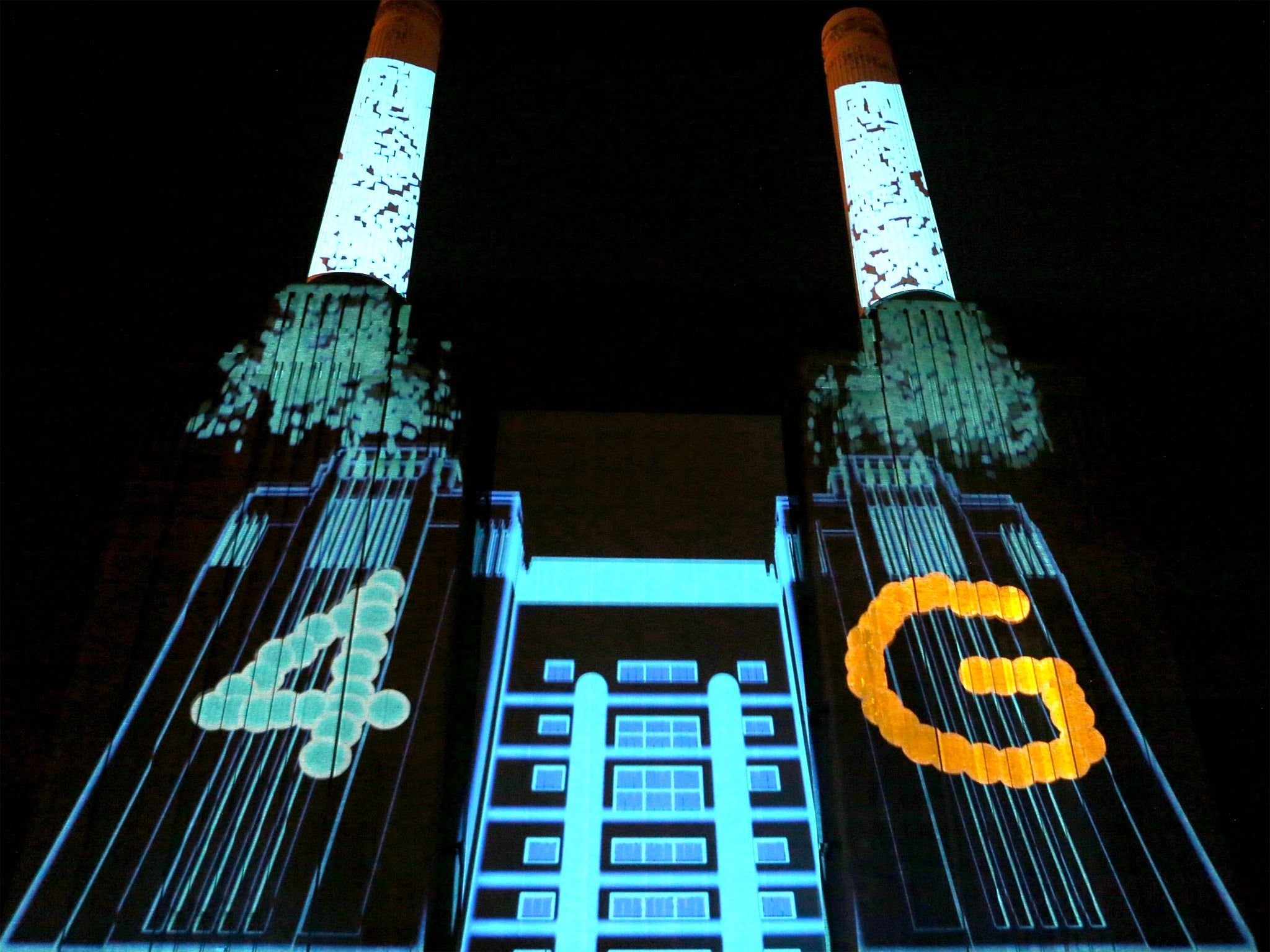

Battle of the bands: how the new 4G networks will differ

Mobile companies will use different airwave frequencies to offer 4G and this will impact on their service

Following the news that O2 will be launching its own 4G service on August 29, the fuss over the new network standard continues to confuse. And the difference is not only about costs - due to different companies using different parts of the radio spectrum to broadcast 4G, the services themselves will be varied.

For a start, the promise of 'superfast' speeds via 4G isn't so straightforward. EE have been reprimanded by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) for misleading consumers with their use of the word as its usually used in reference to fixed line internet connections offering download speeds of 24Mbps and upwards.

Whilst 4G will certainly be 'superfast' in comparison to 3G (probably around five times faster), it still doesn't offers download speeds equal to wired connections. Networks can always promise speeds of ‘up to’ some ridiculously high number, but such claims - whilst technically true - are usually false in practice.

EE’s attempts to hype up its network are understandable given its failure to take advantage of its early monopoly on 4G in the UK. The company was the first to offer 4G back in 2012 after petitioning Ofcom to convert some of its existing network capacity.

Other telecoms were taken off guard by the move, as most had expected to launch 4G services after Ofcom's planned auction of broadband spectrums in February 2013 (more on that later).

However, EE got greedy with its monopoly and launched its 4G network at extortionate prices. £31 for 3GB a month on a SIM only contract locked in for 24 months was one of their 'better' deals and unsurprisingly, customers didn’t bite, with revenues for the company falling 2% year on year.

Selling the airwaves

Following this false-start for 4G in the UK, the government auctioned off new portions of the airwaves in February this year, with telecoms buying them with the intent to launch 4G networks (though we should note that BT also bought some of the bands for non-4G purposes).

The auction was partly sparked by the closure of terrestrial television and the switch to digital, which freed up parts of the spectrum. Money was, of course, another motivating factor, and the sale raised £2.34bn; a large sum but still significantly smaller than the £3.5bn predicted by the treasury.

The idea of selling off something as intangible as Britain’s 'air' certainly strikes the imagination (‘New Low for Austerity Britain as Government Sells ‘Blitz Spirit’ to Saudi Royals’) but the companies are merely buying the right to broadcast at certain frequencies (full sales figures can be seen here).

Apart from creative possibilities of auctioning off abstract concepts, the frequency auction becomes very interest when you know that two different sorts of frequencies were being sold – bands around the 800MHz and 2.6GHz levels - will offer different sorts of 4G service.

How the spectrum varies

Activating 4G networks on the higher spectrum, the 2.6GHz band, will allow networks to offer higher download speeds – far better suited to urban environments where high number of customers will be ‘hogging the line’ as it were.

In comparison, the 800MHz band will be better suited for long-distance coverage and able to reach more remote parts of the country.

In the February auction O2 and Three only purchased sections of the 800MHz frequency (for £550m and £225m respectively) whilst Vodafone and EE bought into both the 800MHz and 2.6GHz ranges.

In theory, this might mean that O2’s service is worse for city-dwellers but will be available to a higher degree of the population (they're aiming for 98%, but then again, so are EE) whilst the opposite could hold true for EE.

It also means that EE will have the edge over O2 by being able to offer the iPhone 5. This model isn’t compliant with the 800MHz frequency but works perfectly well on the 1.8GHz band used by EE. Thankfully for O2 the forthcoming iPhone 5S will be compatible on all of these frequencies.

Despite this, it's not all to EE's advantage, as mobile experts have also said that the 800MHz range is far better suited for mobile data, which should mean less dropped video calls and the like, even if the speeds are slightly slower.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies