Bedouin of the London Evening by Rosemary Tonk, book review: Mystery of the vanishing poet is finally resolved

As Astley reveals in his introduction, many life blows ground Tonks down, and an involvement in evangelical Christianity led her to reject poetry, especially her own, as Satanic

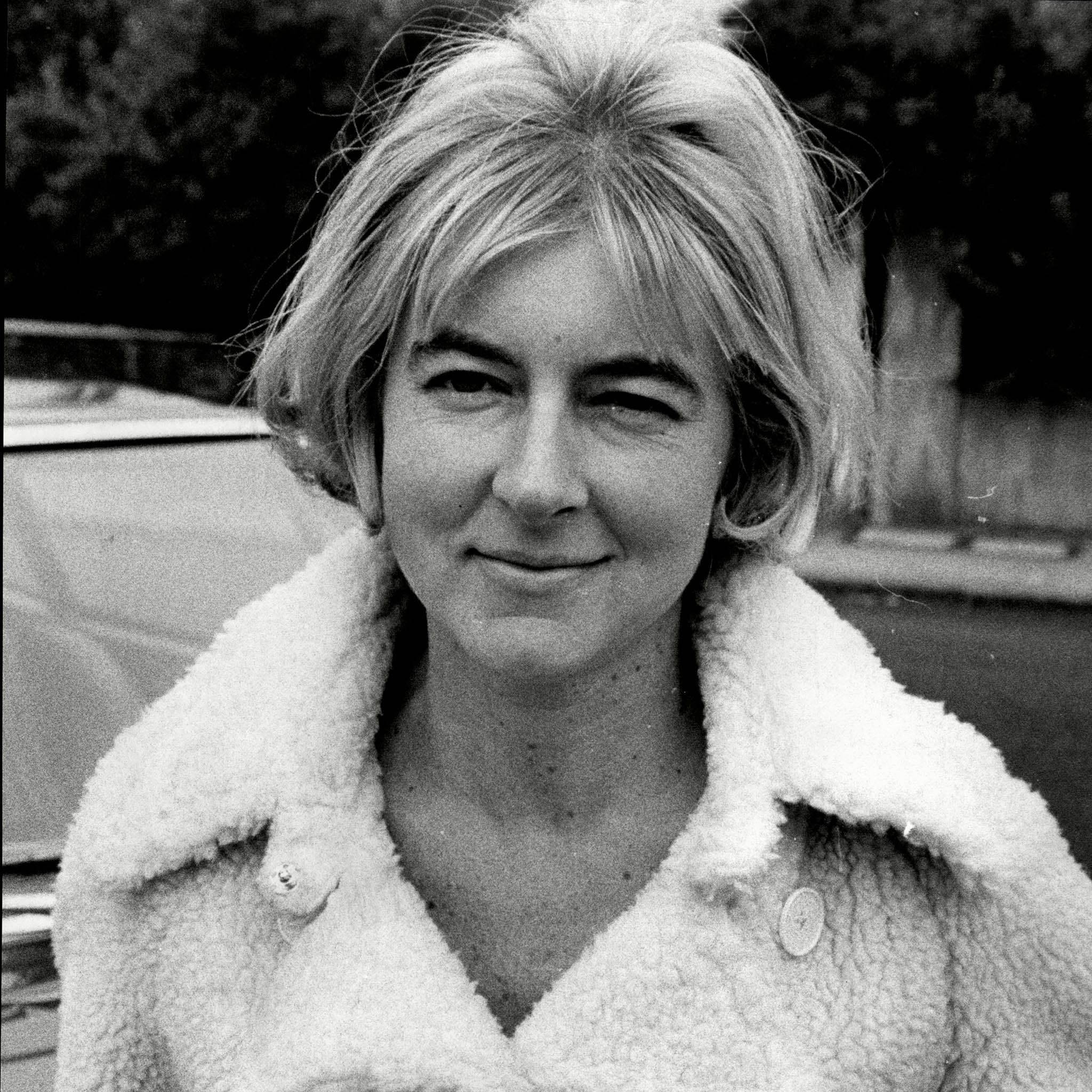

In the 1960s and early 1970s, Rosemary Tonks was as plugged into the London literary scene as anybody could be.

Based in Hampstead, she was rated by Larkin, who included two of her poems in The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century Verse. She was on good terms with key poetic figures, reviewed regularly and went on radio. She wrote six novels and two collections of poetry; Neil Astley, the editor of this volume, calls them “epoch-defining”. And then, like her hero, Rimbaud, she turned her back on poetry and disappeared.

Astley is to be commended for tracking down this elusive figure and solving the mystery which has tantalised poets and critics ever since. The decades of silence ended with her death this year, aged 85; at last, the writing she suppressed can be read again. This volume comprises the two collections, Notes on Cafés and Bedrooms (1963) and Iliad of Broken Sentences (1967), with some “Selected Prose”, which is scanty but revealing.

Tonks was born in Gillingham in 1928, making her the same age as Anne Sexton, and four years older than Sylvia Plath. Her poems have a youthful relish of seediness and sadness; their settings are hotel rooms and cafés, in cities that seem always to be fog-bound; the mood is one of ennui shot through with lightning-bolts of fierce emotion. The props are often domestic but her cabbages, suitcases and dressing-gowns take on a weird glow.

Her exuberance – she loves exclamation marks – is undercut by a profound alienation that is touched on in the revealing interview also included in this volume. “I wish I had somebody in mind [when writing poems], but I feel extremely alone, I may say.” The poems can be read as self-dramatising or slyly funny – or both: “On the way to a restaurant, my youth was lost … I have been young too long, and in a dressing-gown / My private modern life has gone to waste.” (From the title poem.)

“Story of a Hotel Room” is well known, with its wonderful last lines warning her generation that sex can rarely be casual: “To make love as well as that is ruinous /… – If the act is clean, authentic, sumptuous, / The concurring deep love of the heart / Follows the naked work, profoundly moved by it.”

It’s poignant to think her first collection came out in the year Plath died, and it’s hard not to dream up connections. Like Plath’s The Colossus, many of the poems in Tonks’s first collection, though technically adept, are somewhat mannered, occasionally giving the impression of clever writing exercises. But an intriguing poetic personality is lurking in there, and like Plath, Tonks made an extraordinary jump with her second collection, arriving at a confident and utterly distinctive voice. Like Ariel, Iliad seems to open new doors in poetry; like Ariel, the new beginning was also an abrupt end.

As Astley reveals in his introduction, many life blows ground Tonks down, and an involvement in evangelical Christianity led her to reject poetry, especially her own, as Satanic. It’s an astonishingly sad story.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies