Lab Notes: The chilling science behind a warming shot

Single malt whisky is one of the finer fruits of fermentation science. At this time of year particularly, there is nothing like the sensory pleasure of feeling the aromatic flavours of a Scotch malt as it rolls around the palate – sending warm tingles down the chilliest of winter spines.

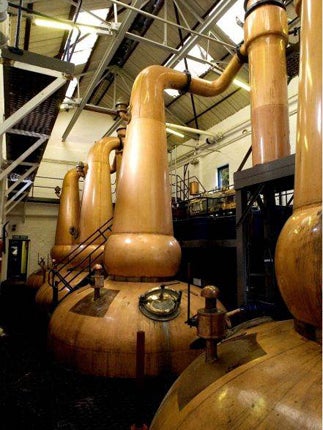

There are many alcoholic drinks made from the chemical waste products of a microbial yeast, but the sheer variety of Scotch whisky flavours is an elegant tribute to the wonders of natural fermentation and the powers of gentle ageing in a wooden cask.

Why then would we ever want to interfere with what nature can offer in terms of taste? This is at the heart of an on-going debate within the finer fringes of whisky-drinking circles over the question of whether single malt whiskies should be "chill filtered" before they are bottled.

Chill filtering is a process introduced relatively recently – primarily in the 1970s – to rid unwanted chemicals in the whisky. These substances, polyphenols such as fatty esters and aldehydes, cause the unfiltered whisky to go cloudy when ice or water are added, or if the whisky bottle is kept at a cold-enough temperature.

The cloudiness does not affect flavour, indeed many would say it enhances it, but it was considered to interfere with the aesthetics of presentation, particularly in countries where ice is routinely added to whisky.

Whisky makers got round the "problem" by cooling the whisky to about 2C prior to bottling and running the liquid slowly through a series of filters to take out the offending cloudy clumps of polyphenols. It was a triumph of marketing over taste because many of these organic chemicals actually imparted their own aroma and flavour.

"What chill filtration really does is make whisky pretty. It makes it more appealing on the shelf," says Ian MacMillan, the master blender of Burn Stewart Distillers, which owns the Tobermory Distillery on the Isle of Mull.

"It's a cosmetic thing, but these compounds have been there since the whisky was distilled and they evolve over the years of maturation, creating aroma and flavour profiles. Why would you want to remove these?" MacMillan asks.

Why indeed. It was for this reason that Burn Stewart Distillers decided to rid chill filtration from its entire range of malts, which includes the briny-tasting Ledaig from the same Tobermory Distillery that produces the smoother malt of the same name, and the 12-year-old Bunnahabhain whisky, made on the island of Islay.

Having tried both the un-chill filtered Tobermory and the Ledaig, I can attest to their superb quality, although I cannot vouch on how much better they are compared to their chill-filtered counterparts, not having comparison "control" samples to hand.

However, MacMillan's judgement is unequivocal. "There is more of a depth, they are more complex and aromatic than when they've gone through the chill filtration process.

"Tasting them side by side you would certainly pick up more intensity on the nose. On the mouth feel, there is also more depth. It has more layers to the whisky and it adds to the length as it stays on the palate. It has a better aromatic feel and flavour," he adds.

There are a few other un-chill filtered malt whiskies, such as Bruichladdich and the 10-year-old Ardbeg – and the Gaelic whisky Te Bheag can apparently be bought in chill filtered and un-chill filtered versions. But no whisky manufacturer, as far as I know, has quite gone as far as Burn Stewart Distillers and abolished the practice from across its entire range of single malts.

It's a bold move in the conservative world of Scotch whisky making. But it's a triumph of taste over the banalities of appearance.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies