Doctor William Cullen's Enlightenment-era letters to be made available online

Samuel Johnson and a Russian princess were among physician’s corresponding clients

Weighing in at 16 stone and plagued by a persistent cough in 1780, Jane Webster was badly in need of written advice from Doctor William Cullen. In return for a fee equivalent to £250, she was duly told: “Corpulence certainly disposes to violent diseases… You must take a great deal of bodily exercise.”

Other patients seeking counsel by letter from perhaps the foremost medic of his age included a Russian princess with gout, a Scottish plantation owner seeking a cure for a slave’s epilepsy and one unfortunate lady in need of urgent aid for the effects of excessive cucumber consumption.

Between the mid-1750s and his death in 1790, the good doctor received and sent some 5,000 letters as he conducted a lucrative trade in medicine by mail from his Edinburgh home.

The resulting archive of Enlightenment medical practice has hitherto only been accessible by visiting the Scottish capital but as of 11 May it becomes available online to offer a unique insight into the world of 18th-century healing.

A digitised version of the vast quantity of letters and responses gathered by the Scottish medic will be launched on 11 May at the Royal College of Physicians in Edinburgh after a four-year project by Glasgow University to copy and catalogue his cases.

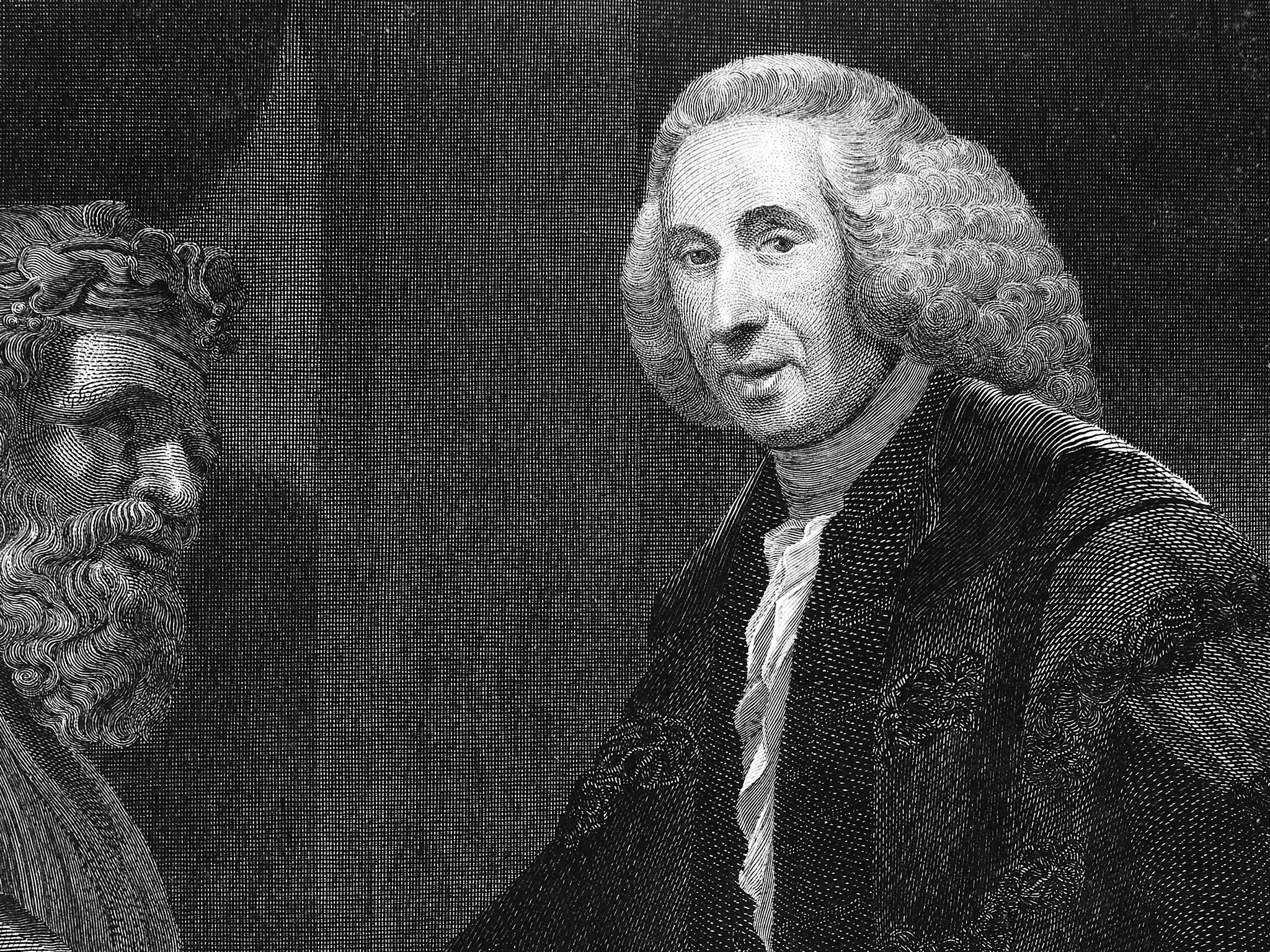

Born in modest circumstances, Dr Cullen rose to become one of the most eminent and best-known physicians of his era, becoming a professor at Edinburgh University and popularising his teaching by - unusually for the time - delivering his lectures in English rather than Latin.

As his fame spread, the professor also developed a burgeoning private practice with patients from across the world writing in search of treatment for a multiplicity of ailments.

Dr David Shuttleton, a medical culture lecturer at Glasgow University, who led the project, said: “Medicine by post was common in the 18th Century. Travel was difficult, physical diagnosis rudimentary and laboratory medicine non-existent. As a result a fair description of somebody’s complaints was thought sufficient for a tentative diagnosis and the institution of treatment.”

The services of Dr Cullen, who awoke at 6.45am each day to write his mail order prescriptions and ensured most enquiries were answered within a day, did not come cheap. His standard fee was two guineas - equivalent to £250 today - though he offered sharply discounted rates to widows, students and clerics.

His clients ranged from the obese Mrs Webster to a Stranraer customs official suffering depression to a dying Samuel Johnson, whose friend and biographer James Boswell wrote seeking advice on his behalf.

Though Dr Cullen was given to some unorthodox treatments, including a particular fondness for cold showers and leeches, many of his prescriptions would be recognised by modern GPs as he advised his patients to pay attention to their diet, exercise regularly and take care of their psychological well being.

Dr Shuttleton said: “In his private practice, he was very much in the ancient Greek tradition of preventative medicine through lifestyle. He was very keen on patients managing their health through a regimen.”

The archive, accessible via the Cullen Project website, is expected to act a resource not only for medical history aficionados but also students of postal history.

The collection contains a remarkable diversity of postal markings, incl

uding some which show that for patients in the Orkney or Shetland Islands there was often a gap of several months between a sufferer sending a letter and receiving Dr Cullen’s reply due to the slowness of transport.

Case study

In 1778, Patrick McIntyre, Comptroller of Customs in Stranraer, wrote to Dr Cullen complaining “my mind is continually full of terror and much anxiety, and I find my mind gloomy and melancholy to the last degree”.

The doctor, noting Mr McIntyre had confessed to using “my Bottle rather too freely”, replied: “With respect to strong drink I would not bid you abstain from it altogether, but it is absolutely necessary for you to be very moderate.

“A full bottle may seem to give you temporary relief, but every degree of excess with certainly make your ailments recur with more violence.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies