed great-souled.

BBC Radio 3 will broadcast Justin Cartwright's essay on Friday at 10.45pm as part of its week-long series, 'The Essay: The Writer's Dickens'

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies