Our restaurant reviewer explains why he's become a (part-time) vegetarian

If any of you had the privilege of growing up, as I did, the child of Indian parents in a Western setting, you might have a sharp recollection of the first time you ate meat.

Despite the habits of a growing number of modern Indians, Hindus are essentially herbivores, and so for the first 15 years of my life it was all idli, dhosa, rasam, poori, bhaji, palak paneer and the like – admittedly not a bad deal for a grown-up, let alone a spoilt kid, which is why I ended up as fat as I did.

But when the moment came for the adolescent Englishman in me to assert his dominance over an Indian inheritance, it was through an act of meat-eating defiance. I remember it like it was yesterday.

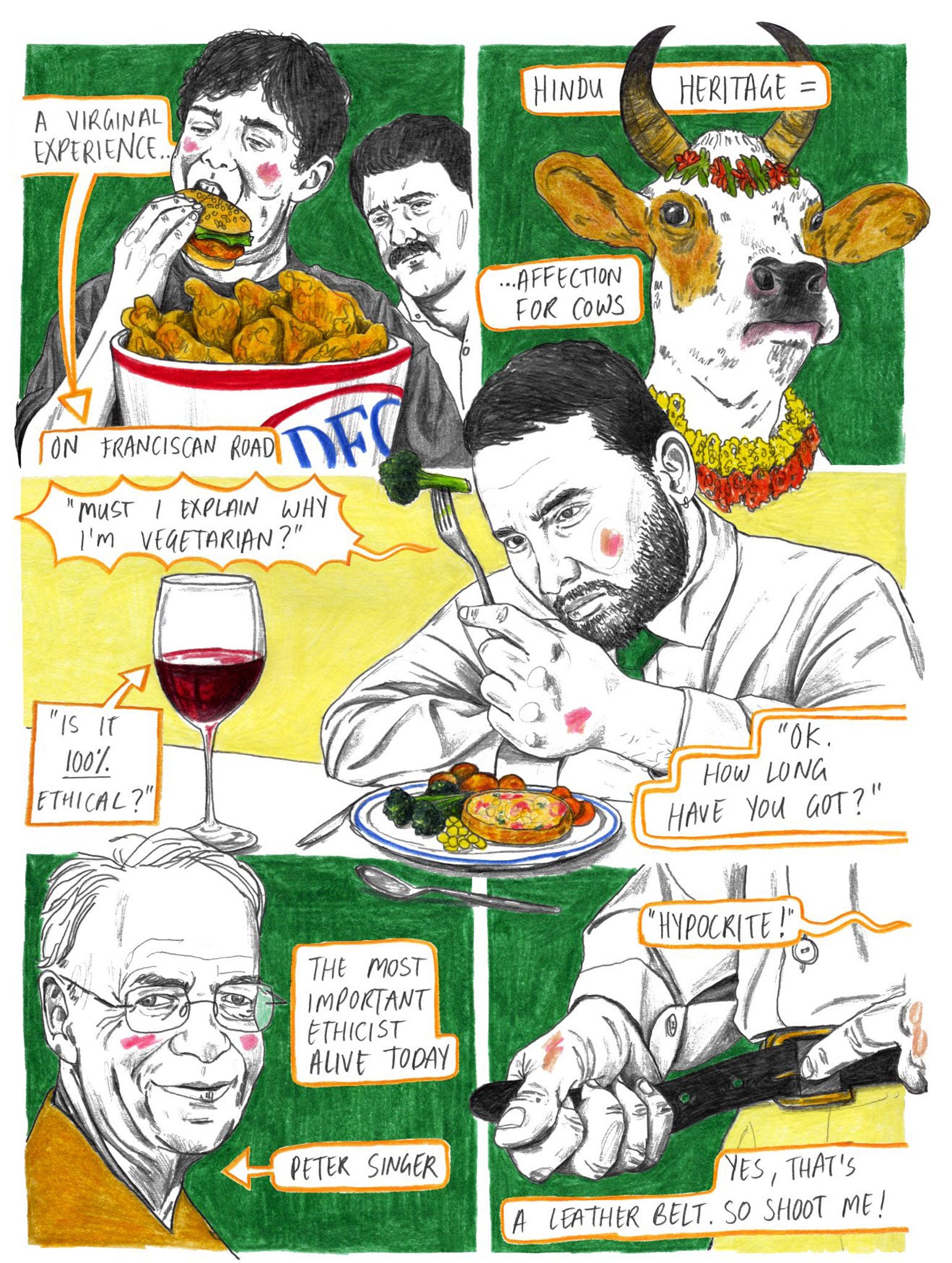

My father, brother and I were within sight of a Dallas Chicken at the bottom of Franciscan Road in Tooting, from whose greasy depths the salted odour of fried poultry wafted out and under our nostrils. We were hungry, having done the Saturday-morning grocery run. My brother, being older and the rebellious type – think James Dean in k a Nehru suit – had already tasted animal flesh, and boasted of its puberty-inducing properties (I was a late developer).

Unwilling to confront, for the umpteenth time, his hormonal eldest, my father ceded to a request for us to quell the pangs in our bellies by heading in. Being vegan, he wouldn't touch the chicken; naturally I would have been happy with just chips.

Imagine my surprise, then, when, unbeknown to me, my brother ordered for the both of us, and I was told that what sat, hot and steaming, in the box before me was a chicken burger. This was a challenge to my nascent manhood; and, not wanting to make myself a candidate for a ribbing from a brother with a belly full of chicken, I indulged.

Three separate aspects of that experience are imprinted on my memory. The first is being horribly aware that my father was staring at me during this virginal experience, a fact confirmed by his question: "How does it taste, Amol?" The second was the answer to that question. Fatty, hot, bread-crumbed chicken with lettuce and mayonnaise for company is one of the finer pleasures yet conjured by our species, and no less appreciated for being delivered to a teenage palate.

The third thing, accentuated sharply by the former two, was a sense that what I was doing was somehow naughty, an act of mischief. To the uninitiated, the act of eating another mammal's flesh is in a fundamental sense an act of transgression, the crossing of an invisible moral rubicon that compromises your capacity, if not to be human, then certainly Hindu. I think it was about three weeks later that I decided I was atheist.

For the following 15 years, I happily ate meat of every kind – the rarer, the better. But something of that sense of transgression sat, marinating in guilt, in the recesses of my imagination. I know this because on a visit to India at the turn of this year I decided to become vegetarian, and it was when confronting a greasy bit of chicken, and thinking about the Franciscan Road challenge half a lifetime earlier, that my tentative re-conversion was secured.

Moral conversions are generally sudden and dramatic. Evangelical types are especially prone to boasting of the following phenomena: visitations from angels, conversations with our Maker, near-death experiences, that sort of thing. My conversion was, I'm afraid, a much more tedious affair. I became vegetarian again because of a nagging sense that it was the right thing to do, and, though a few particular events pushed me over the hurdle, it was the culmination of a process that lasted years. There was no conference with the faithful, or celestial seminar; just the slow and steady erosion of moral resistance.

Like all ethical positions, not eating meat is a matter of both theory and reality, principle and practice. And the two chief characteristics of vegetarianism are that it is right and boring. Of the former, I'm afraid I just can't see what the fuss is about, because as ethical dilemmas go, the case for being vegetarian doesn't qualify. It's not a dilemma.

You see, when scientists at Cern get beyond the Higgs boson, into the tiniest particles of the known solar system, beyond the leptons and muons and neutrinos, they are not – alas for us – going to find particles that are called Good and Bad. In other words, the reasons for doing right and wrong, for being good and bad, are not objective facts, things that exist in time and space like leptons, muons, neutrinos, cows and pigs.

Therefore, to defend acting morally in any particular situation you have to appeal to something beyond the world of facts. Religious types have the comforting delusion of a dictator in the sky, who on days of prayer deigns to provide a code of conduct for his favourite ape.

Those of us in the secular camp know that, given He probably doesn't exist, we need to find a better warrant for doing right and wrong, and being good and bad, than His Will. And here's mine, my irreducible moral metric: suffering is bad. Especially when it is preventable and unnecessary. Suffering occurs when sentient beings – those who are conscious of existing over time – feel prolonged pain.

An awful lot of life on earth obviously qualifies as sentient. But sentience, like temperature, comes by degrees. Some animals are more sentient than others. It is a curious fact that the animals you eat happen to be among the most sentient of all. Higher mammals, such as pigs, cows and lambs, are really very sentient. They have future-directed hopes and are capable of feeling immense pain. To deny either of those assertions is scientifically illiterate.

I hope you're grown up enough to ignore the manufactured tosh about "humane" treatment of animals, and accept what is obviously true, which is that the commercial production of meat for human consumption leads to an unimaginable volume of suffering. It was darkly funny, when the horsemeat scandal hit us, listening to endless Bufton Tufton farmers harp on witlessly about the ethical standards of British manufacturers. Even if it were the case that all these animals led comfortable lives – palpably not true – it would be mere preparation for industrial slaughter. A life of luxury is irrelevant to the fact of murder.

It therefore falls to the carnivores among you to answer these two questions. Do you accept that preventable, unnecessary suffering is bad? If so, why should we discount the suffering of, say, the cow, pig or lamb that ends up on your plate? Or, if you like, why should their membership of another species disqualify them from your sympathy?

In asking these questions, I have been influenced, as have generations of vegetarians, by Peter Singer. The Australian philosopher is the most important ethicist alive today, and though his views on abortion and infanticide have led to his being dubbed a murderer, the argument for vegetarianism he put forward in Animal Liberation (1975) is unanswerable. His utilitarianism, which has been dismissed as cold and calculating, is in fact deeply compassionate; and though I don't subscribe to it completely, all carnivores ought at the very least to engage with that text, on the grounds that you should know your enemy's argument better than your own.

The two other reasons that Singer and most mainstream vegetarian thinking give for not eating meat have great appeal to some but less to me. One is ecological: if you're worried about global warming, stop pretending you're a do-gooder because you eat organic cabbage that's £8 a gram from Whole Foods, and become vegetarian.

In 2007, a study by the National Institute of Livestock and Grassland Science in Japan estimated that 2.2lb of beef is responsible for as much carbon dioxide as an average European car emits every 155 miles, and burns enough energy to light a 100-watt bulb for nearly 20 days. That is why mass vegetarianism has been official UN policy for several years now. In 1961, the world consumed 71 million tonnes of meat. In 2007, it consumed 284 million tonnes. I hate Malthusians who tells us that more people is a bad thing, but if you think of yourself as green, and also eat meat, you're a hypocrite.

The final reason is health. Cutting red meat, in particular, from your diet reduces the chances of getting cancer, and cleanses your colon. You also work harder, I find, to root out vegetables and greens and fibrous things when you can't eat flesh. Vegetarianism isn't always, but often can be, very good for you.

Unless, that is, it turns you into a sanctimonious chump. And I should say in a spirit of honesty that there is an extremely strong case against being vegetarian – namely that a more boring ethical practice could hardly be imagined. For one thing, you have to forgo an astonishing range of delicious food. Vegetarian food can be exquisite – try Mildreds of Soho, or Tamil Nadu if you want to go slightly further afield – but there's no escaping the hole left in your life when BLTs and bourguignon are permanently off the menu.

It's partly for that reason, and partly out of solidarity with the readers of this magnificent newspaper – whom I serve as junior restaurant critic – that I make the selfless decision about once a week to forsake my vegetarian principles, and try a spot of flesh on a plate.

This opens me up, I know, to the charge of moral laxity and hypocrisy. Let me plead guilty, then, and be done with it – except to say, briefly, that quite often I eat meat simply because it makes life so much bloody easier. Unlike other ethical choices you might make, such as becoming a vet or not punching the fat slob taking up too much room next to you on the bus, vegetarianism is a kind of moral visitation that occurs every time you eat. For me, this means about thrice an hour. Given all the other pressures in our lives, this additional stress is hard, really hard, and never more so than when eating socially.

The surest way, as I suspect you'll know, of ruining a dinner party is for a vegetarian to turn up. That's me. I'm that guy, the balding Indian who says he doesn't eat meat. Not just because of his Hindu heritage, with all the attendant affection for cows, but on grounds of animal welfare, ecology and health. And as I trot out these arguments for the umpteenth time – and even, if you're lucky, mention Franciscan Road – I find myself falling asleep. I'm boring myself. So let me level with you: the benefit in feeling good about my ethical choices is not always, or even often, greater than the cost in utter tediousness, social awkwardness or – worst of all – the charge of hypocrisy.

If you confess to being vegetarian, you see, you are immediately considered a ripe candidate not just for ridicule, but double standards. For vegetarians are expected to be faultless. "What's that, a leather belt you're wearing, while refusing my tagine? Outrageous!" "But Amol, do you use [insert brand name] soap? They were exposed for using whale-bladder offal in 1836 – and still you support them?"

Yes, guys. Yes, I do. I own leather belts and don't read up on what's in my soap. Sorry about that. As vegetarians go, I'm a late convert and a regular failure. Strong on principle, weaker in practice; but that, I humbly submit, is better than ducking the issue altogether. In any case, the hypocrisy of the bad vegetarian is infinitely preferable to the piety of the good carnivore. And whoever listened to a restaurant critic who didn't eat meat?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies