Threads: The delicate life of John Craske by Julia Blackburn - book review: An outsider's love of the sea

Blackburn unpicks the threads of Craske’s life and reveals a tangled skein of her own

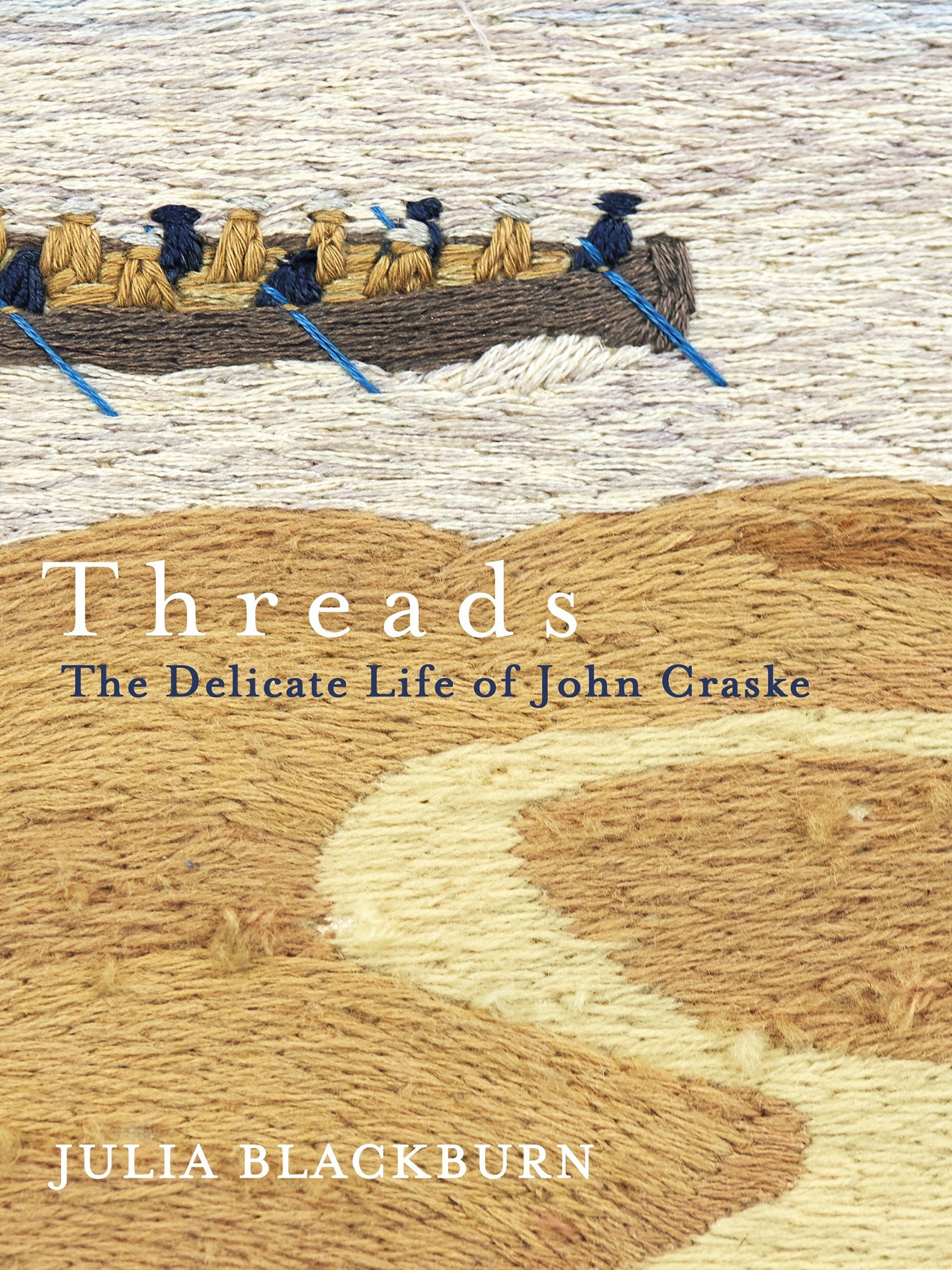

John Craske’s paintings and tapestries have a child-like simplicity, yet they capture the perils of life at sea with remarkable fidelity. It is said Craske worked with the intensity of someone speaking under oath. Outsider artists are fascinating. They lack training and connections, and are often only recognised by chance.

Craske’s life was both poverty stricken and enigmatic. He was born into a fishing family in Norfolk and, after a spell at sea, became a fishmonger. Soon after enlisting in the Army during the Great War, he contracted a strange illness and became lost in mental stupors for weeks and months at a time. After confinement in an asylum he was released into the care of his wife, Laura.

His attempts to resume work failed and the only palliative for his condition was long spells in proximity to the sea. Craske turned to painting and tapestry, invariably depicting boats. He was discovered in 1937 by the poet Valentine Ackland and had a brief period of fashionable success, but afterwards he was largely forgotten.

Julia Blackburn is also something of an outsider. Her approach is very personal and a long way from academic. She chooses subjects trapped in dire straits: Napoleon on St Helena, Daisy Bates in Australian’s desert, Billie Holiday in racist USA and Goya in his deaf old age. As she unpicks the threads of Craske’s life, she reveals a tangled skein of her own. She recounts her visits to archives and interviews with locals, interspersed with stories about herself and her friends.

There are longueurs, but on the whole Blackburn is an engaging enough raconteur and her digressions – covering topics ranging from to Einstein to the Elephant Man - do sometimes help to recreate Craske and his world. The problem is that Blackburn’s extended minutiae come at the expense of a more penetrating and lengthy analysis of Craske’s visionary art. This is a major omission in the book.

What stands out especially from Craske’s life and times is the oddly cloistered nature of fishing communities during the 1920s and 1930s. When tourists started arriving in their villages, the oilskin-clad, sea-booted fisherman appeared alien to them, and their sea-faring lifestyle extraordinary.

Blackburn’s dedication to Craske binds her to him tightly. When tragedy strikes her the solution is the same as it was for her subject, a prolonged immersion in work. As for Craske, the puzzle of his illness remains unsolved, though Blackburn certainly tries hard enough. This wonderfully eccentric biography paints vivid pictures of both artist and biographer. As a bonus, Blackburn is helping to organise a Craske retrospective in Norwich in May.

The exhibition of John Craske’s work opens on 11 May at the Norwich University of the Arts Gallery. It runs until 9 June before it transfers to the Peter Pears Gallery in Aldeburgh, Suffolk

Jonathan Cape £25

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies