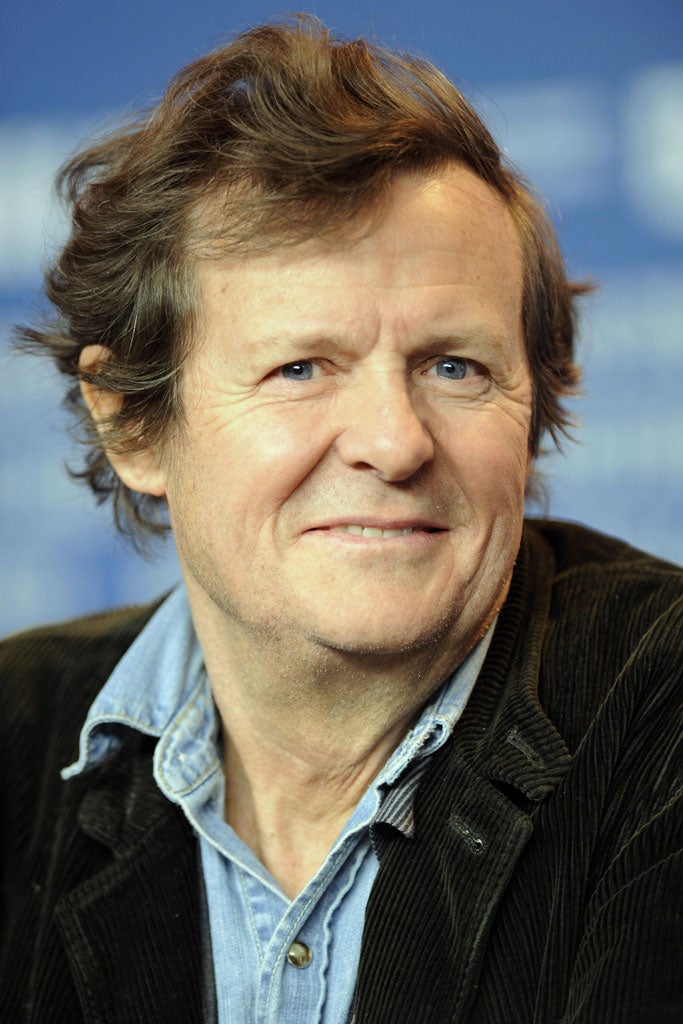

Rebel with a cause looks back in anger

Left-leaning David Hare's new play is based on his days as a scholarship boy at public school. Michael Coveney meets him

If, 30 years ago, you had said that Sir David Hare, scourge of the establishment and intellectual leftie given to cracking scornful jokes, would one day open a new public school play in the West End on a double-bill with a dusty old classic, The Browning Version, by Terence Rattigan – and, what is more, in a theatre renamed for the resolutely non-knighted Harold Pinter – you might have been told to go away, or whistle, or have your head examined.

But that is what is happening this week, as Hare's play, South Downs, based on his experience of being a scholarship boy at Lancing College, comes trailing unanimously good reviews – that, in itself, is almost a first (well, a second: everyone loved his play about the Anglican church, Racing Demon) as far as Hare is concerned – from last year's summer festival in Chichester.

Hare was the leading light of the fringe in the 1970s, more or less the resident dramatist at the National Theatre in the 1980s, the screenwriter of thoughtful, high-quality art-house movies, and now... Chichester, Rattigan, what's going on? Popping in to his study in Hampstead, north London, last week, I can hardly wait to hear his excuses. Typically, of course, he has a clever answer ready.

"TS Eliot, the most conservative of cultural critics, said that you can only add to a tradition by changing it. But at some point, you do actually fall into that tradition, don't you? If you're 64, as I am, you're part of it. So you can put a play on with one of Rattigan's and see the connection, whereas once you would have seen only the difference."

Hare's nothing if not smart, and has an almost unparalleled gift in the British theatre of being able to get up people's noses. That quality of disruption runs like a streak of acid through most of his work, which is usually to do with romantic love, political betrayal or our capacity for grief, and I now think that all of this has to do with emotional and spiritual bravery.

Did he need some of that during his schooldays, surely the happiest days of your life? Hare does his characteristic laugh, half-snort, half-bark. "I was deeply unhappy. I'd been sent to Lancing because my father was away at sea – he was a purser in the P&O Line – and I hated it. Although the boy Blakemore's trajectory in the play is mine, I'm also distributed through other characters.

"The events of the play are fictional, but the atmosphere and culture of the play is Lancing in 1962. I had a lot of letters during the Chichester run saying, 'That's exactly how it was'."

But didn't the school chaplain complain about the scene in a religious class where the doctrine of "consubstantiation" – when the bread and wine represents exactly the body and blood of Christ – is explained and then challenged by Blakemore?

"Yes, he wrote to say that he had explained it perfectly clearly and didn't understand why the boys in the scene were confused. I had to explain to him that this was, in fact, a play, and that the person doing the teaching wasn't even the school chaplain. I did research this extremely thoroughly, and the theology is correct."

Does he really believe some chaplains, social workers and most teachers, nurses and even actors, are the blessed of the earth because they have no chance of inheriting it? "Well, yes, of course I do!" He cannot believe I'd doubt this. "Power triumphs, and usually corrupts. There's a revolting bully in South Downs, whom people might recognise as the sort of person who does very well in life, probably going into industry and/or politics.

"If you think life is about power, then you will prosper, won't you? It's like the line in Citizen Kane about there being no trick to making money if that's what you want to do. And it's the same if you end up running ICI and you are blind to what you or I might think of as taking responsibility for all those people's lives."

In Rattigan's play, a buttoned-up classics master is given a gift by a pupil he thought despises him; the "gift" in Hare's piece is given to Blakemore, the cleverest but unhappiest boy in the class, by the mother of one of his friends, an actress, who suggests to him that his anxiety about the bomb might really be part of his own unhappiness at school.

Personal pain lies behind the public gesture, Hare suggests: "Discontent with the world is so tied up in complicated ways with discontent with yourself, and maybe in this play I've been able to put my finger on that."

'South Downs'/'The Browning Version', Harold Pinter Theatre, Panton Street, London SW1 (0844 871 7627) to 21 July

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies