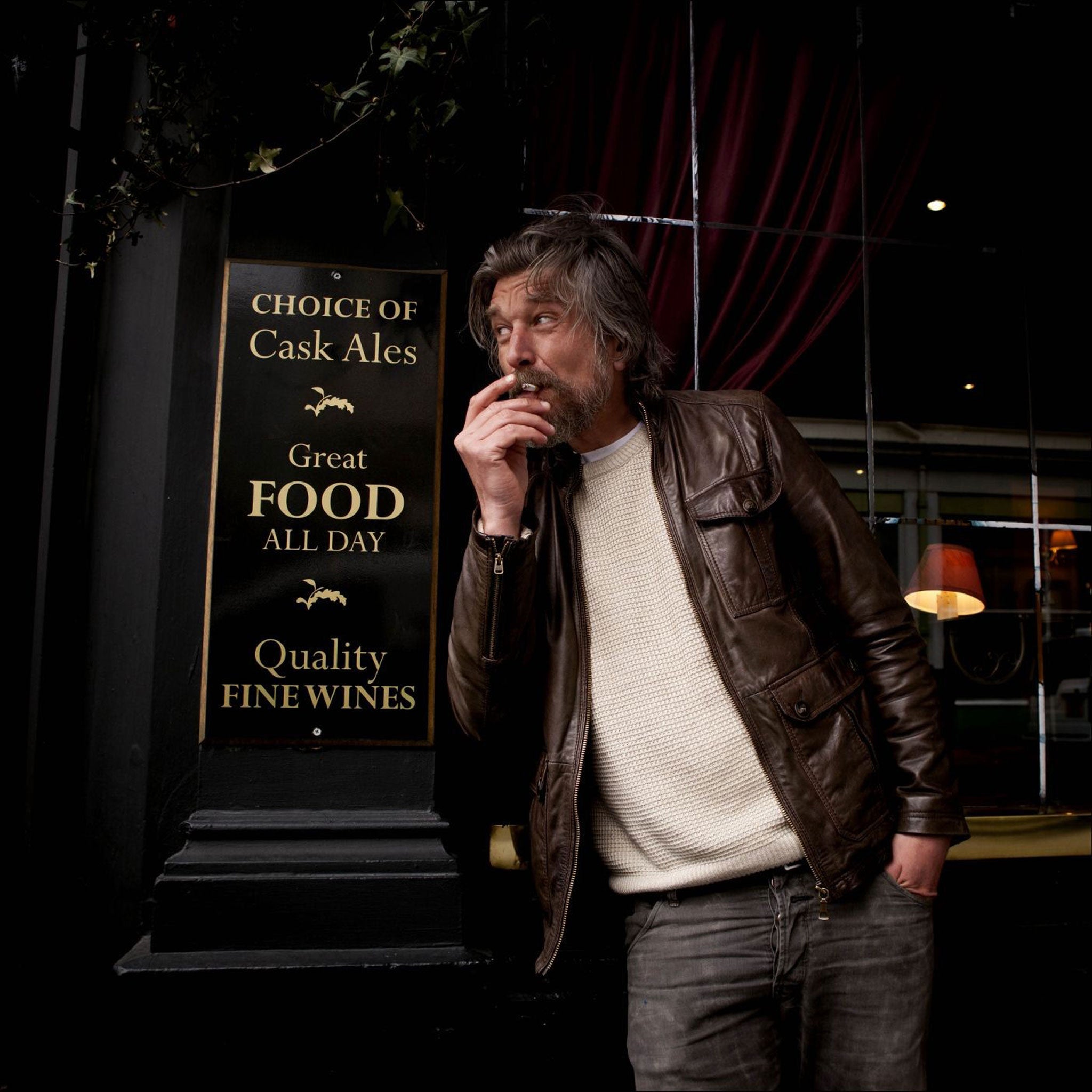

Boyhood Island: My Struggle 3 by Karl Ove Knausgaard, trans. Don Bartlett, book review

Symbolic power of near-adolescence infuses this third autobiographical novel

Much has happened to Karl Ove Knausgaard in the four years since I saw fellow-writer Per Petterson gesture to a row of volumes on the bookshelves at his farm east of Oslo. With admiration and not a little awe, Petterson told me how the six-part, 3,000-page confessional epic of Knausgaard's My Struggle had come to obsess Norwegian readers. Firms even had to ban coffee-break conversations about the books. Since then, the virus has spread around the world. Norway's literary frenzy has swollen into a globe-spanning cult.

Translated again by Don Bartlett with an intimate sureness of tone and touch, Boyhood Island is the third instalment in this sequence of autobiographical novels. A Death in the Family, the first, plunged us into the adolescent front-line of Karl Ove's war with his troubled teacher father, and then rushed on to the story's devastating end. A Man in Love gave us a portrait of the artist as a young parent, and spouse, wrenched between prose, passion – and the pram. As its title hints, Boyhood Island stands almost alone. It covers the seven years of the 1970s after school begins for Karl Ove on the small island of Tromøya off Norway's southern coast. In spite of brief flash-forwards, this island story feels self-sufficient: as a place, a period, a stage of life. New readers might start here. "From the bottom of the well that is my childhood," Knausgaard fishes his haul of jewelled memories, traumatic episodes and indelibly burnished images. They glow with all the radiant colours of the island's springtime woods and lakes. Yet little Karl Ove did not just enjoy the timeless infancy of a Romantic poet, lost in the "immense antiquity" of sublime nature. He grew up on a brand-new middle-class estate, a semi-rural outpost of social democracy, occupied by "modern 1970s people" in the optimistic heyday of a "planned" society.

Knausgaard makes plain that "Zeitgeist comes from the outside, but works on the inside". This "revolution" intersects at every point with the elemental joys and dreads of boyhood. Knausgaard spares us too much overt reflection in order to maximise the power of every jaunt, scrape, crush, cult and (quite often) spell of terror and bout of weeping. For these early years are overshadowed by a fairy-tale father. In spite of his career as a go-ahead teacher, scary dad stalks ogre-like across these pages: "the terror never let up". His beloved mother, a cheerful, caring psychiatric nurse, embodies the benign spirit of the age. Furious father, prey to half-glimpsed demons of anxiety, unites the punitive control instincts of a bureaucratic state with the wrath of woodland trolls.

On this island of time, the old and the new forever coincide. Deep in the archetypal forest lies a squalid but alluring refuse tip. As puberty strikes, Karl Ove and chums will scour it for the porn mags that serve as sacred yet accursed icons. Behind all the Seventies pop-cultural allusions – Status Quo, Queen and Slade; Kevin Keegan and Kenny Dalglish; John McEnroe and Wilbur Smith; Norwich, Stoke and (wild-child Karl Ove's favourite) Wolves – loom the shades of myth. Not only the "intense thrill" of nascent desire but the "kingdom of death" lies all around the growing boy. Despite the hallucinatory detail, never forget Knausgaard is writing symbol-laden fiction. When, near the finale, the fledgling adolescent leaves for high school and "stops praying to God", he marks the rite of passage by scrumping a plump and juicy apple. We get the point.

This Bildungsroman charts the early sins of a serial transgressor. Like Joyce's Stephen Dedalus, Karl Ove will not serve. "Hatred" for his father breeds a rebel who says what he should not and (another emblematic scene) "keeps watching" a surgical operation on TV even though "the heart should not be seen". Via his visceral, immersive art, Knausgaard makes the heart visible as he conjures "the intensity that only exists in childhood". With skin-tingling immediacy, Boyhood Island transmits "the excitement that exists in the unseen and the hidden".

Join Karl Ove on 1970s Tromøya and you might never want to leave.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies