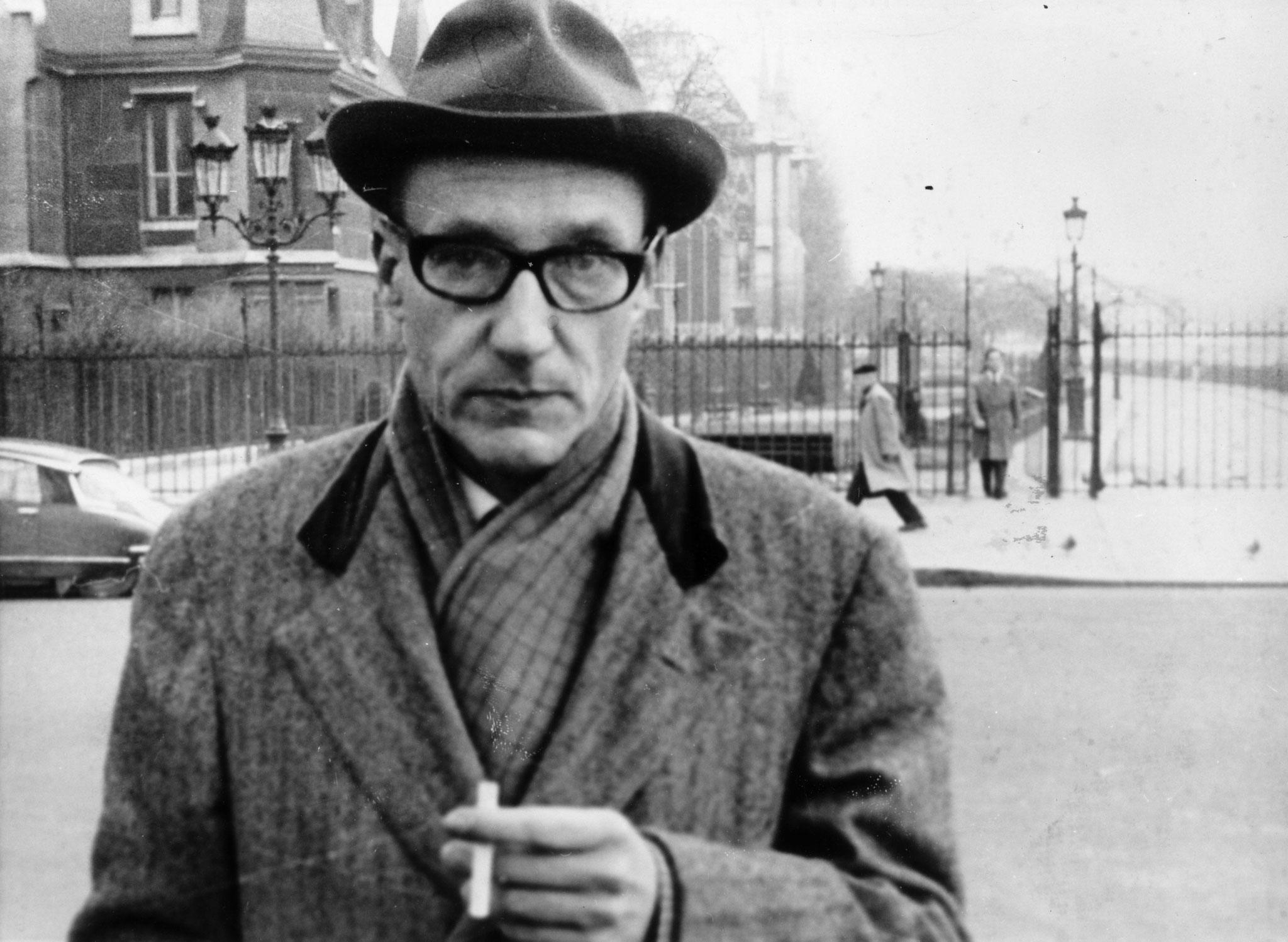

Burroughs: The Movie: Not just looking back at the life of William S Burroughs, but also 80s New York

One of the most intimate and intriguing portraits of the iconic author

Made in 1983, Burroughs: The Movie is one of the most intimate and intriguing portraits of the iconic author. Filmed over the course of five years, the documentary follows William Seward Burroughs as the Beat writer makes television appearances, walks around New York reminiscing about his youth and features Allen Ginsberg, Herbert Huncke, Patti Smith, Francis Bacon (the painter) and Terry Southern. This is no hagiography, with Burroughs captured at his inimitable best and cranky worst.

Howard Brookner started on the documentary as part of his New York University thesis project. He employed his classmates, Jim Jarmusch as the sound recordist and Tom DiCillo as cameraman. For many years the film was considered lost as there was not a single celluloid copy of the film in circulation. A few people owned Burroughs on videocassette, from which snippets of footage had made their way onto YouTube.

Things would have remained that way, were it not for the imagination, pride and dreams of a young boy. Aaron Brookner was just 7-years-old when his uncle Howard died, aged 34, in 1989. The director would also make a documentary on opera director Robert Wilson, titled Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars, as well as roaring twenties comedy Bloodhounds of Broadway starring Madonna and Matt Dillon. Howard Brookner died, having contracted AIDS, before Bloodhounds of Broadway was premiered at the Cannes Film Festival.

Visiting the set of Bloodhounds was one of Aaron’s earliest memories, one that had a profound impact on him. “There had always been these sharp memories about my uncle, sharper than most memories, I didn’t really know why,” says Brookner. “Then when I started looking for footage, one of the things that I came across were these home videos, and a lot of it featured moments where I’m videotaping him, and anyone who has shot something with a video camera will note that the act of doing that will really focus your mind.”

Amongst the items that Howard left after he died were the sound rolls that were attached to the magnetic film rolls. These amounted to 30 hours of recordings, including from the Nova Convention of 1978, which was three days of discussions, screenings and readings, revolving around the extraordinary work of Burroughs. The writer had the ability to be a master of so many forms, hard-boiled fiction, memoir, nonrepresentational writing, letters, satire and tales of his drug taking. Burroughs writings on yagé have even been used as part of the ongoing research into Parkinson’s disease.

So Brookner set about seeing if he could discover his own Holy Grail – the celluloid strips that would match the sound recordings. His dream was to see a copy of Burroughs: The Movie that would allow the audience to appreciate the artistry of the filmmaking, as much as the wiles of the subject. Brookner’s last hope was that the film canisters would be in The Bunker, the studio on the Bowery in New York that Burroughs worked in. Brookner made several attempts to be allowed entry. Then one day, he hit the jackpot, and he recorded the moment, which appears at the start of a film that he’s made on Howard Brookner’s life, called Uncle Howard.

Walking into The Bunker, he was shocked to see that nothing had changed since the time the film was made. The office is next to a former YMCA and swimming pool, so the walls are incredibly thick, blocking out the noise from the busy New York street. On the rack were spices dated from 1978, a handgun still slept in Burroughs’ dresser, and on the shelf were the film canisters with 30 years of dust.

“There is a great line in the Burroughs doc my uncle made where Burroughs talks about time travelling. He says it’s not possible,” reports Brookner. “Going into the bunker was like time travel. I couldn’t touch anything but suddenly I was plummeted into this whole other planet.”

Brookner describes the feeling as being like inside Burroughs’ The Western Land (1987), the final book of a trilogy containing Cities of the Red Night (1981) and The Place of the Dead Roads (1983). The title is about the western bank of the Nile river, which in Egyptian mythology is the land of the dead. “This space has that vibe to it, it feels to me like his own sort of Egyptian myth. That is the writings and talks on the soul, the different aspects of the soul, so that is what I experienced.”

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

The canisters were remarkably well preserved, and Brookner searched a partner who could help him restore the footage to their former glory. He worked closely with the fabled American home entertainment label Criterion to do so. But Brookner’s interest in bringing the 1983 documentary back into circulation for a new audience was fuelled as much by his desire to reappraise his uncle, more than just to add to the plethora of information on Burroughs.

“Going into it, I felt a sense of injustice because Howard was taken from us very young and in such a dramatic fashion,” says Brookner. “I don’t think there was a time for people to appreciate what he had done as a filmmaker and now it’s becoming more apparent, especially with Uncle Howard.”

Uncle Howard pits Brookner at the vanguard of the American independent scene that dominated much of 80s and 90s cinema. In addition to Jarmusch and DiCillo, Brookner’s contemporaries including Spike Lee and Sara Driver. At the time, Brookner was seen as the leading light, the one that Cannes had their eye on, and movie stars flocked to work with. One can only wonder what films he would have made, had he lived.

The film Brookner has made is another window back into the time period, but this time with the perspective on the next generation, who looked to cinema rather than writing to tell stories. It’s also the story of how the AIDS epidemic took a dagger to the New York art scene and the gay scene in the city.

Brookner sees the two films as companion pieces, which are not necessarily needed to be seen together. “I think that people who are into Burroughs and the film will love Uncle Howard. I have had lots of people who know nothing about Burroughs that have walked away with a lot from Uncle Howard. In a way they are similar because Burroughs is about Burroughs but also about the time in New York and what is going on and my film, if you will, is about New York, but it goes deeper and beyond as it’s about the whole of the 80s.”

Burroughs is available on Blu-ray now on The Criterion Collection

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies