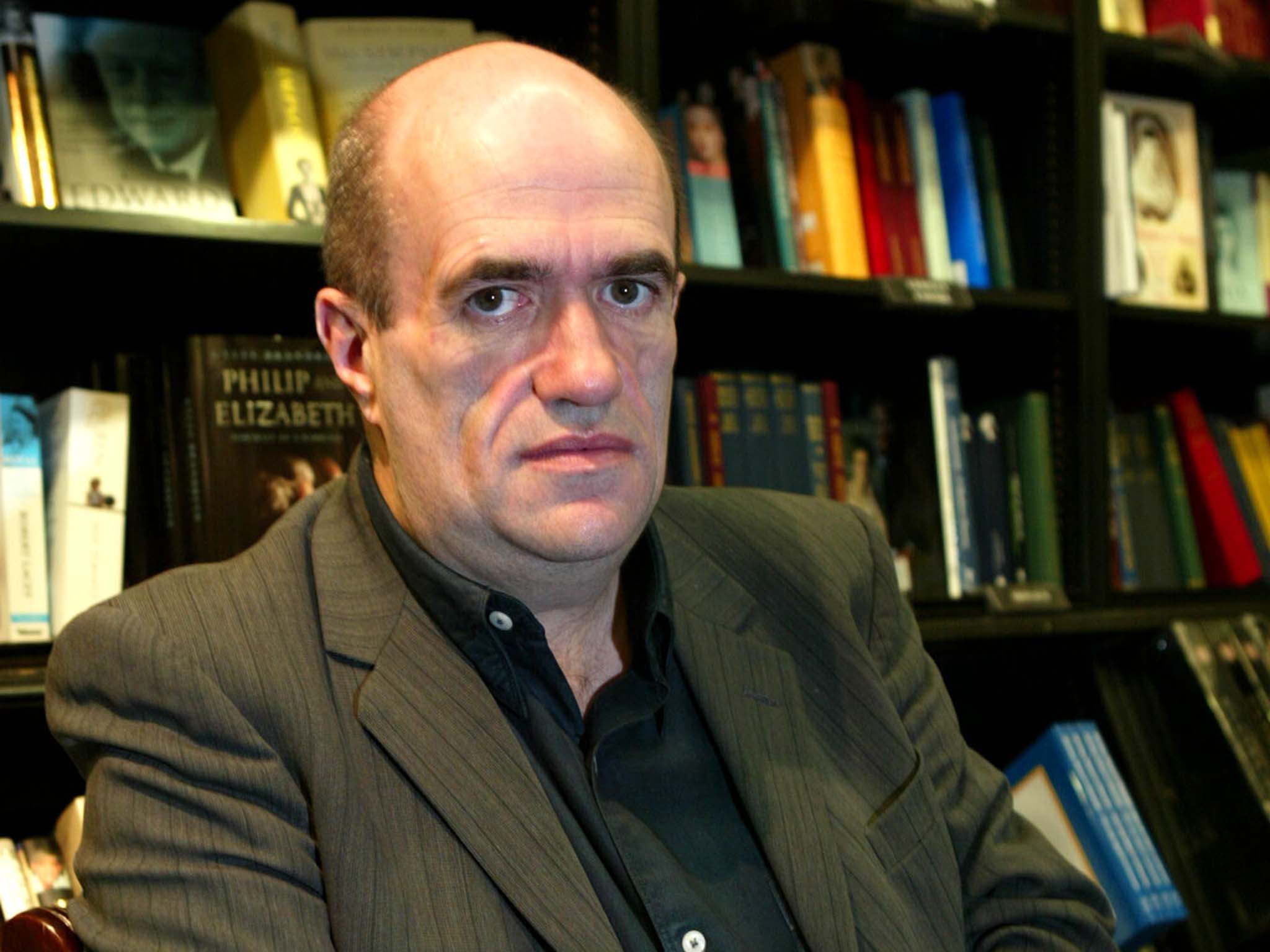

From Fifties New York to biblical Jerusalem, settings vary in Colm Tóibín’s fiction.

Enniscorthy, in the south-east of Ireland, however, is the location for his “Wexford novels”, which include The Blackwater Lightship (1999) and his transatlantic masterpiece Brooklyn (2009). This fictional universe is enriched whenever he returns to it, and the region where he grew up is for Tóibín what Nottinghamshire was for D H Lawrence: “The country of my heart.” In his new novel, Nora Webster, its yearning souls, political undercurrents and rolling countryside feels increasingly urgent and sophisticated.

Tóibín’s previous novel, The Testament of Mary (2012), combined two of his favourite subjects, loss and motherhood, as a grieving Mary told Jesus’s disciples: “The world is a place of silence.” The eponymous protagonist of Nora Webster is mourning her husband, Maurice, and her neighbours’ token condolences isolate her in “the hard world” which appears indifferent to tragedy. We admire Nora’s intelligence and strength as we follow her through the late Sixties and early Seventies, as she raises her sons, Donal and Conor, with help from her daughters, Fiona and Aine, when they return from college. If you’ve ever been part of a single-parent family, the depiction of the tough, intimate period of adjusting to new circumstances will stir memories.

Nora senses that her children and sisters share an understanding that she lacks. This might stem from her difficult relationship with her late mother, but is Nora excluded or does she alienate people? Incidents involving family members and work colleagues make us question her judgement. In Brooklyn, Nora and Maurice were described as “the nicest people in the town,” but characters exaggerate and alter their stories depending on who they’re talking to. Where it says in this novel that “she knew so much about people in the town,” I scrawled a big question mark in the margin.

Her neighbours’ inner lives are mysterious and Nora’s memory isn’t always reliable. The Church’s influence in Enniscorthy means people never seem to be entirely in control of their own fates. Sister Thomas, an elderly nun who keeps an eye on Nora, can be kind but her advice is often instruction. The way characters confide in each other (“I shouldn’t tell you this but …”) allows Tóibín to explore the role of storytelling. Gossip sometimes contains important information, especially when a trade union is formed at Nora’s office, while individuals shape the town’s mythology by telling anecdotes.

Tóibín’s eye for details, down to Nora’s clothes, the atmosphere in a village pub and Enniscorthy’s social hierarchy, can make the novel read as a pastoral about the non-swinging Sixties, where the centre holds and there’s no flower power or feminism. Soon, though, the “lingering unease” in Nora’s house is mirrored by the outbreak of violence in Northern Ireland. Nora’s response (“I just thank God that we’re living down here, miles from it all …”) is naïve because every community will register the impact of the Troubles.

Nora’s brother-in-law, Jim, a former IRA man, comes across less as an individual than a type of Irish republican. Another misstep concerns Donal’s photographs of television footage of riots and space exploration. They sound self-consciously Postmodern for a schoolboy photographer, and illustrate certain themes a little too neatly, although they raise interesting ideas. “I am g-going to miss the l-landing,” Donal says. “All the photographs I had were j-just l-leading up to that.” His stammer, which never goes away, articulates his grief and potentially reflects society’s ruptures. What is Donal trying to capture with his camera? Does he picture his father in the abyss beyond the screen? The novel examines borders, the division of Ireland, and the liminal one between living and dead.

We root for Nora when she makes friends and discovers the “imagined life” of classical music but her children remain troubled. “I sit in the classroom he came into every day,” Donal says. He shouldn’t need to explain to his mother that attending the school where Maurice taught is upsetting. I admit, however, that it hadn’t occurred to me and Nora’s inconsistencies often match our own. Perhaps it’s misguided to judge her as a mother. Perhaps Philip Larkin was half-right when he wrote: “They fuck you up, your mum and dad.” Perhaps failure is an inevitable part of being a parent and of being a son or daughter.

Last year, Tóibín made a remark about Seamus Heaney’s poetry which applies to Nora Webster: “Every phrase is weighted with care.” This novel deserves to be read as closely as Nora listens to Beethoven. It leaves you with much to ponder and impatient to return to Enniscorthy. You needn’t have read the other Wexford novels to appreciate its depth and subtlety. Our bond with the Websters makes us imagine they’re out there, living and longing, with fire crackling in their hearth.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies