The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Flanders fields: Pedal into the past

A century since the outbreak of the First World War, Emma Thomson gets a fresh perspective on the horrors of the conflict via a bicycle tour of the area’s memorials

“Come and see this,” shouts Carl from his saddle, as he waves me over to a roadside farm selling leeks. He lays his bike on the ground and walks over to a white garage door. I ditch my cycle alongside his, and jog to catch up. He raises the squeaky door and there, clustered all around an ageing blue Ford Fiesta, are dozens and dozens of browning shell casings, empty gun cartridges and hand grenades.

Carl picks up a rust-bitten Lee Enfield rifle from the table, and cradles it in his hands. “Even now, we uncover stuff like this almost every day from our fields,” he says nonchalantly. “Here,” he says, dropping a spherical bullet into the palm of my hand. “That one didn’t hit anyone because it’s not dented, see.”

This impromptu stopover is precisely what I had been hoping for when I signed up for Carl’s guided cycling tour of the Ypres Salient – a Belgian region that witnessed ferocious front-line fighting between German and Allied forces during the First World War.

Visiting the area’s memorials by car or minibus often becomes a race from one site to another, with no sense of where they are in relation to one another. Carl Ooghe – a trim, spectacled Belgian, who has been devouring history books since he was 14 years old – firmly believes that “to understand the war, you need to understand the geography”. So I had taken to two wheels in a bid to experience the Salient at soldier level and pace.

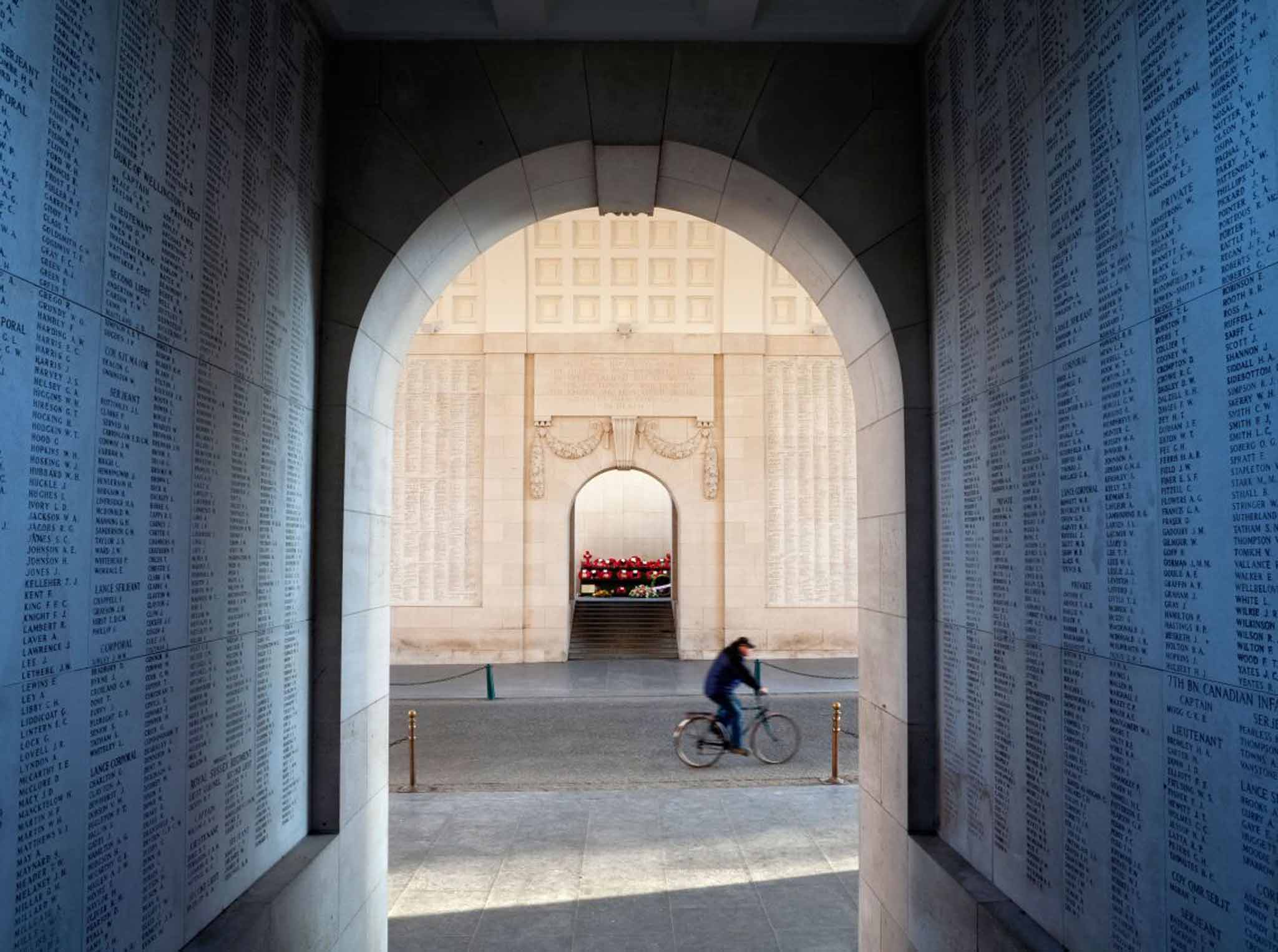

We had started beneath Ypres’ well-known Menin Gate, then jiggled our way across the city-centre cobblestones, until we were out in the countryside and following the muddy Yser canal north towards Essex Farm Cemetery – the site of an advanced dressing station, where the wounded were triaged, just behind the front line. It was here that Canadian surgeon Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae penned the haunting In Flanders Fields poem after witnessing the horrific death of his best friend Alexis Helmer from a shell.

It’s a higgledy-piggledy cemetery with irregular gaps between the graves, and some facing in different directions. “Essex Farm is a battlefield cemetery: it was so close to the front line that the dead were buried when breaks in the shelling allowed for it,” Carl explains. “The soldiers would bang together makeshift wooden crosses from empty ammunition boxes, but when the shelling started again, the crosses were blown from their plots and the soldiers’ exact burial places lost. The headstones are a rough estimation of where the men were thought to be buried.”

The positions of the tombstones reveal other touching details, too: “Do you see those five stones standing shoulder to shoulder, without gaps?” Carl asks, pointing across the cemetery. “That usually means they were a group of friends that had been huddled together gossiping and smoking when they were hit by a shell. Their remains would have been so intertwined that their comrades had to bury them all together.”

We press on, pedalling along an old railway track covered thinly with bitumen, towards the German cemetery of Langemark. The fields round here are filled with maize stubble and drooping stalks of Brussels sprouts. We gently lean our bikes against the outer wall and step through the entrance arch. Created after the war, its tombstones stand in strict lines and stern-looking memorial blocks surround a mass grave in the middle. “Do you notice anything unusual?” Carl enquires, nodding towards the blocks. I scan them for a few seconds, but return a puzzled look. He points, silently, to a name near the bottom of one of the plaques. It glimmers faintly; the brass rubbed clean by respectful hands. “That’s a British name!” I exclaim. “Yes, indeed! In fact, two British soldiers – Privates Carlill and Lockley – are known to have fallen here and the Germans respectfully included their names when the graves were consolidated in the 1950s.” I’d have walked straight past the plaque had I been on my own.

Just then, the whoops and yells of a school group break the quiet, so we return to our bicycles and head south towards Tyne Cot – the world’s largest Commonwealth war grave cemetery. Soon enough, the cemetery appears on our left. From afar, the 12,000-plus headstones look like rows of ivory dominoes, fragile and ready for a fall – like the soldiers’ own lives.

We cut across backroads and puff our way uphill to a site known as Crest Farm, just west of Passchendaele. It sits on the cusp of Passchendaele Ridge – an elevated strip of land that was the focus of bitter fighting between the Germans and Allies because it afforded 180-degree views of the surrounding countryside. Mainstream tours rarely visit the outcrop that overlooks a great swathe of open fields, yet it was the scene of a critical turning point in the Third Battle of Ypres in October 1917 that would eventually win the Allies the war. “Hilltops were the eyes of the artillery: if you controlled them you could easily target the enemy. Machine-gun fire could stretch for 4km (2.5 miles), you know. Field Marshal Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Forces, was desperate to claim Passchendaele before Christmas, so he ordered the troops to march across the ground you see below. They were completely at the mercy of the Germans, who hid in the treeline and mowed them down. Four Australian divisions were annihilated, but a Canadian Corps battled on for three weeks to eventually claim the ridge.”

As Carl describes the fighting that played out here, I can almost hear the barrage of gunfire rattling in the distance; see the faded shadows of soldiers struggling to advance across a quagmire of mud. We both turn and leave in silence.

We do a sharp U-turn and head towards our last stop: Polygon Wood Cemetery and the adjoining Australian Buttes Cemetery created after the war. “Did you know that parents often used the last line, of the last letter, their sons sent them for the epitaph on their grave?” Carl asks as we pace slowly between the headstones. “No, I didn’t,” I reply, absent-mindedly fingering the bullet he had given me earlier as it rolls around my pocket.

He comes to a standstill in front of one, turns to face me and asks: “What would you tell your mother if you knew you were facing certain death?”

“I’d tell her I was all right.”

Without a word, Carl steps to the side to reveal the stone he has been blocking. It belongs to Lieutenant Harold Rowland Hill and there, carved into the base, are the words: “I’m all right, Mother – Cheerio.” He was just 22 years old.

I grip the bullet tightly in my hand. This year may mark the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War, but in that moment it feels like yesterday.

Getting there

Eurostar (08432 186 186; eurostar.com) has up to nine departures daily from London St Pancras to Brussels Midi. When booking, select “Any Belgian Station” as your destination and onward/return travel to Ypres using the local NMBS/SNCB (www.belgianrail.be) rail network is included for an extra £10 return.

Cycling there

Half- or full-day cycling tours around Ypres can be booked through Cycling the Western Front (00 32 4 75 81 06 08; cyclingthewesternfront.co.uk). From €75 per person.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies