Ouija boards are the must-have gift this Christmas, fuelled by a schlock horror film

Simon Usborne explores the appeal - and mysteries - of a century-old parlour game

What better time to talk to dead people for fun than the festival to celebrate the birth of Jesus? Ouija boards are flying themselves off shelves and under trees this Christmas, according to trends data released by Google. The company has recorded a 300 per cent increase in searches for the spirit-bothering devices, fuelled by a terrible movie that was effectively a feature-length ad for a board game, an appearance on The Archers, and the Victorian belief that if the dead could speak, they would use a plank of a wood and the alphabet.

Ouija, released in October in time for Halloween, was, by all accounts, a cliché-ridden turkey about a group of teenage girls who experiment with a board and get scared. It has a disastrous 7 per cent rating on Rotten Tomatoes, the review aggregating site, but became an occult hit, to the delight of its backers. Hasbro, the toy company behind Monopoly, pushed for the revival of the film, which had stalled in development, and partnered with Universal to make it happen. Its Ouija Game, including a glow-in-the-dark version, is – sure enough – the biggest seller online.

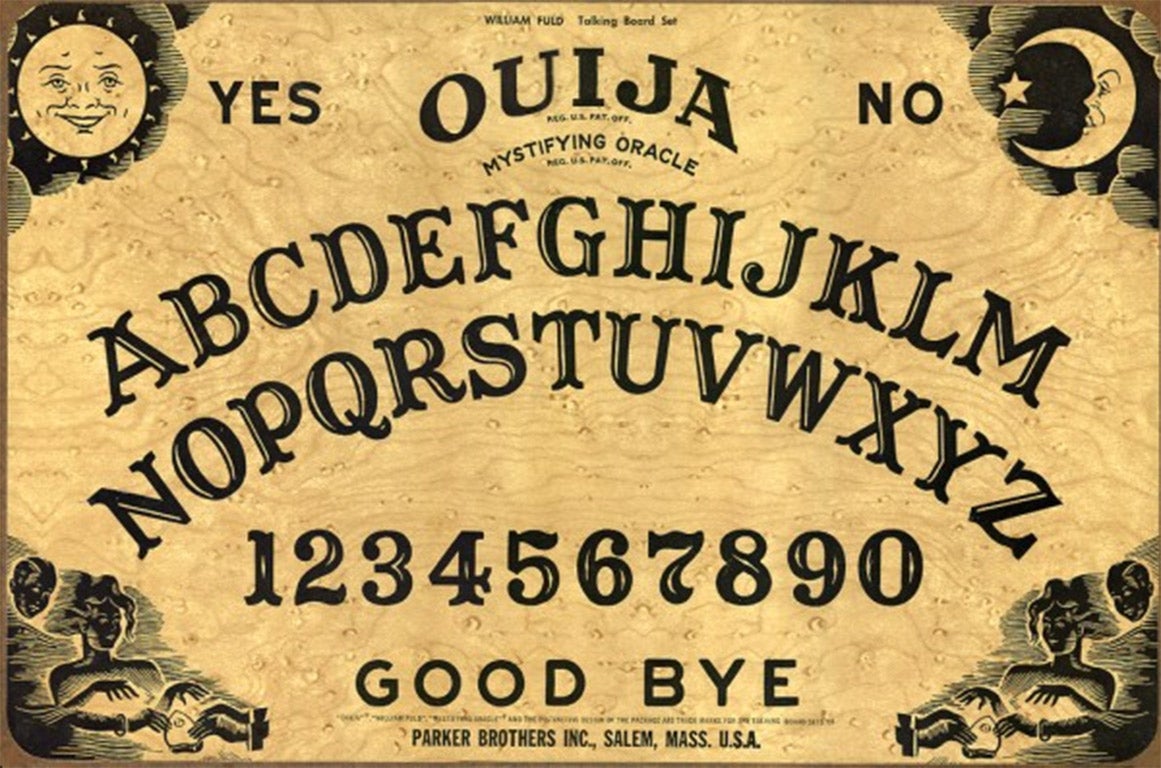

All of which is appropriate, because the Ouija-board trend, circa 1890, was always about selling games. Spirit writing dates back much further. In 12th-century China, it was believed that spirits had the power to guide a "planchette" to write Chinese characters. In the late 19th century, when doubts about God inspired by Darwin's little birds led to a boom in spiritualism, planchettes became a novelty hit in the west. Elijah Bond, an American lawyer and inventor from Baltimore, devised and patented in 1891 "a toy or game by which two or more persons can amuse themselves by asking questions of any kind and having them answered by the device used and operated by the touch of the hand, so that the answers are designated by letters on a board".

Bond's talking board, with its planchette pointer (a small glass is now a popular alternative), was a minor hit in the séances of the time, but it was William Fuld, who had worked with Bond, who made it big. He marketed the board heavily, crushing competitors and copycats. Ouija was a portmanteau of "yes" in French and German, he said (as well as 26 letters, boards include the words "yes" and "no" so that spirits can answer simple questions more quickly). Fuld eventually passed the company to his children who in 1966 sold it to… Hasbro.

If there were any doubt that dead people don't tend to communicate in this way or at all, scientists have been on the case for decades. In the 1850s, Michael Faraday, the electromagnetism guy, devised an experiment to expose a similar spiritual fad. Table tipping required a group of people to rest their hands on a small table, which would then seem to become possessed and move. He created a system of movable cards that would show whether the motion derived from the table or the participants (it was them, of course).

Faraday and other scientists identified the ideomotor effect, which also explains how Ouija boards work (or don't work). Ray Hyman, an American psychologist and early figure in the modern skeptical movement, neatly described it in 1999: "Honest, intelligent people can unconsciously engage in muscular activity that is consistent with their expectations."

In other words, if the questioner at a Ouija board expects a yes or a no, or a word, their brain guides the hand accordingly without their realising it. Other hands in the group follow. Similar experiments show that looking at an object can further compel the brain to guide a hand in its direction. Sure enough, when the letters on a board are only visible to a "spirit", and not the players, their hands produce nonsensical responses.

Yet the creepiness of the exercise and the imagery of films like Ouija can make them fun, especially during teenage sleepovers. In a Halloween episode of The Archers last month, Kenton hosted a séance a The Bull, with far from spooky results. But those falling for the marketing this Christmas should beware the risks of messing with spirits, or at least one's own mind. Two years ago, a 15-year-old boy from Texas told police he had stabbed his friend in the neck because a Ouija board had told him to.

Reports abound online of players freaking out or even committing suicide after sessions. In 1994, a British judge was forced to order a retrial of a man jailed for life for a double murder after it emerged that jurors had used a Ouija board during a drunken night to guide them towards a verdict. A fresh jury found the accused guilty. That time, board games were banned.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies