Javier de Frutos: 'Destroying art? It's like slapping a nun...'

After boos, death threats and a breakdown, the enfant terrible of dance returns – this time with a three-act ballet scored by the Pet Shop Boys

What do you do when your last major show has been drowned out by boos from the stalls, called "ill-conceived and barkingly offensive" by the critics, and banned by the BBC? How do you return to work when – because of that scandal – death threats have been left on your phone, you've been hospitalised with a nervous breakdown, and spent a year unemployed?

Some artists might slip back under the radar – but that's not where choreographer Javier de Frutos has ever felt at home. For his first outing since 2009's Eternal Damnation to Sancho and Sanchez – think deformed popes, pregnant nuns and wild sex, live on stage at Sadler's Wells – De Frutos returns with one of the dance events of the year. It's a new three-act ballet, it's scored by the Pet Shop Boys, inset left, and its title is pure De Frutos. The Most Incredible Thing opens this week.

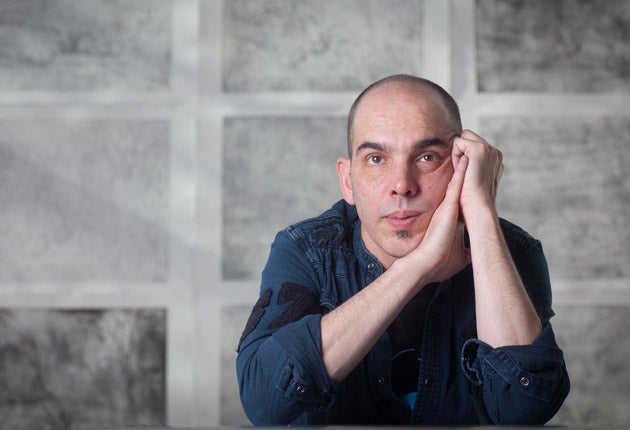

What's instantly clear, when I meet the Venezuelan at his east London rehearsal rooms, is that the scandal hasn't silenced him. Some interviews are blood out of a stone; this one's blood out of an open wound. He's frank about the pressure he feels as his new show looms. He squares up to his accusers, including "that bitch" of a critic (unnamed, mercifully) who ring-led the boos at Sadler's Wells. And he's painfully direct about the lovelessness, insecurity and intimations of mortality afflicting him at only 48 years old. Early in our conversation, De Frutos cites the playwright Tennessee Williams as his personal "most incredible thing", and by the end of it, he's turning into a one-man, twinkle-toed Blanche DuBois.

Like Blanche, he was once young and wild. De Frutos's early notoriety derived from his habit of dancing naked – "his bobbling penis," wrote one critic, "provided a whole new interpretation to the strippers' number from Gypsy" – and from erotically charged, blood-soaked productions such as Transatlantic and Grass. The establishment embrace was proffered with Olivier award nods for Milagros, with the New Zealand Ballet, and Elsa Canasta, with Rambert. Later, De Frutos choreographed the musical Cabaret in the West End and Carousel at – an unlikely home for an enfant terrible – Chichester Festival Theatre. So he dismisses doubts that a man with his reputation should now be helming a "family show" such as The Most Incredible Thing. "It's bollocks," he says. "As an artist I have the capability of doing anything."

The show is based on a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale about a contest to produce an incredible thing, and by doing so, to win a princess's hand in marriage. The subject has prompted De Frutos and his dancers to reflect on their own "incredible things", he tells me. Tennessee Williams is one; so too is De Frutos's memory of "my dad bringing our first colour TV home, on which even the ads were absolutely fascinating." In the Andersen original, our hero creates a beautiful clock, and wins the prize – only to see it pulverised by a rival. "And that act of destroying the most incredible thing itself becomes the most incredible thing," says De Frutos.

"But, as [Pet Shop Boy] Neil Tennant said the other day, you can destroy the object but you can't eliminate the idea." To De Frutos, his show is about the ineffable potency of art. "The power of destroying art is enormous. It's like slapping a nun," says De Frutos, who – judging by his recent output, knows whereof he speaks. "Art is incredibly powerful and we're still shocked when somebody runs into a gallery and slashes a painting." He doesn't greatly identify with the romantic element of Andersen's story, because "I'm not in a position to believe much in fairy-tale endings these days," he says. "Love has always disappointed me. But the discovery of art has always given me a happy ending."

The Pet Shop Boys' art is his current focus; they are, he says, "really great musicians" eminently capable of writing for ballet. "People say, 'are you excited doing a project with pop music?' but when [the great choreographer Marius] Petipa worked with Tchaikovsky, I guess Tchaikovsky was the pop music of the time."

De Frutos doesn't blush to mention himself alongside the greats – but he's equally eloquent about his failings and frustrations. Dance is a profession he "doesn't like much", he says flatly. He is still plagued by insecurities. "Every time I start a new job," he complains, "it's like relearning how to ride the bike. And I'm always terrified of falling off the bike." That fear is compounded by the fact that "my career is the only thing that's real. My professional success hasn't translated into making me happy in my personal life. When I spend almost 20 hours a day working on this, I don't get a life outside of it. But then, when a job ends, I jump into another one immediately. Because when it's over you feel the grief and the void of it."

Yikes. This would be depressing if De Frutos didn't pronounce it all with such theatrical panache. He admits that his feelings about dance are "very Black Swan" – not least when "I catch a glimpse of myself in the rehearsal room mirror and think: who the hell is that? I feel like my dancers, but I don't look like them any more. It's terrifying. What I hate about the profession is how much we depend on our bodies." (There's also the worry that, as De Frutos says, "after 45, a gay man is dead".)

His professed alienation from dance was accelerated by the Eternal Damnation hullabaloo – by which De Frutos claims to have been deeply hurt. He can picture that booing audience still, in slow motion, "screaming and shouting obscenities at my dancers and the orchestra," he recalls. "Ballet hooliganism. Please – what the fuck is that? It was horrific."

Others argue that De Frutos knew exactly what he was doing. He'd been commissioned to create a piece "in the spirit of Diaghilev", the great Russian ballet impresario and scandal monger. And so his nugget of papal-pornographic baroque was (in one critic's words) "calculated to a tee to provoke walkouts and boos".

Perhaps. But I doubt he anticipated the BBC pulling its planned broadcast, or indeed the death threats, which "affected my health greatly", he says. "I got scared of anything and everybody." Nor – he claims – did he foresee the accusation, by this paper's dance critic, Jenny Gilbert, that Eternal Damnation "unleashed personal spite" in the form of a veiled attack on his ex-employers at Phoenix Dance Company – from whom he had recently and acrimoniously split. That, says De Frutos, is "absolute bollocks". So there's no truth in the claim? "None. The show was about Diaghilev. I'm not going to parade all that personal stuff when I'm paying homage to the greatest impresario in dance history."

Such is the rage with which, 18 months on, he discusses the furore, it's hard not to finger that episode as the "most incredible thing" De Frutos has experienced. And he can't guarantee that his new "family ballet" will be any milder-mannered than the shock-and-schlock offerings that have preceded it.

"What is our obligation in making work?", he asks. "You must always pose questions, and try to answer some – and the exchange with the audience must always be utterly interesting." He pauses, lets the anger subside into mischief. "Somebody said that the best gumbo is the one where the chef spits in the pot. You don't want to know it's happened – but the gumbo is divine."

Sadler's Wells (0844 412 4300) Thur to 26 Mar

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies