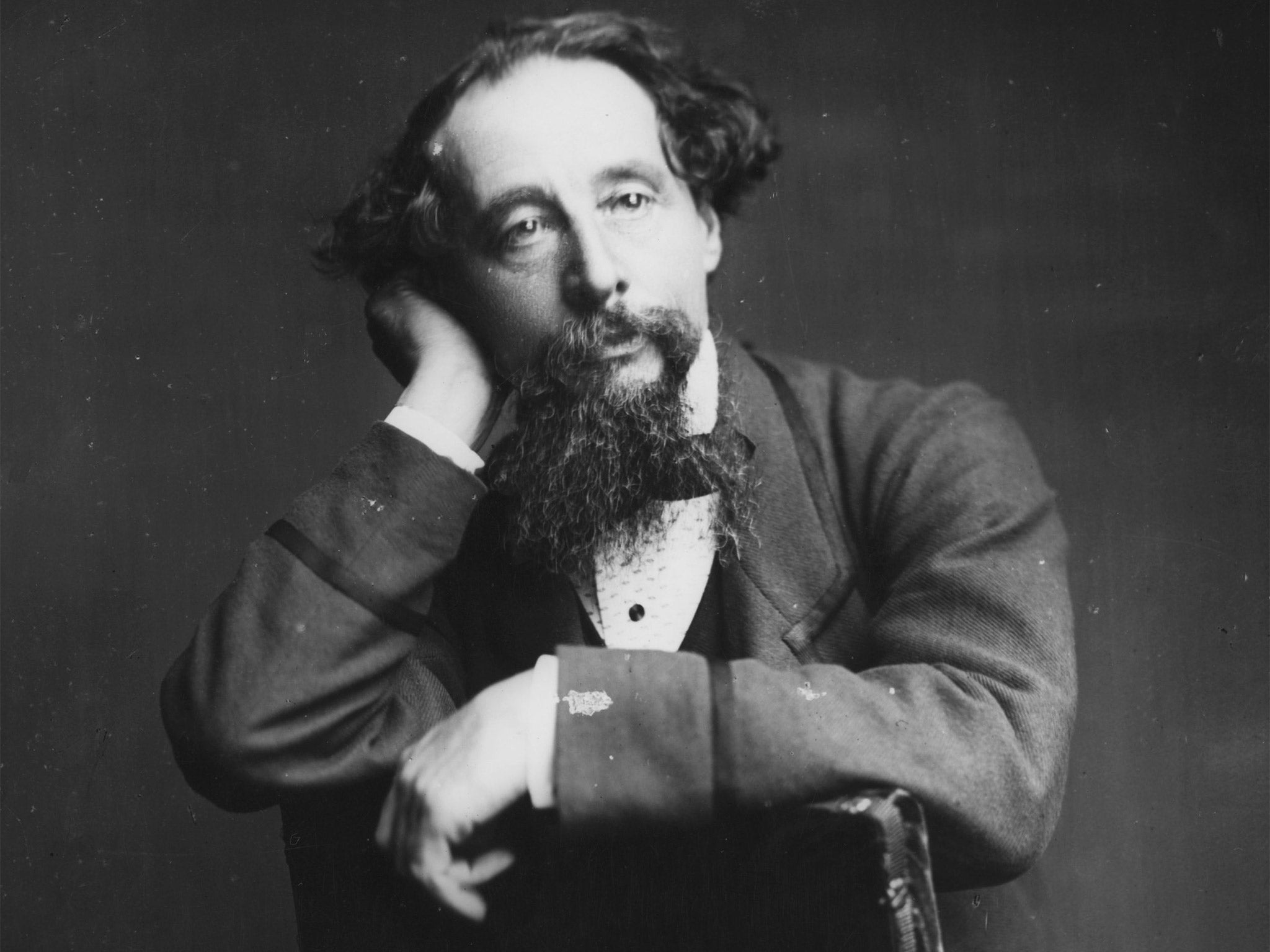

Tony Jordan: 'I turned down the chance to research Charles Dickens for a TV series nine times ... then I found a kindred spirit'

The man behind 'EastEnders' and 'Life on Mars was convinced that, as writers, he and Dickens had absolutely nothing in common. How very wrong he was...

It was rather a curious experience as the hairs on the back of my neck all at once stood upright, as though a call to arms had been shouted from somewhere in the room. This was accompanied by a shiver that I felt so intensely, it was as though a ghost had passed through me, which it had. I had just entered the study of Charles Dickens.

As a television writer, I felt a little like a Sunday League footballer pulling on Pele's boots just to see how they felt; to see if that's where the magic resided. I was staring out of the same bay window of Gads Hill Place in Higham, Kent, that Dickens had stared through as he wrote about a terrified Pip being grasped by the convict Magwitch as he tended his parents' grave.

I had always thought of Dickens and me as being at opposite ends of the literary scale; he made his name with The Pickwick Papers, while I cut my teeth on EastEnders. He went on to write Great Expectations and A Tale of Two Cities and I wrote BBC dramas Hustle and Life On Mars.

Of course, like everyone else I had often heard the assertion that if Dickens were alive today, he'd be writing soaps, a notion I very much suspect was first mooted by my fellow soap writers as part of a cunning plan to elevate our literary status. Some bright spark at the BBC had clearly heard this assertion and so thought I would be the perfect person to "get under the skin" of Great Expectations, what is arguably Charles Dickens' greatest novel, for a new documentary series The Secret Life of Books. The brief was to try to understand the creative process from a "fellow writer's perspective", which I thought not unlike interviewing an ass about the difficulties of running in the Derby.

I turned them down nine times, muttering words like "ridiculous" and suggesting Simon Callow instead but, in the end, either because of their dogged persistence or because my own curiosity about the real Dickens had been tweaked, I agreed.

To give some context, although a writer, I had little formal education. My schooling ending abruptly at the age of 14, as the education system unilaterally decided to terminate our rather tempestuous relationship. My love for Dickens came not from a degree in English Literature or a detailed analysis of his writing steered by scholars of his work, but as a punter, from simply marvelling at the characters and the narrative on the page.

So I was completely convinced that, as writers, Charles Dickens and I had absolutely nothing in common. How very wrong I was.

I have spent a good deal of my working life fighting deadlines, raising finance for my projects, watching my work going out on TV, then analysing the ratings with my heart in my mouth. During my initial research, I was fascinated to learn that Great Expectations was first published not as a novel, but as a serialisation in a periodical magazine owned by Dickens himself called All The Year Round. Not only that, but I also learned that he rushed out this new story because the periodical was haemorrhaging readers and Dickens knew that the best way to turn things around was a new work from him.

Intrigued, I found that original publication and read the first instalment of Great Expectations as it had first appeared in the public domain in December 1860. If this much-loved novel was written episodically as a great deal of my own work had been, then perhaps I could really begin to understand Dickens as a writer, knowing that, just as I did, he would have needed dramatic hooks to keep his audience coming back. These end-of-episode hooks had been my stock in trade when I was working on EastEnders. "You ain't my Mother – yes I am!" followed by what became affectionately knows as the "duff duffs", the iconic drum beat which signals the end of an episode.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/mo. after free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

I admit to having skimmed straight to the end of the first instalment of Great Expectations and there it was: a cliffhanger! The first part ends as the young boy, Pip, steps out alone from the warmth and security of his home, to go back out into the marshes to deliver the file to Magwitch. I could almost hear the duff duffs.

I flicked quickly through to the following week and the second instalment, passing through the text as quickly as I could to the end and there it was again. The second cliffhanger was even more brazen – having secretly delivered the file to Magwitch, Pip was worrying about his mission being discovered, when... a party of soldiers carrying muskets turned up at his door!

At the beginning of the third instalment, Dickens then shamelessly has the soldiers announce that they were there not to arrest Pip, but to have Joe the blacksmith repair their faulty handcuffs. Genius.

So Charles Dickens was now a writer who rushed through a story to save his own periodical magazine from potential ruin, then kept his audience coming back week after week with well-plotted but blatant cliffhangers until they were hooked. In my day, we referred to the secret of soap writing being the deferment of gratification and, to me, the perfect episode of EastEnders would make you laugh, make you cry and leave you desperate to see the next episode. So I was astonished as I looked further into this element of Dickens' work to discover that his close friend and fellow writer Wilkie Collins described this approach as "make them laugh, make them cry... make them wait".

Perhaps Charles Dickens was more of a kindred spirit than I'd dared hope.

But I discovered something else. Dickens' original ending was rather downbeat; after all their various trials and tribulations, Pip randomly bumps into the love of his life, Estella, and they exchange a few pleasantries before they go their separate ways. According to Dickens himself, he showed this ending to his friend and fellow author Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who was horrified, telling Dickens that his audience would be furious; to put Pip through all that he had; for him to have learnt the lessons he did; to make the moral choices made, but then not to reward him would cause riots among his readership. He must, at all costs, give them a happy ending.

Everything I had believed about Charles Dickens to this point would have suggested that he would tell his friend Bulwer-Lytton to go to hell; that a writer of his stature was beyond such a thing; that the story and its ending had an integrity to them. Yet Dickens did change the ending. In fact, he changed it twice until he settled on Pip and Estella standing in the ruins of Satis House – Miss Havisham's lair – and the words: "I took her hand in mine, and we went out of the ruined place; and, as the morning mists had risen long ago when I first left the forge, so the evening mists were rising now, and in all the broad expanse of tranquil light they showed to me, I saw no shadow of another parting from her."

There is still a sense of ambiguity; no wedding bells or happily ever after, but it at least allows the reader to imagine a happy ending, should they desire to do so. Once again, I could see Dickens as a writer constantly aware of his audience; aware of the commercial consequences to the creative decisions that he made.

None of which diminishes his extraordinary talent, nor does it detract from his standing as the greatest novelist that we have ever produced. It simply makes him human; a man with a creative process rooted in the real world.

The final part to my puzzle was looking beyond his talent as a writer, to learn about Dickens the man. I could see how his troubled childhood had inspired and influenced his work.

Born in Portsmouth in 1812, the second of eight children, Dickens' family constantly struggled for money and relocated first to London and then to Chatham, Kent. At the age of 12, his father John, a clerk at the local dockyard, was arrested and sent to jail for failure to pay a debt. Charles had to leave school and was sent to work in a shoe polish factory where he met a man called Bob Fagin, a name he would later use in Oliver Twist.

As I stood in the Kent marshes just as Dickens had as a child and watched container ships move silently along the Medway in the distance, I could feel the young boy beside me, staring not at container ships, but huge prison "hulks", crammed with convicts. Later in his life, that young boy would go on to create a convict who had escaped from one of these hulks who would be known to millions of readers.

The house that Dickens bought in Gads Hill was the house that he and his father used to walk past when he was a child, the house that his father suggested that the young Charles Dickens should one day buy if he were ever "successful enough".

In later life, Dickens may have left his troubled childhood behind, but he replaced it with an equally troubled adult life. His 10 children in a mostly loveless marriage with his wife Catherine further complicated by his well-publicised affair with Ellen Ternan.

As a writer, my life experiences are the well from which I draw my characters and their narratives; my working-class background in the north of England, the loss of my mother as a teenager, my infidelities, my rather earthy years as a market trader, my divorces and my six children all provide me with the core material for the things I write about. Before making this film, I had viewed Charles Dickens not as a fellow writer, but as someone apart from me, a literary deity to be worshipped.

But as I sit here in my writing shed, I feel a shared experience, a genuine understanding of his creative process, a real empathy for a man with an extraordinary talent, but who was not precious, a man well aware of the commercial possibilities of his work and how to exploit them. So with the new, but very real feeling of Charles Dickens as a fellow writer, as an unlikely but kindred spirit, I am now about to undertake something extraordinary.

I am making him my writing partner.

I am about to make a new drama series for BBC1 called Dickensian. It will be a world inhabited by all of Charles Dickens' wonderful characters; a world where Fagin from Oliver Twist can talk to Ebenezer Scrooge from A Christmas Carol; where Little Nell from The Old Curiosity Shop shares a bun with Clara Peggotty from David Copperfield; and Honoria Barbary from Bleak House is best friends with the young Miss Havisham from Great Expectations. A world in which Scrooge & Marley's counting house is in the same street as The Old Curiosity Shop, Venus the taxidermist, The Three Cripples Pub, Fagin's lair and the offices of Tulkinghorn & Jaggers. A world in which we will discover how Jacob Marley died and what happened to Miss Havisham on her wedding day... and yes, we'll have a few cliffhangers.

'The Secret Life of Books' starts on BBC4 on 2 September. 'Dickensian' will be on BBC1 in 2015

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies