Michael Arditti interview: 'From the Church to the newspapers... What shall I do next, the NHS?'

Moral dilemmas are always at the heart of Michael Arditti’s novels and his latest book Widows & Orphans is no different

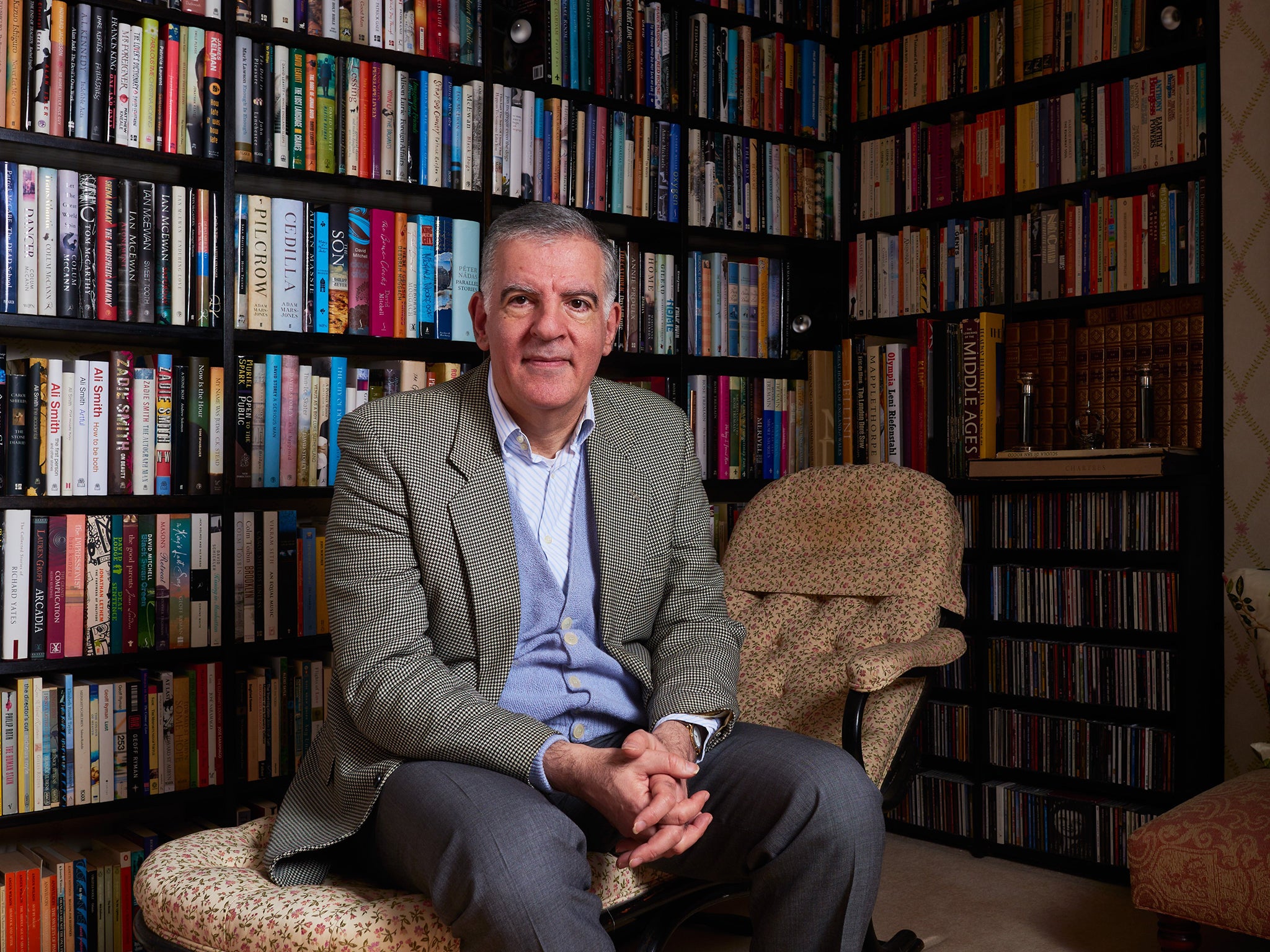

As I ring the doorbell of Michael Arditti’s top floor, north London flat, the nearby church clock chimes three. It seems appropriate that a writer whose work has so often focused, “unfashionably” he says, on the role of faith in Britain should live within earshot of his local place of worship.

His novels – from his first, The Celibate (1993), about a young ordinand experiencing a spiritual and sexual crisis, and including his famous contemporary Passion story Easter (2000) – tend to explore themes of morality and modernity, often using the Church as a stage. His latest, however, uses a different struggling British institution – a local newspaper – as a lens on a community going through upheaval and change. “From the Church to the newspapers,” he laughs. “What shall I do next, the NHS?”

Widows & Orphans is set in a fictional, seaside town, where the local newspaper editor and proprietor, Duncan, is a typically Arditti anti-hero. Talking about his last novel, The Breath of Night (2013), which was set in 1970s Philippines (he actually met Imelda Marcos while researching it), Arditti explained that “both [characters] are trying to do what’s right, within the confines of their own upbringing, and when faced by a world that they find it hard, initially, to relate to”.

While Widows & Orphans could not be more different in setting, this search for firm moral ground in an unsteady world is as dominant a theme as ever.

Books highlights of 2015

Show all 6“I think that even if I wrote a book about, you know, fighter pilots in the First World War,” he says, “it would probably be about the morality of whether they should be fighting, rather than about the bang bang, shoot shoot bit.”

In the case of Widows & Orphans, Duncan’s crew is a motley team of journalists who are struggling to keep afloat the newspaper that Duncan inherited from his father and grandfather. Arditti certainly has a talent for throwing disparate characters together: a love affair on a pilgrimage to Lourdes in Jubilate; a gay curate, a stuck-up couple and a homeless man in a church, in Easter; and now, a small, dysfunctional family of hacks. “I wanted to write about what it is to be in a community today,” he says. “And a newspaper became a wonderful nucleus because it’s both reporting social changes … and affected by them.”

Despite having worked for newspapers since becoming the Evening Standard’s deputy drama critic in the 1980s (as well as being a successful playwright), he has hardly ever visited a newspaper office and spent some time at two London papers to get a flavour for this novel. “There’s a very important character, to me, the little girl with cerebral palsy,” he says. “I actually spent much more time talking to speech therapists and people who knew about cerebral palsy because … it’s sort of iniquitous if you get those sorts of things wrong.”

What he did enjoy, though, was writing the little news story which opens each chapter. Only one of which, “well-loved caretaker retires”, came from a real paper, apparently. “It was like making up lots of little, tiny short stories, some of which are very sad, and some of which are funny.” The reports bring news of a blaze at the pier, or dogging on the cliffs, as Duncan tries to draw an ethical line with his head of advertising sales and fend off the unscrupulous local developer who wants to rebuild the town’s treasured historical asset as “Britain’s first X-rated pier”. Thrown in are several troubled teenagers, a vicar struggling with his sexuality, two wonderful elderly mothers, a disgraced picture editor, and a host of other minor characters with beautifully filled in interior lives and back stories.

I suspect that Bible readers often become writers and lovers of words, and Arditti agrees. To him, it’s a combination of the “mystery” in the words, the “richness” of the stories and a sense of “interpreting something bigger, and thinking about a world outside yourself”. He adds: “I think we’re very lucky to have it .... But also it’s done a lot of damage. Sorry, that’s wrong, the way people have used it has done a lot of damage.”

Arditti’s characters disagree about how to interpret the Bible – and whether to interpret it at all. In several of his novels – notably The Enemy of the Good, Easter and Widows & Orphans – a visual artist produces a modern interpretation of a Biblical myth which causes controversy among more conservative parishioners. Arditti strongly believes that it is the role of art, including fiction, to constantly re-evaluate faith and spirituality for a changing world, and he is angry with some of those who claim that their own interpretation is unassailable.

“I’ve learnt so much about how the Bible was written and translated and edited and distorted .... And the idea that anybody can just take the Bible as literal truth is just absurd. Because if there is any truth to the idea that we are in some ways, as human beings, privileged creatures, made in the image of the creator, that is that we have been given the ability to morally discriminate. We’ve been given minds.”

He is insistent, also, that religions are not really in conflict with each other but rather “the fundamentalism in all of these religions is against the liberalism in all of them … all the people of, I’d like to say good faith but perhaps I should say liberal faith, in these religions have far more in common than the people with fundamentalist values in individual religions.”

He has even tackled the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, about his policies on gays in the Church. Apparently, he was very sympathetic and said “yes, but it’s much more complicated than you think”. Arditti says that his next novel explores the way that a biblical myth was first created, and then has influenced people in different epochs from the Babylonian exile of the Jews up to the present day. It contains several parts, including a medieval mystery play set in York, and, I hope, at least one character trying to do the right thing in a complicated world.

“If you open yourself to experience as a writer, everything encourages you, helps you to write,” he says, “but sometimes you’ve got too much in your head and you’ve got to filter it. I’m better at doing that than I used to be. I think when you write your first one or two you’re never sure that you’ll write any more, so you feel that you should put quite a lot in. But this is my tenth book, and I hope I’ll write an eleventh ….”

I’m sure he has material for a lot more than that.

Extract from Widows & orphans by Michael Arditti

‘Emerging from his reverie with an acute sense of loss, Duncan was tempted to approve the dummy front page with its one-word headline, “Gutted”, above a photograph of the pier head smothered in smoke … but he shied away from the twin offences of sensationalism and sentimentality. Now, more than ever, he was determined to stick to the standards for which the paper was known – and, in some quarters, ridiculed.’

Arcadia Books, £14.99

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies