'Smart factories' where products 'talk' to each stage of the production process are the next big thing in automation

Rebecca Rose Jacobs sees the industrial internet at work

Busy day? A million things to do? Well, here's depressing news: you'll probably mess up about 5,000 of them. That's what the research shows: for every million mechanical tasks a human performs, most of us insert mistakes into the execution about 5,000 times. It might seem a lot, but think of the number of emails you send containing a typo, the number of dishes that make it to the drying rack with a fleck of food still on them, the mismatched socks you spot only at lunchtime... and then consider that you're operating at a failure rate of a mere 0.5 per cent. Not bad, right?

That might have been what the managers of a Siemens factory in Amberg, Germany, thought 25 years ago, when looking at their defects per million rate (a common quality measure in industry). The plant, which made controllers – the boxes stuffed with circuit boards and switches that act as brains for other factories around the world – was already doing much better than the average human, at 550 defects per million.

But to the team there, even that number seemed too high, particularly as a broken controller can shut down a factory, costing its owners millions of dollars per day in lost production. And so Siemens began moving the factory toward a more automated future, counting on computers to beat humans in the race for quality. In 1990, 25 per cent of the shop floor was automated; today, it's 75 per cent. And the defect rate has dropped sharply – to 11.5 per million. Output, meanwhile, is 8.5 times higher, while employee numbers and floor space stayed steady.

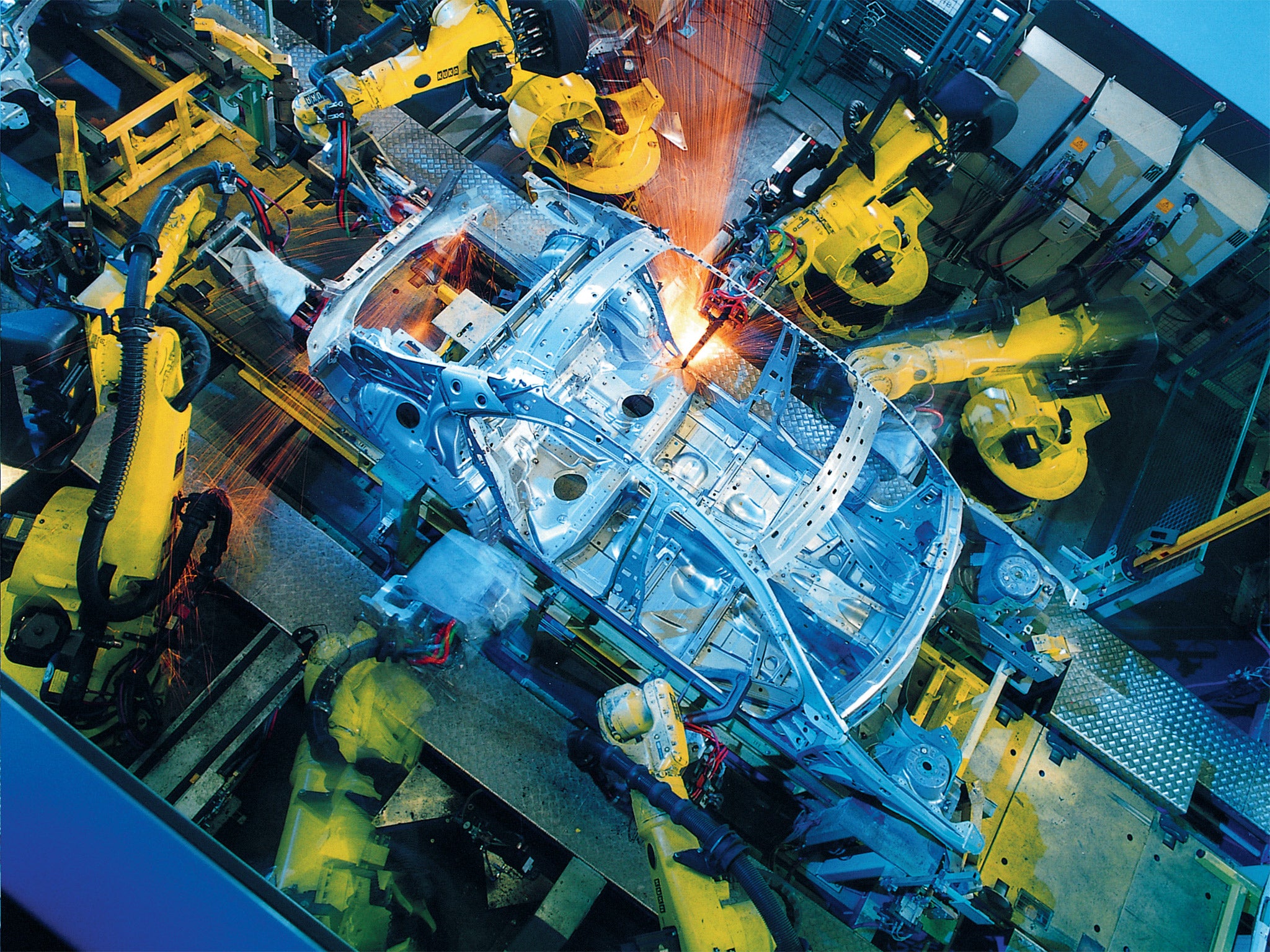

Amberg, about 25 miles west of Nuremberg, has become a showcase for automation. German Chancellor Angela Merkel visited in late February and called it an example of Germany's wealth of "ideas and well-educated workers". But more important is what the plant says about the future. It is Siemens' testing ground for a huge development in automation, where digitised factories are less the setting for a series of sequential steps and more like networks in which assembly lines communicate not just with one another or within the company but with systems elsewhere, and with the very products being produced. The newly struck hood of a car-to-be rolls up to the paint machine and tells it, "I should be blue." The next one sends the message that it prefers silver.

In Germany, the engineers and academics working to create this "fourth industrial revolution" call it Industrie 4.0; in the US, it's referred to as "the industrial internet". General Electric describes it as "the tight integration of the physical and digital worlds... [enabling] companies to use sensors, software, machine-to-machine learning and other technologies to gather and analyse data from physical objects or other large data streams – and then use those analyses to manage operations."

You might expect a world built on sensors, software and machines to be devoid of humans. But in Amberg, the 30,000sq ft shop floor is populated by 1,020 workers over three shifts. And despite all the computers around, their labour still appears to be (mostly) physical: a young man lying on his back inches his way under an elegant blue and grey machine, as you would under a car needing repair; a woman nearby bends over a circuit board wielding tweezers. Other members of staff peer at screens, never touching the products rolling down glassed-in assembly lines.

"A digital future can frighten people," says Gunther Ziebell, a production unit leader in Amberg. "But we complement automated tests with eye checks."

What's more, the project has not only maintained workforce numbers, it has created demand for more experienced and creative employees. The management structure in Amberg has become very flat, allowing, for example, line workers to speak with the IT department directly rather than go through their bosses. Any employee can initiate a project that requires an investment of less than £8,000, and earns a bonus when he or she suggests changes that are later implemented. The average employee makes an additional £750 per year this way, says Ziebell, adding that "if a digital factory is being managed top-down, you wouldn't get many advantages from it". Hierarchies hold back creative potential, he argues. Just as open-access software evolves more quickly than that developed in controlled, restrictive environments, so open-access work processes will improve more quickly than those dictated by bosses.

But even if increasing automation hasn't led to lost jobs in Amberg, fast-growing efficiency means new plants that might have been built to meet rising customer demand – and new positions to fill them – are now unnecessary. It is an issue the Germans, at least, are attempting to address head-on, with plans under way to form an Industrie 4.0 national-level working group that includes employee representatives as well as private businesses and industry bodies.

Dieter Wegener, Siemens' coordinator for Industrie 4.0, argues that companies aren't pushing these developments; consumers are. We want customised products, he says, we want them now, and we want them made efficiently, in order to both bring down prices and preserve natural resources. This isn't possible without networked production processes.

There are other serious challenges that must be overcome for digitisation to have a significant impact on profit margins or market share. For example, there needs to be some standardisation across industries: it doesn't do much good for your soda bottle to speak to the bottling machine filling it if they're speaking different languages. A survey by the consultancy Accenture last year found that a third of companies eager to embrace "the industrial internet" cited "consolidation of disparate data" as a serious concern.

Security was another top worry. Technicians at Siemens' HQ in Munich have recently started hacking into the Amberg factory's systems, test runs for the potential real deal. Still, to take full advantage of "smart factories", every link in the supply chain must be secure. That creates a conundrum: taking full advantage of "smart factories" also involves a democratisation of information, and in Amberg any employee can see the real-time data pouring in about each product on the line. Companies will need to find a balance between transparency and security.

For Wegener, a third challenge is making sure that Big Data isn't tapped simply for the sake of tapping Big Data. It has to add value to each operation in a sector-specific way. "There's no benefit to making something smart," he says, "without it making sense."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies