Cybercops: Keeping ahead of online criminals

Evil is stalking the internet, firing off vicious worms, phishing for bank details, and crippling vital networks. Rob Sharp watches the virtual detectives at work

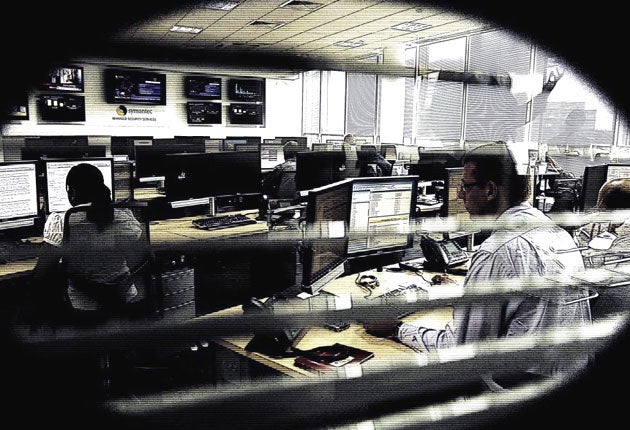

In an anonymous-looking business park just outside Reading town centre is a room where row upon row of specially trained computer analysts sit staring at a bank of screens. Several monitors display urgent-looking warnings. One shows a picture of a globe, spinning angrily. Another has close- ups of regions of the world highlighted as criminal "hotspots". These, my companions tell me, are areas vulnerable to attack from nefarious online activity.

As the names of companies coming under bombardment from web criminals scrolls down a third screen nearby, the overall feeling is disconcerting – it seems that no one is safe from this shifting, faceless enemy.

You could be forgiven for thinking this is the set of a hacker film like Sneakers. In fact, it is the UK operation, or nerve centre, of Symantec – one of the world's largest anti-virus companies, the owner of the Norton AntiVirus program, and the turn-to defence for global super-corporations trying to nip computer threats in the bud.

At the moment, the likes of Symantec have their hands full. The online community has seen an explosion in activity over the past 12 months as the quantity of "malware" (essentially, software designed to damage people's computers) has multiplied by a factor of five.

The reason, Symantec says, is the proliferation of organisations creating such software. These criminal clans hire programmers to create lucrative mechanisms for stealing credit-card information, and even sponsor computer science students through college. "A group of specialised [experts] can create a larger number of new threats than a single malicious code author can, bringing about economies of scale and therefore an increased return on investment," said a recent Symantec report.

Some modern malware can create download updates to make it change form and become harder to fight. It can also exploit the likes of Twitter and Facebook to lure people into giving out their bank details.

Symantec's security chief, Jim Hart, gives me a tour of the HQ. It is his team's job to respond to threats that might be facing Symantec's corporate clients. When detected, this army of some 30 minions issue patches and then inform their clients' internal IT departments of any security breaches.

"We are looking at criminal activity 24/7," Hart says. "What we do is health control. If we see one of the networks we are monitoring hook up to an IP address, this means there is data being transferred. And if that IP address is on our blacklist, we know that there is some kind of bad activity going on. This could be the theft of information or bank details. Then, for us, it's like a game of whack-a-mole. We see the infected machines and then we clean them – we hit the infections over the head."

Later, in a separate room, I meet one of Symantec's senior computer scientists, Guy Bunker, who has the Matrix-like moniker of "chief architect". He says that, while Symantec may be able to tell which servers or IP addresses are collecting such information, the location of these computers may not help track down those who are ultimately responsible.

"One of the main problems in trying to chase those behind viruses is that it tends not to be the people in the country that is doing the attacking," Bunker explains. "The villains might be using Chinese servers, but it could be someone in America pulling the strings. It is like giving someone a remote control and access over your machine, which they can then use to do their evil bidding."

He says malware has evolved to become smarter. To begin with, criminals – anyone trying to create spam, say, or to "phish" (to obtain bank-account information), could program a virus or malware from base code (the "building blocks" programmers use to create software). Now, people can send out a million versions of a virus. Each of these is subtly different from the last. Like human antibodies, which our bodies use to attack biological pathogens, many examples of virus detection software rely on recognising certain lines of code. If this code is constantly morphing, it becomes difficult to detect.

Some viruses can even download updates. In the "old days" people just did it to cause trouble – now, they are trying to do it to get money.

"The problem about tracking down the people behind these things is that they move around so quickly. Many of the servers used have a lifespan of only 10 days," Bunker says. "Some countries are better than others at shutting them down. The countries that host them tend to be the ones with looser internet security, or those that have just installed broadband and have not got fully operational security infrastructures up and running."

Peru has been fingered as a country at risk. One of the main reasons for this is that the country's broadband use has exploded over the past two years, and there is a lag between the installation of broadband and the use of online security programs. A similar issue was seen recently in Russia and China, which still have some of the highest incidences of online crime in the world.

Bunker explains how this "underground economy" of criminals has grown in size. "When I was on my first computer in the 1980s I spent hours typing in games from magazines," he says. "It's now the same with the growth of malware. Large teams of people are involved."

Someone who writes a successful piece of malware can earn as much as £170,000 on the black market, he says. Some may be sold for tens of thousands, but might yield cash totalling millions of pounds if those who buy the malware succeed in draining people's bank accounts.

Twitter is also a medium of attack. In this, anyone can sign up as a "follower", meaning that they can access people's details and indulge in identity theft. They also feature "tiny URLs" – essentially, shortened web-links that conceal addresses. "If you have a tiny URL you can't tell what it is – it could be a bit of malware, but you trust it and go 'I'll click on that,' but it could cause trouble."

Another escalating threat is online terrorism. How we deal with this needs an overhaul, says the think-tank Chatham House. "If society cannot respond in a similarly interconnected way, then the sum of security diminishes overall," says a cyberterrorism report to be published by the organisation next month.

This demonstrates how the web underlies the ideology of terrorism. "Extremists are attracted to a system that offers virtual anonymity," the report says. "They might also be attracted to a system that is relatively cost-free, and where the investments necessary to develop and maintain the global communications infrastructure have already been made – ironically by their enemies."

The solution? A self-governing network that is policed from within, apparently – something elastic enough to see off the challenges of the next 12 months, which will be as testing as anything seen in the previous year.

Intruder alert: The latest computer viruses

Koobface worm

Worms are self-replicating viruses that can spread through computer networks without any user intervention. One of the latest major threats is the Koobface worm, which targets MySpace and Facebook users (it's a thinly veiled anagram of the latter). It will post solicitous messages to the friends of an "infected" person, only to direct them to third-party sites where they will be prompted to download Adobe Flash player. If they download the file, they in turn will be infected with the worm.

Conficker worm

The most high-profile recent attack came from the Conficker worm, which infected about 15 million Microsoft server systems. Particularly vulnerable were unpatched Windows networks. Some 3,000 British institutions, including Royal Navy warships and submarines, and the Sheffield hospital network, were affected. Microsoft is offering a $250,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of the worm's creator.

Trojan horses

By far the most common virus threats are called Trojan horses. Named after the mythic gift to Troy, these programs can be downloaded unwittingly in the guise of a computer game, for example. Once on the host machine, they can allow unauthorised access or even remote use to a hacker. One of the latest incarnations, Trojan.Pidief.E, works simply by fooling the user into opening an infected PDF file.

MyTob

In November 2008, three London hospitals, including Barts, had to shut down their computer systems for 24 hours when they were struck by the MyTob worm. Ambulances were diverted from Barts for hours, and many administrative, laboratory and imaging tasks had to revert to manual operation. It took more than a week to eliminate the infection.

Devkit

Valentine's Day provides hackers with an opportunity to infiltrate using so-called "social engineering" tactics. In this case, two cute puppies hold a heart in their mouths, while the blurb exhorts the user to download a "Valentine's Devkit" for wooing their beloved. The Devkit is actually a piece of malware.

Alex Rousso

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies