Encyclopedia Britannica: The end of its shelf life

Its current print run will be its last ever. John Walsh mourns the end of 244 years of bourgeois self-improvement

It's a sad day for fetishists of gold lettering. It's a bitter blow for door-to-door salesmen. It's a major frustration for recently nominated godparents wondering what christening gift would combine the solid, the stylish and the edifying. The print edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica is no more.

The company has announced that henceforth it will concentrate on their online encyclopaedias, and that the last-ever print edition – a mighty, 32-volume set weighing 129 pounds – won't be replaced when the last 8,000 sets are finally sold.

Devotees of reference books have seen the writing on the wall – sorry, the characters on the digital screen – for some time. They've watched as the hungry maw of the internet gobbles up sales of dictionaries, thesauruses and "companions," and the Wikipedia site has become – in a single decade – the only destination for seekers after factual knowledge of both humanities and science subjects.

But what a rich history has been lost with the end of these great heavy tombstones. They were first published in Edinburgh between 1768 and 1771 and, by 1809, had grown from three volumes to 20. Noting the public's thirst for knowledge, the owners signed up eminent writers and subject experts, and started an unprecedented project of continuous revision. In the 20th century, the books hit the big time. Their American owners had the articles simplified for a wider market, and proceeded to flog them to everyone. Door-to-door salesmen, their car-boots straining under the weight of erudition, urged householders to invest in the 20-volume sets because they contained "the Sum of Human Knowledge." Sure they cost several hundred quid/dollars (they said) – but isn't your child's education worth the money?

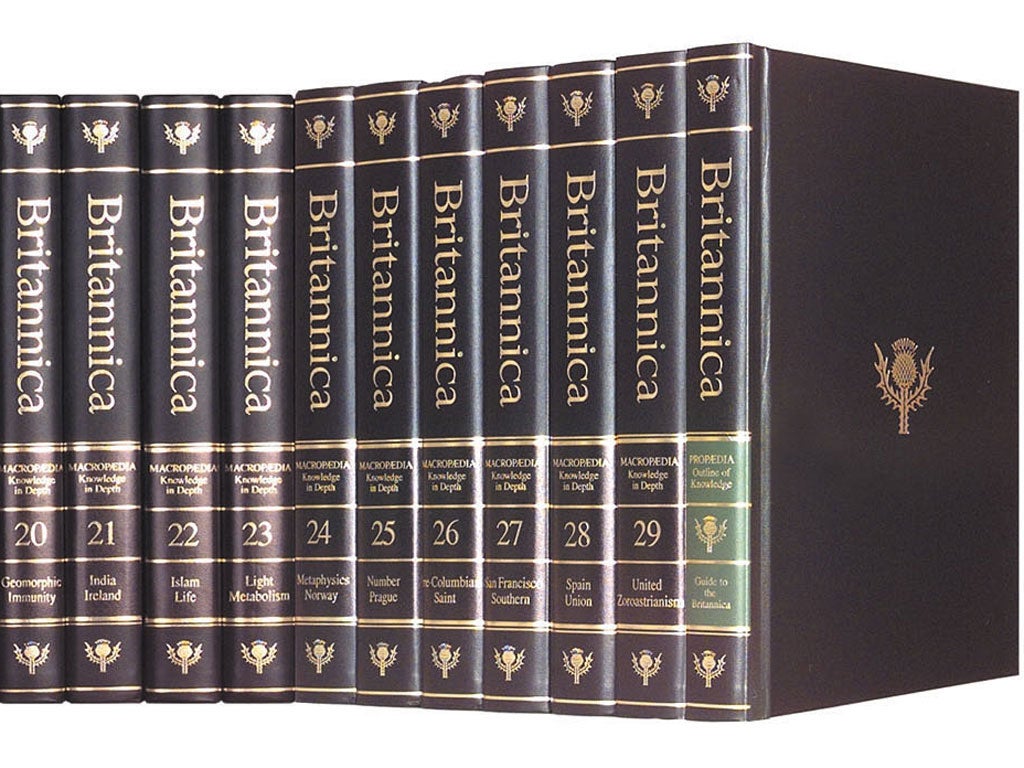

The books became more handsome and striking – an array of spines that commandeered the family bookshelf like a brilliant army in smart, leatherette uniforms.

For the aspirant middle classes in England and America, they were often the first books the family owned. Were a child to ask its parents, in a piping treble, who Tutankhamun was or what was the capital of Paraguay, they'd be directed to "look it up" in the family Britannica. (It meant the parents could bypass the embarrassment of not knowing the answers.)

Sad to report, the books themselves weren't always right. Examples of the most egregious inaccuracies have howled down the centuries. The chief editor of the (1790s) third edition, one George Gleig, decided unilaterally that Newton was wrong about gravity and announced that it was, in fact, caused by "the classical element of fire." The 11th edition (in 1910-11) didn't think Marie Curie, who'd just won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry to go with her Nobel Prize for Physics in 1903, worthy of an entry, being a mere woman, but it gave her a name-check in the entry on her husband, Pierre.

Now that it's all available online, mistakes and out-of-date entries can be updated and revised at a moment's notice. It makes for more streamlined access to the Sum of Human Knowledge – but how sad to think it's brought down the curtain on 244 years of bourgeois self-improvement and directionless browsing.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies