Edited extract: Alexander McCall Smith’s introduction to the new Folio Society edition of Margery Allingham’s ‘The Tiger in the Smoke’

A far-fetched, 1950s noir: just perfect for the modern world

Margery Allingham was one of the greatest mid-20th-century practitioners of the detective novel. She published her first novel in 1923 at the age of 19, and her last appeared posthumously in the late 1960s. Between those two milestones, she wrote numerous novels, novellas and short stories, mostly, but not exclusively, concerned with detection. Her books are not mere potboilers, but are well-written, often quite subtle studies of social and psychological issues. In the annals of crime fiction she stands out, in Agatha Christie's words, "like a shining light".

She had ink in her blood, both her parents having been journalists who wrote for and edited popular magazines. It is not surprising, then, that Margery Allingham took naturally to the world of middle-brow fiction of the sort that might as easily find a home in newspaper serialisation as between book covers. Her books are far less static than many crime novels of the period: there are romps in these books; there are treasure hunts; there are all sorts of asides.

The Tiger in the Smoke was first published in 1952. It is generally regarded as being one of her best works, and there is certainly a case for regarding it as an important landmark in the development of the modern crime novel. It is unusual in that there is no central crime to be solved: we know who the principal villain is, although there is a mystery as to why he is planning a bizarre programme of impersonation. While it has an intense period feel – reading it today one gets a very strong sense of England in the post-war years – the central plotline, which is that of a dangerous psychopath carrying out a series of ruthless killings while he eludes capture, has a rather modern feel to it. One gets the sense that, suitably updated, it would serve very credibly the requirements of a contemporary thriller or even a piece of Scandinavian noir.

The plot is, of course, far-fetched - a hallmark of much of Allingham's work. There is a search for a treasure. Coincidences abound, and everyone seems to know everyone else, or at least know of them. That, of course, may well have been the case in real life: we forget just how tight a society Britain was in those days. It must have been horribly oppressive, and indeed the sense of a society on the cusp of major change is present in this particular book. The reference to National Health spectacles is more than a description of spectacles: it is a social and historical pointer.

Margery Allingham's achievement is to combine an atmospheric account of London in the post-war period with both strong and vivid characterisation and considerable dramatic tension. The atmosphere of London is painted with an accomplished brush. Fog – or smog – plays an important part in this: an ideal medium for Havoc, the psychopathic murderer, to sneak about in.

The characterisation is strong and, for the most part, believable. Albert Campion, Allingham's major creation, is mature at this stage of his career, and comes across as quiet and considered, a likeable hero. Lugg, his manservant, is downright odd, and speaks in a way that is distinctly peculiar. Geoffrey Levett takes in his stride his kidnapping by a street band. Such chaps did. The street band is an extraordinary concoction, and features an albino and a dwarf. Yet it is a lovely creation, and gives the author the opportunity to say a lot about the world of the marginal ex-servicemen trying to survive on their wits in an unsympathetic world. And the notion that somebody might be kidnapped by such a band, have his mouth taped up, and then be pushed along under the nose of the gruff local copper, is so boisterous as to be positively enjoyable.

Yet there are many more serious passages that provide a fascinating glimpse into the mores of the time. The character of Uncle Hubert, the Canon, is beautifully drawn, and there is an extraordinary scene in which Havoc and the Canon meet. This results in violence, but the effects of the Canon's words on the nature of the soul are sufficient to make it harder for Havoc to wield his knife with his accustomed deftness.

Since our contemporary thirst for naturalism is so strong, there will be many readers who will find Margery Allingham – along with many other writers of her period – just a bit too far-fetched. There is certainly a plausibility issue with her work, but this is more than compensated for by the wit and by the psychological acuity of her writing.

These novels – The Tiger in the Smoke in particular – are wonderful period pieces. They are highly readable and, in their way, curiously memorable. They say things about human nature that are still true: The Tiger in the Smoke leaves us thinking about evil and human choice, and about how people end up being, in the Canon's striking words, the people they are when they are alone with themselves. That, along with its vivid characterisation and its social detail, is more than enough to make its preservation amply justified.

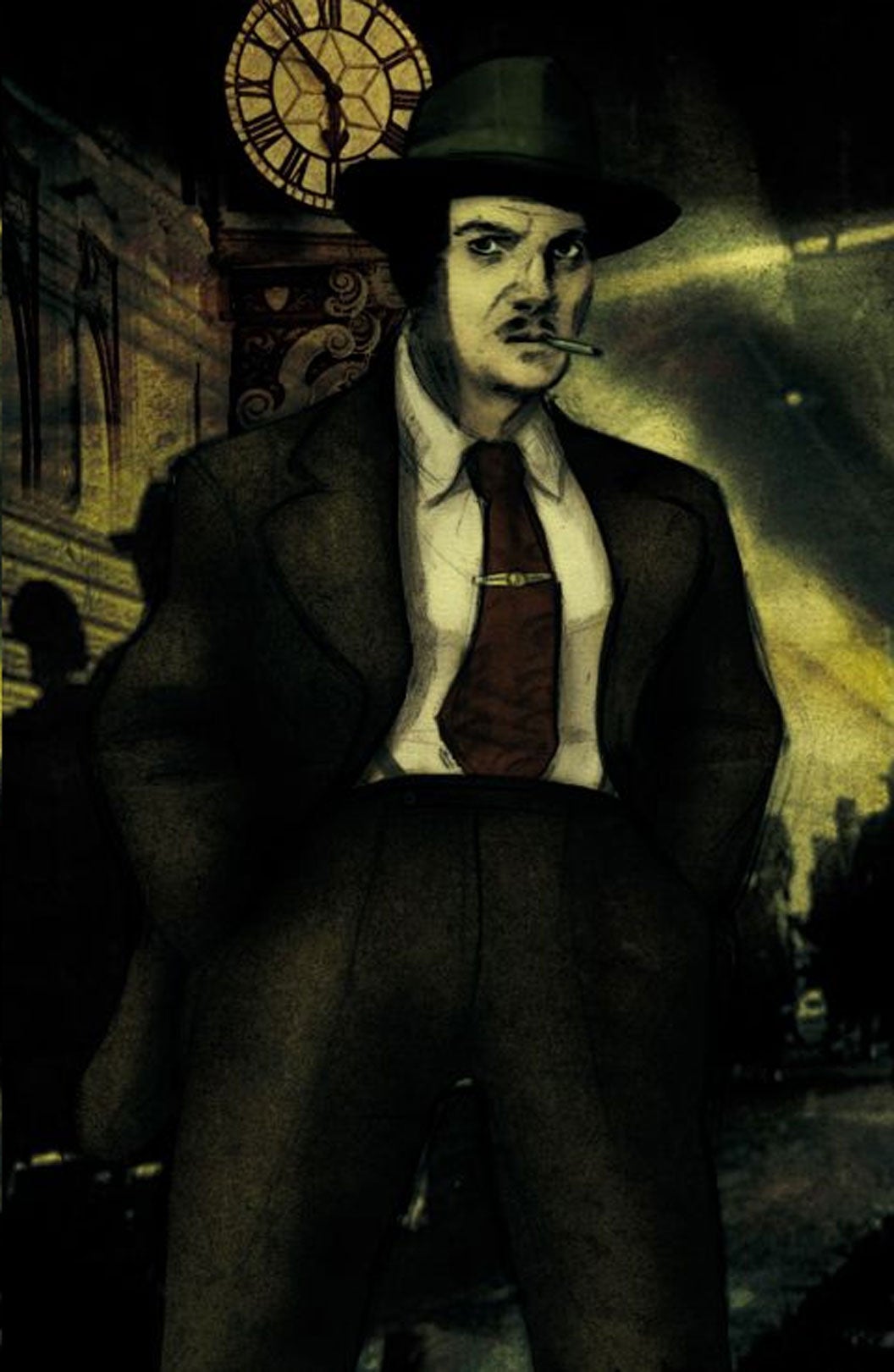

The Folio Society edition of Margery Allingham's 'The Tiger in the Smoke', with an introduction by Alexander McCall Smith and illustrations by Finn Campbell-Notman, is available from foliosociety.com at £27.95

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies