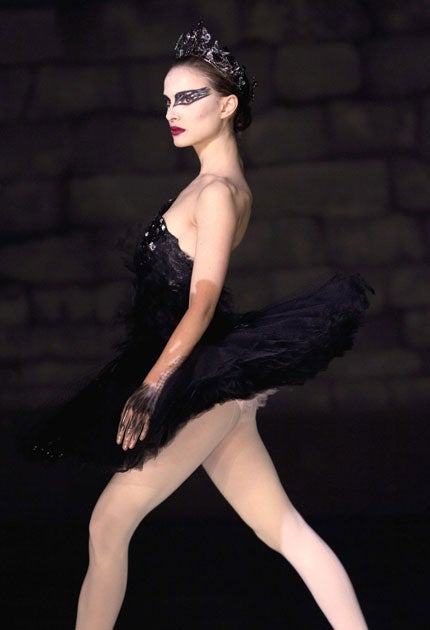

Black Swan: Caught in the dance

Black Swan shows ballerinas as obsessive, mysterious creatures. We do the artform a disservice with this much-peddled myth, says ex-dancer Alice-Azania Jarvis

Tortured by her art, obsessed with achieving total perfection, Natalie Portman's starring role in Darren Aronofsky's Black Swan follows faithfully the traditions of dance cinema. Rarely is a ballerina shown happy, or well-balanced. Abnormal in her abilities, designed to perform, the fictional ballerina is an exotic creature – a beautiful freak, someone observed and admired, but not, necessarily, understood.

This isn't surprising. Ballet occupies a peculiar position in the public consciousness. For centuries, it has persisted as a subject of fascination, inspiring impressionist portraits and Hollywood films, drawing crowds to the world's biggest opera houses and concert halls. Yet, as art, it remains oddly inaccessible in a way that few other disciplines manage. Those who regularly attend the ballet are a select group; there is a distinct whiff of the hoity-toity among their numbers. To outsiders the mechanics, the sheer plausibility, of what dancers do remain inscrutable – like watching a sport whose rules you don't understand. Painting, photography, installation, literature – even film and music – have all crept into the realms of do-ability. Be it the popular scepticism which greets the Turner Prize each year, the blogs and digital cameras that allow us all to be writers and photographers, or the televised talent contests promising anyone a shot at stardom, few creative disciplines remain out of reach. But ballet does. The jetés, the pirouettes – even the simplest of arabesques – will always be well beyond the physical abilities of the average spectator. They require not just decades of training and vast reserves of self-discipline, but also a talent of the highest order.

I can't remember my first ballet class. I was, after all, only two. Probably my first flash of recollection, my first real memory, was of my primary exam. Not the actual process, of course; body rigid with fear, mind blank with terror, the oh-so-brief encounter with a ballet examiner, rarely lingers in the mind. What stays with me is the disappointment. “Merit,” my resulting certificate said. It wasn't a bad outcome; certainly, it was better than a paltry pass or shameful fail – but it wasn't a distinction. Only one girl in our church hall troupe received that coveted grade. It was my first taste of mediocrity, a quality which both dominated the remainder of my 17 – 17! – years in training, and which, with curmudgeonly, dream-crushing inevitability, removed all possibility of ballet becoming anything other than a hobby.

Ask a ballerina what is wrong with them and prepare for an encyclopaedia of complaints. Shoulders were my undoing. “Relax your shoulders” – God, what an irritating phrase. “They are relaxed,” I would repeat, week after week, year after year. And I was right: they were. But I was also wrong, or at least my physique was. The Jarvis high shoulders had no place in a tutu. Likewise my turn-out – my hips, unsupple despite years of stretching, could never quite execute the perfect right angles required – and my inward-rolling soles, which threatened to ruin every plié. At least I was thin, and that counted for quite a lot. No tragedy was quite so great as the talented girl who, aged 14, metamorphosed into a talented lump, provoking weekly dietary interrogation from Madame and frequent, pointed instruction to “suck that stomach in!”

Physical perfection is the altar at which the ballet world worships. Dancers must combine extreme athleticism with strength, poise, balance, and grace. Every muscle is conditioned, the feet subjected to famous humiliation. Last month, when the New York City Ballet sent Jenifer Ringer on stage looking slightly rounder than the sinewy, honed ideal, the dance critic Alastair Macaulay penned a scathing review for The New York Times. Had she, he pondered, swallowed “one sugarplum too many?”

Achieving such heights is no mean feat. Although there are exceptions, most professional dancers will have started their training by the age of five. The Royal Ballet School (RBS) takes students from aged 11 and upwards; of the 1,000-odd devotees in the running for a place, just 25 will get one. From that point on, the would-be performers are constantly assessed. “If a child isn't displaying all the qualities required, we will sit down with the parents and try to find an alternative,” explains Jim Fletcher, development manager at the school. Options range from other ballet schools to performing arts colleges, or even mainstream education. When the students are 15, the ante is upped even further as an influx of talent from across the globe competes for access to the prestigious secondary school. Half of the primary school's youngsters will make the leap, and half will be forced to look elsewhere. Those who remain continue in their balletic immersion: sharing dorms, getting early nights, dividing their day between dance and academics.

The result is the notion of ballet as we perceive it, as it is portrayed in the high-drama pantomime of Aronofsky's creation. Ceaselessly competitive, brutally perfectionist, relentlessly scrutinised, the imagined life of the ballet dancer bears little resemblance to most humdrum human existence. This, of course, accounts in large part for our fascination with it; the sheer exoticism of the ballet lifestyle props up the idea of the dancer as a glamorous curiosity. Coupled with the allure of life in the spotlight – or at least life on the stage – it is precisely this pedestal's construction which, says Alistair Spalding, artistic director of Sadler's Wells, leaves us ordinary folk so enamoured of the dance form: “It is an intoxicating concept. Ballerinas are exceptionally elegant, and very well-poised – and, for the most part, they lead elegant lives.”

Yet ballet is not quite the ivory tower it once was. True, it has still to attract the kind of mass audience of other dance forms – ballroom or breakdance, for instance. Tickets to the classics may still be restricted to those willing to spend as much as a short-haul flight on securing a seat. Onstage, the picture is rather different. Dancing ballet – once a decidedly genteel pursuit – is now an option open to those from a diversity of backgrounds. Some 46 per cent of the RBS intake comes from households with a total income of £30,000 or less. And while girls have, historically, outnumbered boys seven to three, admission of the two sexes is now equal. “Billy Elliot did more to sort out that bias than anything,” says Jeanetta Laurence, associate director of the Royal Ballet. The quest for the very best, meanwhile, means that the leading international dance companies are more likely to be dominated by foreign-born talents than the privileged few of Margot Fonteyn's day.

This democratisation can only be a good thing. Elsewhere, a debate rages over how far the reality check should be extended. Recent attempts to attract a wider audience through targeted ticket offers and backstage open days have prompted the predictable objections over “dumbing-down”. And, while some dancers have complained of the sensationalist stereotyping they fall victim to, there is much to be said in favour of disguising more mundane truths. After all, much of what dancers do is based on deception. They manipulate their bodies in weird ways, they use their hard-won technique to create physical illusions, and they don costumes to give specific impressions. When it comes to the spectacle, maintaining popular prejudices may be no bad thing. If the mystique that the dancers bring, the sense of drama offstage as well as on-, is a key component of ballet's appeal – then it would, surely, be an unfortunate one to let go of.

“It is one of the hardest things to deal with,” Laurence agrees. “We reached a point where we had to make this difficult decision: do we break the myth? If you let people see the underbelly, are you destroying the appeal?” Over the years, Laurence says, they have “let down the drawbridge somewhat”, inviting audiences to engage with the company's stars while resisting the temptation to embrace all-out populism. The result has been a steady increase in attendance figures: these days, Royal Ballet occupancy sits at around 90 per cent.

But it isn't just the Royal Ballet that is doing well. Indeed, all the evidence suggests that our interest in ballet is growing. Not only do we have two major ballet blockbusters to look forward to – Black Swan, yes, but also The Adjustment Bureau, a George Nolfi-directed thriller in which Emily Blunt stars opposite Matt Damon as an English ballerina living in New York – but a series of dance spectaculars promise to dominate next year's cultural calendar. In June, the Cuban ballet megastar that is Carlos Acosta will appear at the O2 Arena performing Romeo and Juliet before some 23,000 anticipated visitors. In March, the Pet Shop Boys will score a new ballet from Venezuelan choreographer Javier de Frutos. In the meantime, Sadler's Wells has increased its audience by 56 per cent, and the English National Ballet's annual Nutcracker looks likely to sell out.

Still, a creative crisis is thought, by some, to have taken hold. Granta recently published Apollo's Angels: A History of Ballet by Jennifer Homans. Homans is a vociferous critic of the state of the discipline, and has argued that ballet as a creative force is at risk of dying. According to this view, both the choreographers and ballet dancers have failed to live up to the legacy of their predecessors. The result is an international repertoire of little variation, in which the classics – such as Swan Lake, The Nutcracker, Giselle and Sleeping Beauty – are revisited time and time again. Not everyone agrees that this is the case – Laurence is firm in her insistence that not only is “new work selling better than ever before” but that the Royal Ballet is succeeding in its attempts to push forward. Spalding, though, is less sure. “There are exceptions, of course,” he says. “But there isn't a sense of creativity happening. We need to create the classics of tomorrow. Works that, in 100 years' time, people will still be enjoying.”

Towards the end of my time at the barre, I was doing little more than going through the motions. My priority had long before shifted towards academics, the five-night-a-week schedule demanded by my ballet teacher written off as an impossibility. While the girls around me (there were only four of us, aged 18, still plugging away) planned lives as dance teachers, I fell further and further behind, toppling midway through once-simple pirouettes, the childhood nostalgia of the studio exerting less and less of a hold. Ballet isn't really a hobby; it's far too difficult for that. Even after all those years, almost two decades of dedication, the abilities of the real talents remained well beyond my reach. And so now I go, like every other non-dancer, and gawp at the spectacle of the principals and the splendour of the corps, tear up at the lusciousness of the scores and marvel at the twinkling of the costumes. Who knows quite what goes on when the curtain comes down, quite what melodrama unfolds in the backstage labyrinth; though for those brief few hours that the curtain is up, our fascination with ballet isn't hard to fathom at all. Not in the slightest.

To win VIP tickets to 'The Nutcracker', visit http://ind.pn/fvtcqC

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies