This Kodak moment may be an extremely sad one

With the photographic giant facing bankruptcy, David Usborne assesses its place in society

When companies go bust, we – the customers – rarely pay much heed. It's all about judges, restructuring and then, if they are lucky, their re-emergence in some shrunken form. Not so in the case of Kodak, which is now taking the walk of ignominy to the bankruptcy courts. This is a company we care about.

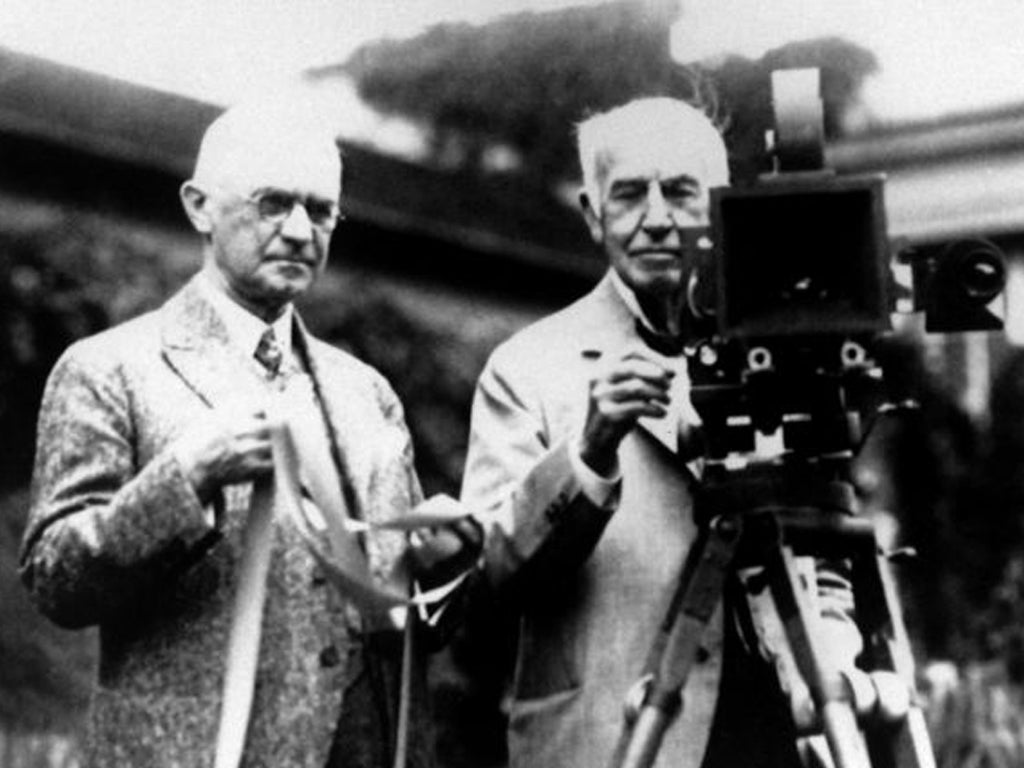

That is to say – and herein the nub of this tale – we care about Kodak if we were born before 1986 or so. That year marked the 100th anniversary of the invention by the company's founder, George Eastman, of roll film that replaced photographic plates and allowed photography to become a hobby of the masses. And it was when it was near or at the peak of its commercial powers. Based in Rochester, New York, Kodak may not have owned the 20th Century, but it did become the curator of its memories.

"One of the interesting parts of this bankruptcy story is everyone's saddened by it," notes Robert Burley, professor of photography at Ryerson University in Toronto. "There's a kind of emotional connection to Kodak for many people. You could find that name inside every American household and, in the last five years, it's disappeared."

But 1986 was arguably also the year when Kodak began to be eaten by others, notably from Japan, which learned to innovate too and more quickly. This Chapter 11 story is painful and not just for its current and ex-employees relying on its pension plans in Britain as well as in America, but also because it is layered with so much irony.

Kodak was the great inventor. In 1900, it unveiled the box Brownie camera. "You push the button, we do the rest," ran the advertising campaign. Kodachrome film, the standard of movie-makers, as well as generations of still photographers because of its incredible definition and longevity, was introduced in 1936 and only went out of production 2009. Nor we should forget the Instamatic, the camera with the little cartridges of film that spared us the fumbling of trying to get film to spool properly.

The trouble at Kodak, analysts will tell you, began 20 years ago, when the writing began to appear on the wall for film photography. True, over the span of the 1990s, the bosses in Rochester poured $4bn into developing the technology for picture-taking capabilities inside mobile phones and other digital devices, but they held back from developing digital cameras for the mass market. Others, like Canon, rushed in. So who first invented the digital camera? Here is the cruelest irony. Kodak did or at least a company engineer called Steve Sasson working with a small team in a laboratory in Rochester. After the kind of tinkering that made pioneers like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates into Leviathans of the computer age, Mr Sasson put together a toaster-sized contraption that, for the first time, could save images using electronic circuits.

It was an astonishing achievement. And it happened in 1975, long before the internet or broadband width had ever been dreamed of.

Partly for that reason, Mr Sasson and his colleagues were met by blank faces when they unveiled their new machine to the Kodak brass. Even he didn't full see its potential.

"It is funny now to look back on this project and realise that we were not really thinking of this as the world's first digital camera," Mr Sasson was later to write on a company blog. Moreover, somewhere in the synapses of the Kodak – which shares the letter 'K' with another icon of American household consumption, Kelloggs – leadership the thought took shape that going digital meant killing film; smashing the company's golden egg.

But there are other things in the history of Kodak that combined to humble it. Even before film began to fade, other manufacturers – notably Fuji – began successfully to nibble at the company's dominance. In recent years, it has also been pulled down by the weight of its pension responsibilities born of a paternalistic culture first introduced by Mr Eastman himself.

Its efforts in the last 10 years to shift focus to consumer and industrial printers have also suffered from missteps. The company has posted losses in six years out of the last seven.

It's remarkable to remember that in 1976, Kodak sold 90 per cent of the photographic film in the US, along with 85 per cent of the cameras and that even 10 years after that, it still employed 145,000 people worldwide, compared to a global payroll today of 18,000. And historians may one day conclude that most of that slow unravelling can be traced back to the invention of Mr Sasson and its success in engendering not excitement in the firm, but fear.

Don Strickland, a former vice president, who left the company in 1993 because even then he couldn't persuade it to manufacture and market a digital camera, put it this way: "We developed the world's first consumer digital camera, but we could not get approval to launch or sell it because of fear of the effects on the film market... a huge opportunity missed."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies