Bitcoin’s growing carbon footprint could crush its potential

Bitcoin is increasingly at odds with sustainability. As it grows, coordinated policy response will become more important – but this could destabilise the entire cryptocurrency

The global cryptocurrency market has been riding high of late and topped $2 trillion (£1.4 trillion) in April 2021 for the first time. But one of its best known advocates, tech entrepreneur Elon Musk, pulled the brakes on its rise when he announced this week that Tesla would be suspending customers’ use of Bitcoin to purchase its electric vehicles. The decision (made via Twitter) wiped an estimated $365 billion (£259 billion) off the market.

Cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin are digital or virtual currencies – using decentralised networks based on blockchain technology – are currently receiving renewed attention as a possible counter to the risk of post-pandemic inflation. At the same time, the debate has resurfaced about its fast-growing energy consumption, carbon emissions, and environmental impact.

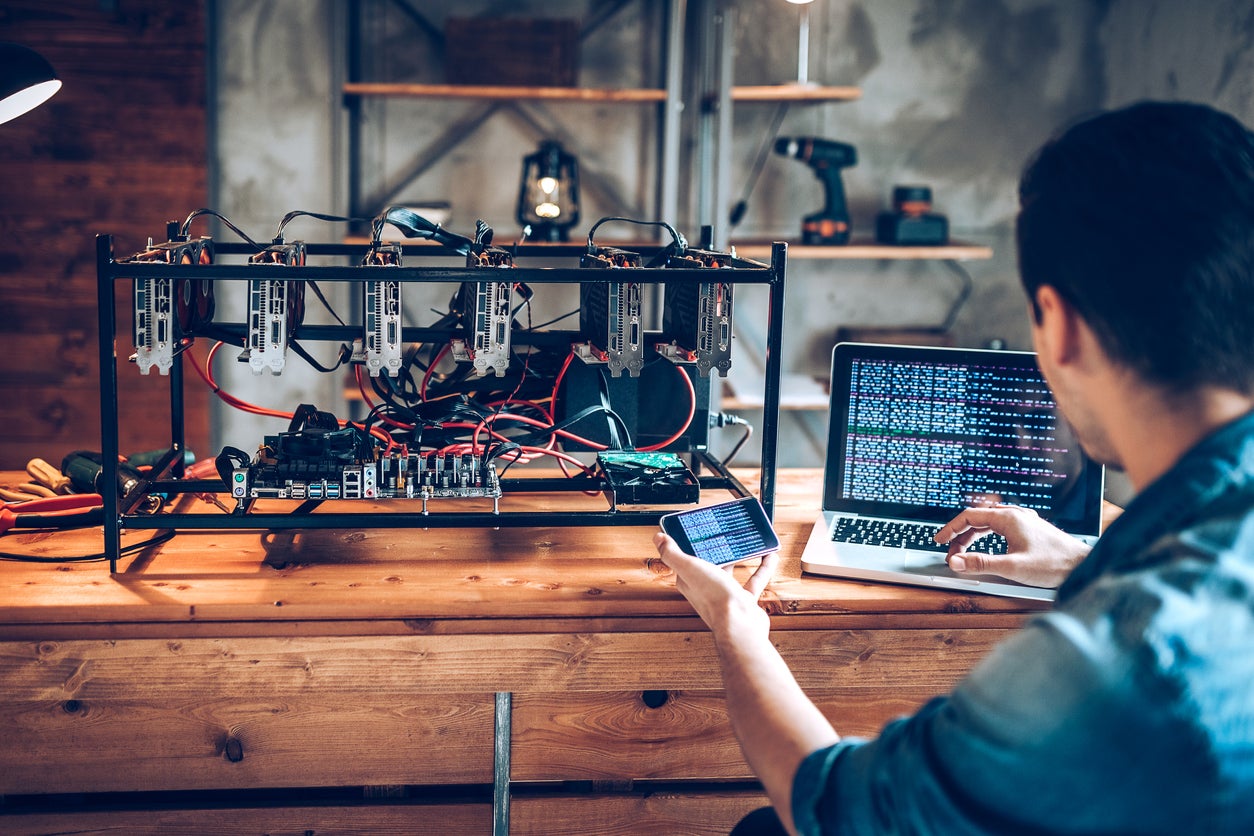

While Bitcoin’s advocates have long downplayed the growing carbon footprint, it has become harder to ignore. The “proof-of-work” mining – computers solving complicated mathematical problems – created to make transactions secure is an essential process requiring large amounts of energy, creating a fast-growing emissions impact already rivalling that of small countries. By design, the computation effort required for mining becomes larger as computers get faster and more people compete for the rewards of the mining. This creates an expectation Bitcoin’s energy consumption will continue to increase especially if Bitcoin transaction fees and hashrates (their total combined computational power) continue to increase as predicted.

In addition to its growing demand for energy and processing power, Bitcoin mining requires special hardware rigs. These rigs contain specialised processors with material and metal requirements. When they come to the end of their lives they create a mountain of waste, electronic waste has become the world’s fastest-growing waste stream.

Most Bitcoin mining is taking place in China, home to four of the five largest Bitcoin mining pools – including F2Pool/DiscusFish, Poolin, Huobi Pool, and AntPool. Mining pools control around 75 per cent of the Bitcoin network’s collective hashrate.

Being located in China enables the pools to take advantage of extremely cheap electricity prices, and Bitcoin miners tend to operate in areas where excess electricity is available, such as the wind power base in Xinjiang or cheap coal-fired power, obviously bad for Bitcoin’s carbon footprint.

Policymakers and legislators are becoming more aware of this problem. The New York State Senate has sought to halt Bitcoin mining for three years until its climate impact is assessed. But as Bitcoin deliberately has no central governance, any local bans on mining will simply push the work elsewhere.

There have been arguments, including until very recently from people like Jack Dorsey and Elon Musk, that Bitcoin can use surplus energy from renewables and thereby incentivise renewable energy development and distribution, but this thinking is flawed. There is actually a lot of demand for this otherwise unused energy, for the generation of green hydrogen or recharging of the growing electric vehicle fleets, and smarter grids make it easier to avoid allowing any generated energy going to waste.

There is also an inherent risk to Bitcoin itself. With so much mining power centralised in a single jurisdiction, this exposes the global network and its users to a large degree of political risk – which is ironic as Bitcoin was designed explicitly as a decentralised digital currency with no one group or jurisdiction in control.

The Chinese Central Bank identified Bitcoin as a financial risk and started putting pressure on local governments to encourage Bitcoin miners to quit. Furthermore, in October 2020 the People’s Bank of China published a bill to pave the way for the digital yuan while at the same time putting in place a ban on crypto issuance and trading for other coins.

New climate targets from China’s 14th Five Year Plan aim to create stronger controls over coal-fired power and high energy-consuming industries, which could impact Bitcoin’s mining through carbon taxes or site regulations to such a large extent that it would likely destabilise the entire global Bitcoin network.

Bitcoin is increasingly at odds with the pressure to deliver sustainable, green economies. Not only will this give governments reasons to shut down Bitcoin mining but ethical consumers and investors are likely to shy away from using or investing in such a wasteful technology and it was arguably such pressure that led Elon Musk’s Tesla to step back from accepting Bitcoin.

Other cryptocurrencies such as Ether, which uses Ethereum as its blockchain, are explicitly planning to move away from proof-of-work to alternative validation approaches such as proof-of-stake, while any new cryptocurrencies are likely to emerge with climate concerns and efficiency at scale built into them from the start.

Although it goes against the rather anarchist origins of cryptocurrencies, institutions such as Wall Street are beginning to explore central bank digital currencies, and these could be more consumer-friendly and safer investments because of explicit government backing.

There is no doubt that cryptocurrencies and blockchains in one form or another are here to stay, even if Bitcoin and proof-of-work are not sustainable. But International cooperation around digital currencies and a coordinated policy response will become increasingly important, challenging the notion that digital currencies should be free from explicit governance and government regulation.

Dr Oli Sharpe is an independent researcher in artificial intelligence, University of Sussex, and a host on the YouTube channel Go Meta

Patrick Schröder is a senior research fellow on the Energy, Environment and Resources programme at Chatham House

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies