The Big Question: Has the bottom dropped out of the contemporary art market?

Why are we asking this now?

Because the art market is showing sure signs of faltering after six years of boom.

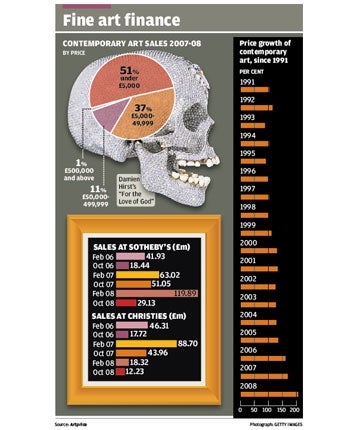

Sotheby's auction house suffered a near 40 per cent slump in its share price last month in the wake of disappointing sales of impressionist and modern art, prompting speculation that the bubble has burst. One Sotheby's sale failed to reach its low estimate of $339m, securing only $223m. Twenty-five of the 70 lots remained unsold, including paintings by Monet, Matisse and Cezanne. Museum-quality paintings by Mark Rothko and Edouard Manet also failed to sell at a Christie's auction in the same month. Major sales by Sotheby's and Christie's in New York achieved totals that were millions of dollars below even their lowest estimated prices. The Christie's president, Marc Porter, reportedly blamed the "difficult economic climate" for the poor results. Panic among dealers reached fever pitch when not even Damien Hirst's Midas touch could not prevent his painting of four skulls, tipped to fetch $3m in New York, from failing to attract a buyer.

Is the art market crashing?

The Art Newspaper reported that auction houses were reducing guarantees and lowering reserve prices in the aftermath of weak sales to fend off an outright crash in the market. Ian Peck, the chief executive of the financing company, Art Capital Group, said the concept of a recession in the art market was no longer an abstract but real condition. He predicted that prices could come down by 20 to 40 per cent. The Wall Street analyst, George Sutton, meanwhile, has predicted entry into "what could be a challenging year for the auction market". But auction houses have been defiant against any doom-laden talk of the bottom falling out of the market – Sotheby's suggested that pre-sale estimate prices for works merely needed re-adjustment for the new economic climate. A statement after a disappointing sale last month said: "[The] sale was assembled over the summer and, by the time the catalogue came out, we were living in a completely different world."

Will contemporary art be immune to crashing prices?

No, quite the opposite, according to the experts. Traditional sectors of the market such as Victorian paintings, Old Masters and prints tend to stay steady and even flourish in times of economic uncertainty. It is the contemporary and urban art market that has born the brunt of economic decline this time round. Ivan Macquisten, editor of the trade bible, Antiques Trade Gazette, said: "Certain elements of the art market are not doing too badly but others have bombed. People were climbing over each other to get to urban and contemporary art sales in the summer, but in October they weren't anymore.

"More traditional art sectors, such as Victorian paintings, were not part of the boom so are not part of the bust.

"The contemporary market has, no doubt, crashed but this is partly because prices were so high that it had the greatest distance to fall."

The contemporary art market has tended to be the most vulnerable due to the relatively flighty buyers attracted to it for a fast financial investment, such as City bankers wanting to make a "quick buck", who have been hit worst in the recession. The moment the art market gets jittery, these buyers tend to disappear.

Can the Turner Prize, announced last night, help the art world?

The prize undoubtedly carries the greatest kudos in the art world but it has served to grant artists international recognition rather than financial rewards. The key to commercial art works is its collectability, not its artistic integrity, according to Mr Macquisten. He said: "I would be very surprised if the Turner Prize had any effect whatsoever on prices. It can establish a reputation of an artist such as Grayson Perry or Martin Creed and can bring them more collectors, but it doesn't always happen."

Is the art market more resilient than others?

Last year, astonishing sales fuelled hopes that the market might be credit-crunch proof, but this is increasingly proving not to be the case. Experts believe the market can lag up to 18 months behind the economy. Warnings that the unprecedented boom in art could soon come to an end in the light of growing financial instability were being sounded more than a year ago, namely from Charles Dupplin, chairman of the art division at Hiscox, Europe's largest insurer of fine art. In November 2007, he said: "There could be an art market correction. On the whole, there must at least be a flattening off." But Mr Macquisten said the art world had proved itself to have great resilience in the past. "There is evidence that it has more resilience than other markets in the long term. There are certain indices which show that if you have invested £100, the returns have tended to be better in the art market compared to the stock market."

Is any contemporary artist bucking the trend?

While Damien Hirst has pledged to re-price his work, his daring auction at Sotheby's in September earned an astonishing $188m over two days in September, coinciding with the collapse of the investment bank Lehman Brothers. But the 43-year-old artist, who has a personal fortune estimated at £200m, suggested last month that even he would be adjusting his prices to take the recession into account. He hinted that contemporary artworks, including his own, were over-priced in recent years and that he might sell for less: "I think [an adjustment in art market prices] is quite good because it became unreal," he said. "Four years ago, you could buy something for £50,000. If we went back to that it's not such a problem. What goes up must come down. It's like when John Lennon went to get his long hair cut and someone asked him, 'Why are you cutting it?' He said, 'What else can you do after you have grown it long?'."

Is there a silver lining?

For those who still have liquidity, buying art and storing it until prices rise again has proved to be a wise way to make money. Rather like in property, those who can afford it tend to sweep up bargain buys in auction houses whose prices have been reduced, then sell them on in two to three years. This means the art market avoids stagnation and some of the best deals can be cut at auctions now.

Will the wealthy prevent the market crashing?

Experts have suggested that if super-wealthy collectors from Russia, China, India and the Middle East keep buying with confidence, the market can weather the economic downturn. In May, it was revealed that Roman Abramovich, the billionaire owner of Chelsea Football Club, was the buyer of an $86.2m triptych by Francis Bacon. Days earlier, he paid $33.6m for Benefits Supervisor Sleeping by Bacon's old friend Lucian Freud.

Is the dip limited to Britain?

No. Prices for modern and contemporary works have dropped by between one third and one half at sale rooms around the world. This has cost the three big houses – Sotheby's, Christie's and Phillips De Pury – millions of dollars.

Has the time come to invest in some artistic bargains?

Yes...

*The art market has out-performed the stock market in the past decade.

*Art is a great investment because it gives pleasure every time you look at it. The same cannot be said for share certificates or savings plans.

*Prices are low right now and even if you don't like the art, it can be sold in a few years' time for profit.

No...

*The market may well deteriorate further, so now might not be the right time to buy.

*Insurance premiums for pieces of art can be high – so even if your investment does well there are other costs to consider.

*When purchasing art it helps to be expert – it's too easy to be caught out.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies