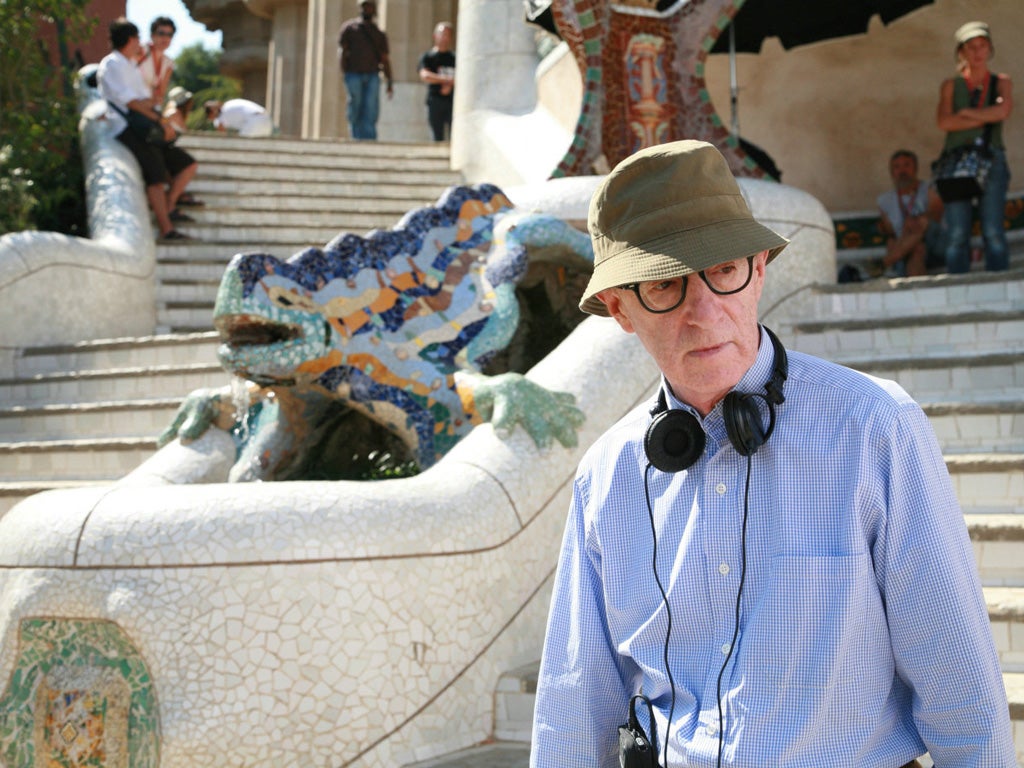

Woody Allen: A New Yorker's state of mind

A Woody Allen retrospective begins this month at the BFI and promises to be a treat for his fans. But he still regrets never a having made 'a great film', as a new documentary reveals.

The 76-year-old man revisits the haunts of his youth. We see him outside the decrepit old Brooklyn cinema where, half a century ago, he came to see his first Ingmar Bergman movies. He is shown in the grounds of the high school where he had such a wretched time. Faces from his earlier years flit in front of the camera: girlfriends, collaborators, his devoted younger sister Letty and even – in archive footage – his sharp-tongued mother Nettie reminding him of what a demanding kid he once was. Archive footage rekindles memories of his boyhood trips to Coney Island.

The man in question is the comedian and filmmaker Woody Allen. You can't help but be reminded of Bergman's Wild Strawberries (1957) by the new film about Allen made by Robert B Weide (director of Curb Your Enthusiasm and one of Allen's most fervent admirers.)

Just as in Bergman's celebrated feature, a distinguished figure in the twilight of his career confronts his own past. Like the old professor played by Victor Sjöström in Bergman's film, Allen can't disguise his disappointments or his yearnings. Even after 40 years, he is still fretting over the "essential triviality" of his early movies and striving "to make a great film, which has eluded me over the decades". He is also worrying about his own mortality – a preoccupation that took hold of him when he was five years old. Nor has that dream of becoming a great jazz musician like his idol Sidney Bechet ever dissipated.

We all know how reticent Woody is. You don't expect him to open up about the implosion of his relationship with his one-time muse Mia Farrow or to talk about his step-daughter-turned-wife Soon-Yi. The tone of Weide's film is reverent, even hagiographical. Nonetheless, it is unexpectedly revealing about its subject. We see Woody sitting at his desk in front of the ancient but still immaculately preserved German portable typewriter he has used throughout his working life. Like a boy scout, he uses scissors and staples to knit his articles and screenplays together. We see him rummaging in the bedside drawer in which he keeps his huge treasure trove of sketches and storylines for possible future films.

Woody Allen: a Documentary is likely to surface in Britain next year. In the meantime, the BFI Southbank is holding a retrospective of Allen's work. As this season underlines, Allen is a full-blown phenomenon – easily the most prolific A-list film-maker of his era. Not only has he made close to 50 movies. He has also retained complete creative control over all of them, a near miraculous achievement given the changing tastes of audiences and the demands of financiers.

It is startling how little Allen has changed in the last half century. He was still at school when he started selling jokes to the newspapers. He "became" Woody Allen because he didn't want his classmates to see his real name in the Broadway columns of the newspapers. Born Allen Stewart Konigsberg, he metamorphosed into the comedian we still know today. Those trademark spectacles were adopted early too. He started wearing them because a comedian he admired – Mike Merrick – had a pair. He thought they gave him a comic gravitas. The persona was put in place by the time he was 20 and it has hardly changed since.

The paradox of Allen is that he wants to struggle with the metaphysical monstrosity of existence but has never been quite able to. He talks in Weide's doc of why he puts a higher value on the tragic muse than on the comic muse. What is painfully evident is that he has never really been open to this tragic muse. The ferocious work ethic that made him so successful so early meant that he was invariably so busy with the next project that he had no time to dwell on the last one. He never looks back. He doesn't watch his own films again. He doesn't read reviews. Although his movies are famous for the way they probe into the inner lives and anxieties of his characters, there is little evidence that he agonizes over his own life in the same way. The neurosis is all on screen. His friends all describe about how good he is at "compartmentalizing". A former wife mentions in wonderment how well he sleeps. Even when his custody trial with Mia Farrow was the subject of garish news headlines all over the world, he carried on working as normal.

Allen claims to be influenced in equal measure by Groucho Marx, Bob Hope and by Bergman. He was first lured to Bergman's Summer with Monika by publicity promising that the film's star, Harriet Andersson, would disrobe. "She was allegedly naked in that film so I beat a quick path to the door and I went to see that film just so I could see a woman without her clothes on and it was a fabulous movie apart from the nudity," he tells Weide.

After watching Harriet Andersson gambolling naked in the Swedish countryside, Allen soon discovered other Bergman movies like The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

"I thought it's pointless for me to work any more because no one will ever be able to do anything better than this. Bergman has just reached the limit of what you can do in film and there was nowhere else to go."

Not that the shadow cast by Bergman stymied him in any way. One ruse he seems to have learned from the Swedish master was always to have the next project in place. That meant you would never be distracted by the success or failure of the current film but could keep on working regardless.

"I don't do any preparations," Allen admits to Weide in what can't help but seem like a shocking confession. "I don't do any rehearsals. Most of the time, I don't even know what we're going to shoot when they hand me the couple of pages of material that we are going to do for the day and I see what I am in for. I don't read the script. After I am finished with it and rewrite it, I don't read it again because it gets stale to me and I start to hate it." This explains why the films are so fresh but also arguably why the lesser ones seem so perfunctory.

The irony is that Allen became a film-maker in the first place because he was a perfectionist. The comedian was unhappy with the way Hollywood "mangled" his first feature film script, What's New Pussycat, directed by Clive Donner. Allen knew he could do far better himself and was determined to protect his material.

Allen's Peter Pan-like qualities were underlined when his most recent feature Midnight in Paris became his most successful ever at the US box-office. Even without the $50 million and counting that his 47th feature has already made, there are many potential patrons who would rush to finance his work. As the years pass, it seems less likely that he'll ever make that one truly "great" film that he talks about. The irony is that if he ever did, he'd almost certainly find fault with it... and the audience would still probably prefer the earlier funny ones anyway.

BFI Southbank's Woody Allen retrospective (media partner: The Independent) runs from 30 December to the end of January

Funny Guy: The best Woody Allen Films

1. Manhattan

Gorgeously shot in black and white by the "prince of darkness" Gordon Willis, full of Gershwin music, this is Woody at his most rhapsodic and romantic.

2. Broadway Danny Rose

Woody in Damon Runyon mode as a small-time theatrical agent. Mia Farrow gives one of her best and

least characteristic performances as a gangster's moll.

3. Crimes and Misdemeanours

Woody poses some profound questions about love, death and conscience without ever losing his comic zip.

4. A Midsummer Night's Sex Comedy

The mood is akin to that of 'Smiles of a Summer Night' in Woody's magical country house comedy drama.

5. Zelig

A technical tour de force, this spoof doc tells the story of a human chameleon who popped up at every key moment of the 20th century. The presence of heavyweight talking heads like Susan Sontag and Saul Bellow adds an air of verisimilitude. Did Leonard Zelig really exist?

6. Love and Death

Tolstoy done Groucho Marx-style in Allen's high-spirited foray into the Russian epic genre.

7. Hannah and Her Sisters

Allen complained that the film was too "optimistic" but this Chekhovian drama about three unhappy sisters in New York is one of his best observed.

8. Annie Hall

Diane Keaton was the perfect foil for Allen, a preppy girl about town, as outgoing as Alvy Singer (his character) is neurotic.

9. The Purple Rose of Cairo

Allen's escapist Depression-era fable sees matinee idol Jeff Daniels step out of the screen and into the life of housewife Mia Farrow.

10. Bullets Over Broadway

This Roaring-Twenties-set comedy is a delight, even if Chazz Palminteri's gangster-writer seems far-fetched.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies