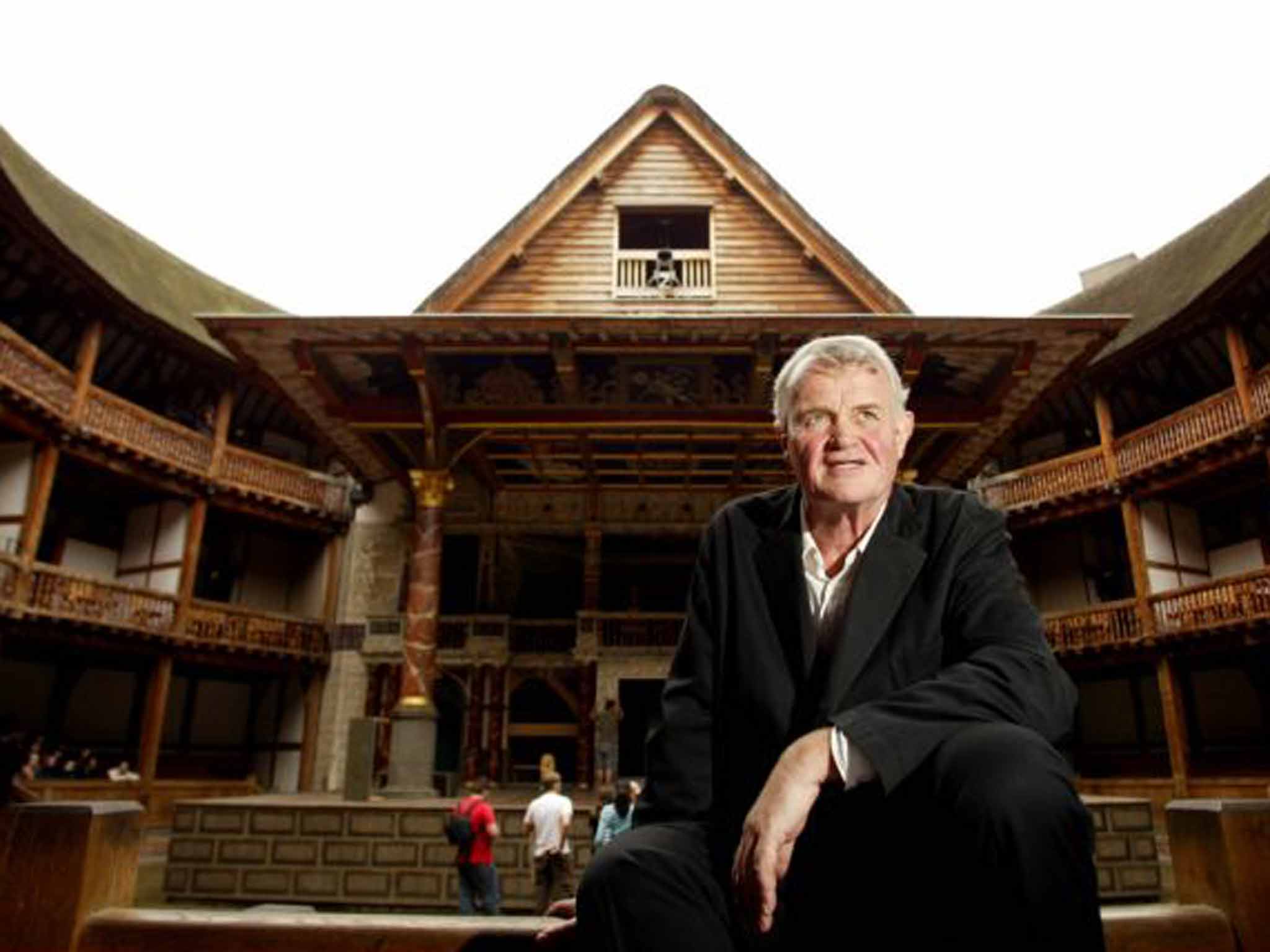

Howard Brenton on 'Doctor Scroggy's War' and an arena of opportunity

With his First World War drama opening at the Globe in two days, Howard Brenton explains why this intimate, bare-staged amphitheatre provides the perfect setting for a storyteller to awaken an audience's collective imagination

For a playwright, Shakespeare's Globe is the most experimental theatre in the country and not at all the dead, heritage, "merrie England" theme park which the more snooty members of the British theatrical establishment thought it would be. Writing for it concentrates the mind wonderfully; it puts, if not the fear of God, certainly the fear of Will into you. I have sometimes sensed an angry bald ghost in the upper gallery looking down on rehearsals muttering about my efforts: "I beg, thou scribbler, cut!"

Doctor Scroggy's War was commissioned by the Globe and is the third play of mine to be premiered there. It is set in the First World War and is about a young lower-middle-class soldier, Jack Twigg, and an aristocratic woman, Penelope Wedgwood, who falls in love with him. His father is a ship's chandler with a business on the north bank of the Thames. Jack is bright and has a love of military history – as a boy he fought the battle of Waterloo with toy soldiers on the parlour floor. He makes it out of his class through education and gets a scholarship to Oxford. His parents have high hopes for him – hopes that are dashed when war breaks out and Jack enlists as a lieutenant.

He is a figure that fascinates me: the intellectual at war. But the army is not easy for Jack. He is a "temporary gentleman" – an officer, but from the lower classes. He has to struggle to get to the front, and when he does he lasts a few seconds before receiving a terrible injury to his face. The play then dramatises his recovery as the patient of the extraordinary polymath and brilliant surgeon Harold Gillies, acknowledged as the father of modern plastic surgery.

Jack and Penelope are my inventions. They meet on a mad night at the Ritz. From then on their lives are incident-packed and twisty, set in ballrooms, battlefields, hospital wards and gardens. And here the Globe helps so much because it is a great theatre for story telling: it blazes out narrative to the audience. Of course, Shakespeare exploited this with consummate skill: the short scenes in Antony and Cleopatra can bog the play down in a conventional theatre, but at the Globe they pile up a dizzying pressure of political narrative, flitting between Rome and Alexandria. An actor can swing round a stage pillar and say: "The other side of the world," and the a udience immediately says to itself, fine, we're on the other side of the world. … Why painting scenes with words at the Globe should be so strong is a mystery. It may have something to do with the powerful presence of the building itself; you can dress the stage but not change it; there are no sets, no projections, no lighting effects, just the collective imagination of the audience to awaken with words. "Think when we talk of horses, that you see them …" says the Prologue in Henry V. And in the yard and the galleries, you do.

What helped me in dramatising Harold Gillies were accounts of his extraordinary way of speaking. He was renowned for being difficult to understand, flinging out sentences studded with bizarre metaphors, speeding ahead of his listeners and, at times, himself. Gillies had a hyperactive sense of humour: there were practical jokes and entertainments; there was cross-dressing and illicit champagne and oysters served at night in the wards. Queens was a military hospital and rumours of "goings on" troubled authority. But Gillies, who treated more than five thousand terribly wounded men, some needing as many as 50 operations, understood that souls as well as faces had to be healed. Some of his patients never reintegrated into society but an extraordinary number did, with an insouciance that Gillies's "goings on" encouraged. I have him say about the hospital "We don't do glum here" – that was his spirit. But he was also conflicted in his work by a great fear: that the men he healed would go back to fight at the front.

The audience at the Globe is very powerful. They are relaxed; they can see each other; there is none of the "going to church" hush you get in a conventional theatre. The communality of the wooden O – in rain as well as in sunshine – puts them in a good mood. The theatre has something of Joan Littlewood's dream of a fun palace: it encourages laughter, big waves of it, which can be glorious. But over the years we who have worked there have discovered that it is far more than a venue for knockabout. With asides and soliloquies from its stage, actors can open the minds of characters directly to the audience. The Globe is a sophisticated instrument, able to deliver extremes of comedy and tragedy almost simultaneously and with great psychological complexity. It is, after all, a Renaissance building, part of the movement that established our modern sense of humanity.

So in writing my "war play" for the Globe's stage I've tried to use its powers to dramatise Harold Gillies' complex but life-affirming spirit and his struggle with a secret that men keep to themselves about going to war: we love it.

'Doctor Scroggy's War' (0207 401 9919; shakespearesglobe.com) Friday to 10 October

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies