Perfect Wives In Ideal Homes by Virginia Nicholson, book review

Parallels can be drawn between young women of the 1950s and today's have-it-all generation

Memories are composed of brands. In her introduction to this richly detailed book, Virginia Nicholson lists the ones she remembers from her own 1950s childhood: "Spangles, Shippam's fish paste, Pond's Cold Cream, Orlon cardigans, Morris Travellers, Player's Navy Cut, holiday camps, hostess trolleys – and, of course, Coronation Chicken."

What were they like, the young women growing up in this world? Nicholson has set out to uncover and reconstruct their stories: "theirs will be at times a narrative of fears, frustrations and deep unhappiness, but it will also be one of ambitions, dreams and fulfilment."

Girls were certainly up against it. They had to work hard to make up for their perceived inferiority. They could try to do this by going shopping. The crucial commodities a young woman required fell into a narrow range: the right toiletries, clothes and cosmetics. Women's magazines earnestly instructed their female readers how to attain perfection through self-control and artifice. Roll-on girdles for body and soul.

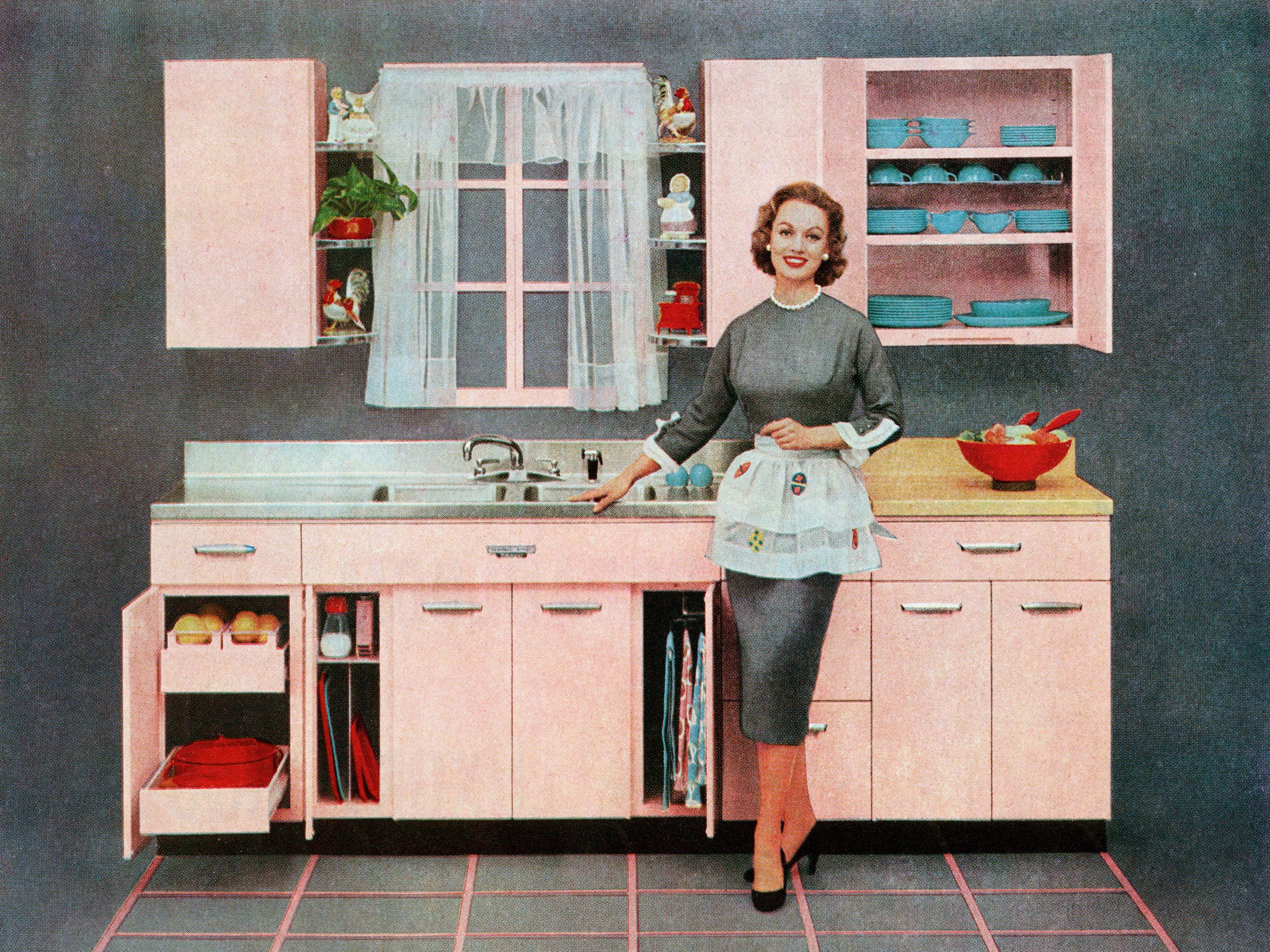

Such advice was subverted by the late Angela Carter, that scalpel-wielding novelist and satirist, who argued that femininity was a masquerade. For her, a Real Woman was merely a mannequin in an elaborate costume. Looking at 1950s fashion plates and advertisements, we can certainly agree. These wasp-waisted living dolls wearing impossibly high heels, crinoline-style bouffant skirts and tiny frilly aprons suggest parody, caricature.

Such images seem quaintly distant from our own age and yet they also feel close to it. The 1950s was an age of anxiety about women's responsibilities and freedoms, and ours is similarly so. Women nowadays have supposedly progressed, supposedly have it all, and so are censured for whingeing if they dare to complain about unequal pay, sexual harasment, rape, the unequal division of household chores. The 1950s have re-emerged as a source of nostalgic imagery both to express and to hide female conflicts around work, love and childcare. We can mock fads for cupcakes and flowered ironing board covers while recognising our desires for modern life to be less speedy and stressful.

The 1950s did not, of course, confine women to the domestic sphere in any simplistic way, as Rachel Cooke shows in her splendid recent book, Her Brilliant Career – Ten Extraordinary Women of the Fifties. The Victorian ideal of the idle woman kept by her husband as a status symbol only applied to the bourgeoisie and upper class. Most women worked unpaid, inside the home, and many simultaneously worked, badly paid, outside it. Nicholson's study focuses on both the "ordinary" women of the 1950s, who had little money and struggled for education, and their wealthy, privileged sisters, from the Queen downwards.

Feminists have long argued over whether women constitute a class, or whether class establishes important differences between women, potentially weakening their support for each other. Nicholson does not enter such debates, writing descriptively rather than analytically, but her choice of material demonstrates that the differences between women are as striking as the similarities. Princess Margaret not being allowed to marry the commoner she loved is less distressing to read about than a description of factory workers' fingers being impaled by the needles of their sewing-machines.

Luckily, Nicholson gives us plenty of fascinating stories of non-Royals. Many of them seemed to have more fun than the corseted debs. They could invent their own subversive and glamorous street style, lark about with Teddy Boys, dance to rock'n'roll. They could toe the line in public and rebel in private, as did Constance Spry, the famous flower arranger and founder of the Cordon Bleu Cookery School, who combined marriage with loving her long-term partner, "the cross-dressing flower artist Hannah Gluck".

Nicholson relies on interviews with various women who were young in the fifties, weaving in extracts from memoirs, diaries, journalism and archive material. We hear from women working as air hostesses, housewives, biscuit packers, prostitutes, academics, models, secretaries and Butlins Redcoats. We discover how women felt entering beauty contests, having to give up work on marriage, being defined by their husbands' jobs, becoming unmarried mothers, enduring racism, marching against nuclear weapons, desiring other women.

Nicholson's own commentary, in turns compassionate and wry, holds everything together. She is admirably outspoken about the male-defined, church-defined sexual double standard of the day: "At a time when decent women were expected to be domestic, demure and dependent, their menfolk reacted with bogus outrage as the plumed and painted objects of their deeper desires paraded in the parks and streets… it was the gaudy, visible, threatening streetwalker herself who was not only penalised and outlawed, but beaten up and whipped."

The book is enriched by its notes and bibliography, which make it a valuable resource, sending us off to read memoirs and autobiographies in full. Nicholson is a generous writer, who seems to want to give us everything. Unfortunately, this means that her study is weakened by being overlong. Sometimes she explains and paraphrases too much. Sometimes, speaking for her subjects rather than quoting them directly, she sounds awkwardly novelistic: "It was a few weeks before Valerie permitted Brian the liberty of escorting her back to her house. In due course, convinced that he was 'quite the gentleman', and with the rhythms of the band lending buoyancy to her steps, they set out on the short, lamplit walk back to Nottingham Road. Valerie was glowing. Reaching the gate in the wall, Brian took her in his arms and kissed her there, lingeringly. And then, the gate opened; there to her appalled gaze, stood her mother… The brown eyes that had gazed upon Valerie so meltingly were transfixed with amazement."

The book ends invigoratingly. It sketches Margaret Thatcher's rise in the late 1960s, "systematically demolishing her opponents through the opportunistic manipulation of an obsolete femininity". It describes the opposition in the shape of the future socialist-feminist historian Sheila Rowbotham in Juliette Greco-style black sweater and short skirt and white pancake make-up: "Sheila's voice is a new voice; the voice of the nineteen-sixties: 'We assumed we were going to change the world.'"

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies