The Lost City of Cecil B DeMille: The film about unearthing a 1923 movie set that took 30 years to make

For his original 'The Ten Commandments', DeMille created a ersatz Ancient Egypt 150 miles north of Los Angeles

Buried beneath a windswept sand dune, just outside the small farming town of Guadalupe on the central California coast, there lies a vast, century-old slab of Hollywood history. Now, more than three decades since he first learnt about the site known as “the lost city of Cecil B DeMille”, another film-maker plans finally to bring that history back to the big screen.

In 1982, Peter Brosnan was a 30-year-old freelance journalist and aspiring movie director, who shared a house in Los Angeles with his film-school buddy Bruce Cardozo. One evening, Mr Cardozo told him a scarcely believable story which he claimed to have read in the memoir of the late DeMille, the jodhpur-wearing great-grandfather of the Hollywood blockbuster.

Nowadays, DeMille is best known for his final film, the 1956 epic The Ten Commandments, which stars Charlton Heston as Moses leading the Jews out of Egypt. But the director had also made an earlier version of the same story, with the same title, in 1923. With a budget of almost $1.5m, DeMille’s original Ten Commandments may have been the most expensive movie of the silent era.

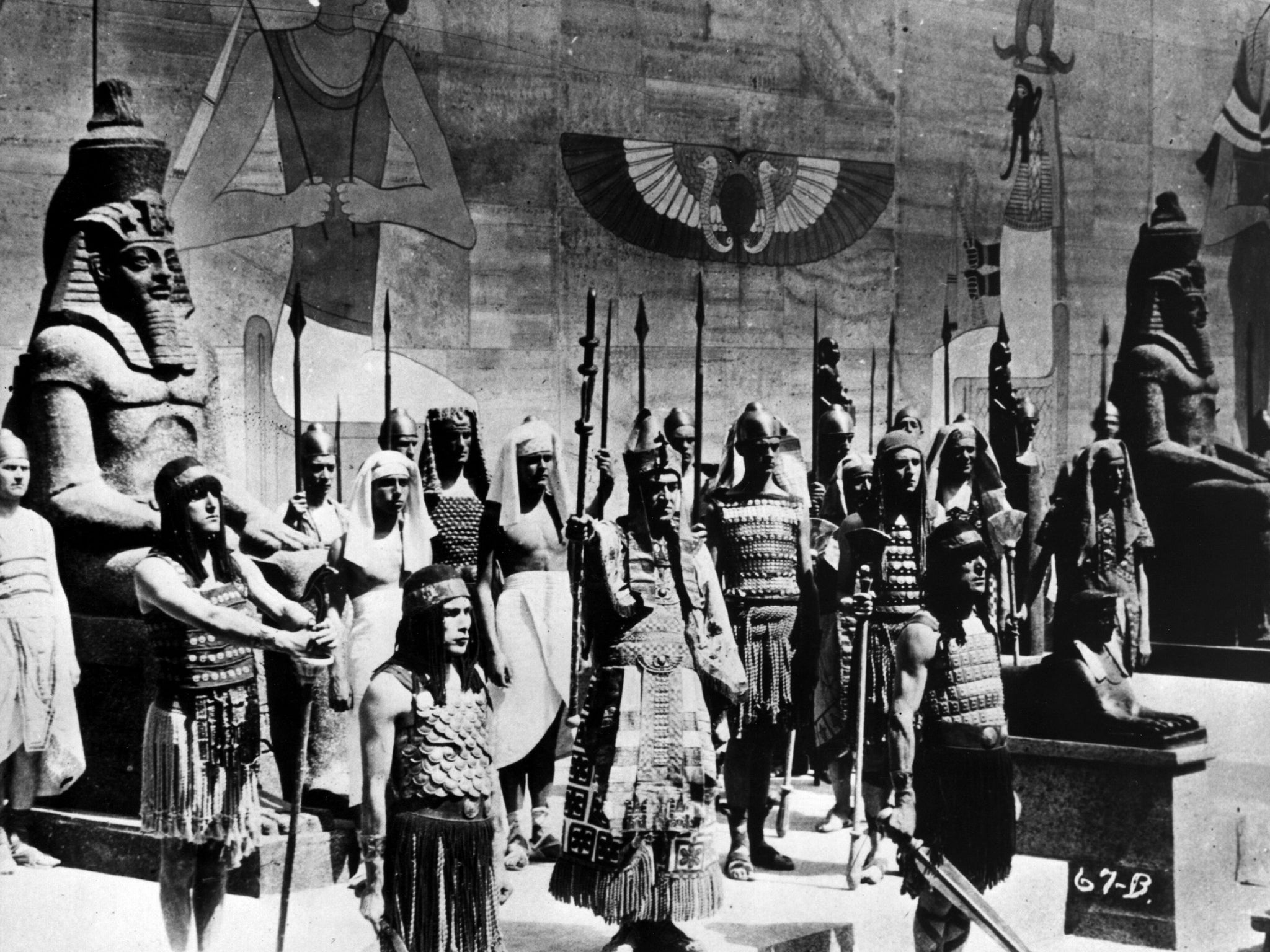

To realise his vision in the days before special effects, DeMille led a cast and crew of 3,500 to the desolate Guadalupe dunes, 150 miles north of Los Angeles, where carpenters crafted an ersatz Ancient Egypt from 168,000 metres of lumber, 11,000kg of nails and 300 tons of plaster. The set was designed by Paul Iribe, one of the founders of the French Art Deco movement, who called for four 40-ton statues of Rameses the Great, eight imposing plaster lions, more than a dozen sphinxes and a 120ft-high backdrop of symbols and hieroglyphs.

When the shoot was complete, rather than dismantle and remove the set, the director ordered it to be knocked down, buried and abandoned to the elements. Mr Cardozo showed Mr Brosnan a passage from DeMille’s posthumously published autobiography: “If, 1,000 years from now, archaeologists happen to dig beneath the sands of Guadalupe, I hope they will not rush into print with the amazing news that Egyptian civilisation ... extended all the way to the Pacific coast of North America.”

Convinced at last, Mr Brosnan drove with Mr Cardozo to Guadalupe, where a local cowboy led them to the site. “We were amazed,” recalls Mr Brosnan, 63. “It happened to be right after the first El Niño winter in California, and a couple of feet of sand had been blown off the dunes. For the first time in 60 years, you could see the statuary sticking out of the ground.”

The friends resolved to make a documentary. “We thought it was such an exciting subject that somebody in the motion picture industry would back us and we’d be done in a couple of years,” Mr Brosnan said. “But it turned into a nightmare.”

For years, against their expectations, they struggled to attract funding. It wasn’t until 1990 that the Bank of America – whose founder, A P Giannini, had been a close friend of DeMille’s – gave them just enough money to conduct a radar survey of the site with archaeologist Dr John Parker. The survey proved that there really was a lost cinematic city preserved beneath the sands.

Suddenly, others were interested: Paramount Studios (which had produced The Ten Commandments) wanted to back the documentary. Television stations wanted to broadcast it. But just as Dr Parker prepared to start the excavation and Mr Brosnan prepared to shoot it, Santa Barbara County denied them permission to dig at the site, which is part of a national wildlife refuge.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Rather than tread water, the filmmakers interviewed anyone who had worked on the film or known DeMille, including the director’s niece, Agnes DeMille, who died shortly afterwards, in 1993. But by the time the necessary permits were secured two years later, the top brass at Paramount and Bank of America had moved on, and Mr Brosnan’s funding for the dig had dried up.

During the 1920s, the Guadalupe dunes often stood in for the Middle East, in movies including The Thief of Bagdad, The Sheik and its sequel, The Son of the Sheik. “After World War One, people were more familiar with that part of the world,” said Doug Jenzen, executive director of the Dunes Centre in Guadelupe. “There was the new demand for Middle Eastern oil as cars became more common.” The discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922 also captured the imagination of the public.

Before work began on The Ten Commandments, DeMille warned his cast they would have to endure “perhaps the most unpleasant location in cinema history”. It was worth it: the film grossed $4m – spectacular by 1923 standards – and DeMille’s images set a template for generations of blockbusters to come. The parting of the Red Sea in 1923 looks much as it did in 1956 or in Ridley Scott’s recent Exodus: Gods and Kings. The effects may have changed, but the effect is the same.

With his documentary project on indefinite hiatus, Mr Brosnan wrote screenplays, many of which were optioned, few of which were produced. Eventually, he tired of showbusiness and retrained as a psychotherapist, working on child abuse investigations for LA County, which he does to this day. A rough cut of the film sat in his garage. “I never looked back at the film industry,” he said, “except for this one project that just would not go away.”

Every so often, a reporter would call to ask whether the project had progressed, and Mr Brosnan would be forced to disappoint them – until 2010, when a piece in the LA Times caught the eye of a wealthy private donor in Texas, who offered him funding to excavate a sphinx and complete the film. “My first reaction was panic,” Mr Brosnan said. “In 1990 I was a single, freelance writer and I could take three months off for a project. But now I’ve been working for LA County for 20 years. I have a wife and two kids! I thought, ‘There’s no way I can do this.’”

Mr Brosnan asked a producer friend to help him finish the documentary. Once again, the dig ran into permit trouble.

But in 2012, at long last, a camera crew was on hand as the archaeological firm Applied Earthworks excavated one of DeMille’s sphinxes. The sequence will make up the finale of the film, while the sphinx fragments are now on display at the Dunes Centre, alongside other items recovered from the sand, such as fake ancient coins, the remnants of a box of Eastman Kodak celluloid and several bottles of cough medicine: the preferred tipple of the Prohibition era.

“In this country we’ve saved very little of our motion picture heritage,” Mr Brosnan said.

Greatest film quotes of all-time

Show all 10“Half of the movies made before 1950 don’t exist any more. Ninety-five per cent of the silent films made in the US are gone.

“As for artefacts from that era, there’s almost nothing. But DeMille buried enough in the Guadalupe dunes to fill several museums.”

Mr Jenzen and Mr Brosnan both say they hope the discovery will bring more tourism to Guadalupe, a poor agricultural community with a per capita income of only $13,000 (£8,600). The town’s only cinema was boarded up long ago. But the number of visitors to the tiny Dunes Centre, drawn by the publicity around the DeMille project, has grown “exponentially” in recent years, said Mr Jenzen.

Bruce Cardozo, whose discovery of that fateful paragraph first set the project in motion, and who shot many of the original interviews for the documentary, remained in the film industry, working in visual effects for movies including Captain America and The Avengers. Sadly, he died unexpectedly several months ago, just before the film’s final cut was completed.

More than 30 years in the making – or more than 90 years, depending on your perspective – Brosnan’s film, The Lost City of Cecil B DeMille, is now being submitted to film festivals. “We got a sphinx out of the ground,” he said, “and this chapter of my life is finally finished.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies