Sign up to our free Living Well email for advice on living a happier, healthier and longer life Live your life healthier and happier with our free weekly Living Well newsletter

Maybe it was because Samuel has the same name as my son, now a man, or because he is the same age as my eldest grandson, eight – or just because of his ready smile and gentle, friendly nature – but something about this little boy captured my heart.

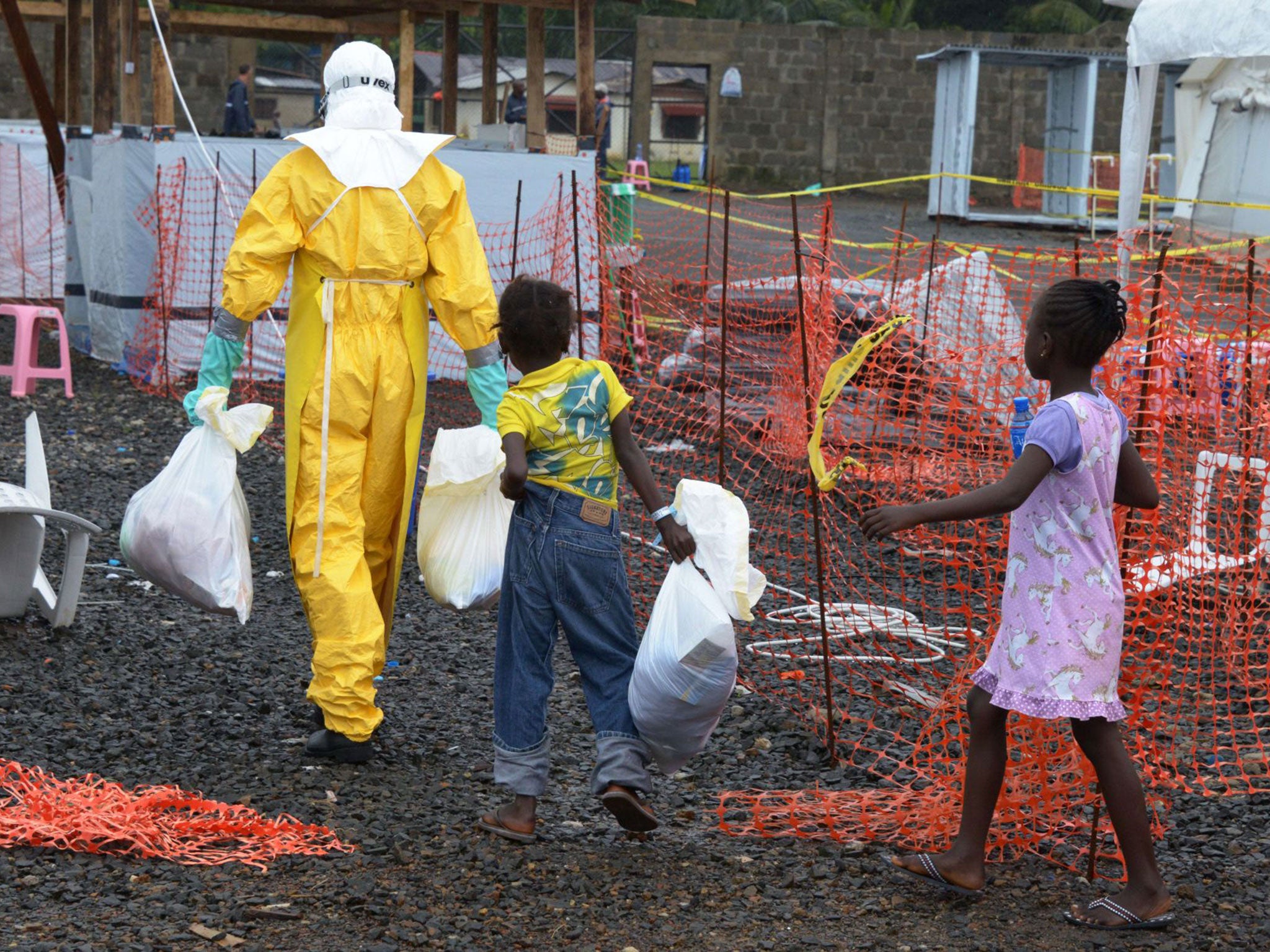

He came with his mother from outside Monrovia, no one knows from exactly where, but when his mother died from Ebola in our treatment centre in the city, called Elwa 3, we had no information about his remaining family and no way to contact them, so he ended up in the "hotel" tent.

The people in the hotel tent, based inside the centre, are those who are cured and those who have tested negative for the virus but the lab results came in too late in the day to organise transportation home. They stay overnight in the tent and are then taken home by relatives or in our taxi the next day.

Show all 62 1 /62In pictures: Ebola virus In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A health worker from Sierra Leone's Red Cross Society Burial Team 7 carries the corpse of a child in Freetown

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A health workers from the Sierra Leone's Red Cross Society Burial Team 7 is sprayed with desinfectant after removing a corpse from a house in Freetown

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Health workers from Sierra Leone's Red Cross Society Burial Team 7 prepare to remove a body from a house in Freetown

AFP

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Health workers from the Sierra Leone's Red Cross Society Burial Team 7 place a body in a grave at King Tom cemetary in Freetown

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Mustapha Rogers of the Red Cross talks as health workers from the Sierra Leone's Red Cross Society Burial Team 7 remove a corpse from a house in Freetown

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A citizen from Mali arrives at a hospital in Murcia city, south-eastern Spain. The protocol for a possible case of Ebola has been activated as the man, who arrived from Mali to Jumilla town in Murcia province five days ago, presents clinical symptoms of high fever and vomiting

EPA

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Kenyan medical workers show how to handle an infected Ebola patient on a portable negative pressure bed at the Kenyatta national hospital in Nairobi

Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A health worker sprays disinfectant onto a college in Monrovia, Liberia

AP

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A burial team in protective gear bury the body of a woman suspected to have died from Ebola virus in Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Healthcare workers in protective gear work at an Ebola treatment center in the west of Freetown, Sierra Leone

AP Photo/Michael Duff

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A healthcare worker in protective gear is sprayed with disinfectant after working in an Ebola treatment center in the west of Freetown, Sierra Leone

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A member of the NGO U Fondation leaves a house after visiting quarantined family members suffering from the Ebola virus in Monrovia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus An Ebola sign placed infront of a home in West Point slum area of Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A Liberian man carries his sick brother suspected of having Ebola after being delayed admission to the Island Clinic Ebola Treatment Unit due to a lack of beds at the clinic on the outskirts of Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Health workers remove the body a woman who died from the Ebola virus in the Aberdeen district of Freetown, Sierra Leone

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A health worker fixes another health worker's protective suit in the Aberdeen district of Freetown, Sierra Leone

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Health workers spray themselves with chlorine disinfectants after removing the body a woman who died of Ebola virus in the Aberdeen district of Freetown, Sierra Leone

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A woman crawls towards the body of her sister as Ebola burial team members take her sister Mekie Nagbe (28) for cremation in Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Sophia Doe sits with her grandchildren Beauty Mandi, 9 months (L) and Arthuneh Qunoh, 9, (R), while watching the arrival an Ebola burial team to take away the body of her daughter Mekie Nagbe, 28, for cremation in Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Varney Jonson (46) grieves as an Ebola burial team takes away the body of his wife Nama Fambule for cremation in Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Family members grieve as Ebola burial team members prepare to remove the body of Nama Fambule for cremation in Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A Liberian burial squad carry the body of an Ebola victim in Marshall, Margini county, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus An Ebola burial team dresses in protective clothing before collecting the body of a woman (54) from her home in the New Kru Town suburb of Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus An Ebola burial team carries the body of a woman (54) through the New Kru Town suburb of Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus An Ebola burial team dresses in protective clothing before collecting the body of a woman (54) from her home in the New Kru Town suburb of Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Health workers in protective gear carry the body of a woman suspected to have died from Ebola virus, from a house in New Kru Town at the outskirt of Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Volunteers in protective suit bury the body of a person who died from Ebola in Waterloo, some 30 kilometers southeast of Freetown

FLORIAN PLAUCHEUR/AFP/Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Nowa Paye (9) is taken to an ambulance after showing signs of the Ebola infection in the village of Freeman Reserve, about 30 miles north of Monrovia, Liberia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Medical staff members burn clothes belonging to patients suffering from Ebola, at the French medical NGO Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) in Monrovia

PASCAL GUYOT/AFP/Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A medical staff member wearing a protective suit walks past the crematorium where victims of Ebola are burned in Monrovia

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A Liberian burial team wearing protective clothing loads the body of a 60-year-old Ebola victim after retrieving him from his home

Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Sick women rest while hoping to enter the new Doctors Without Borders (MSF), Ebola treatment center near Monrovia, Liberia

Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Hanah Siafa walks in the rain with her children Josephine, 10, and Elija, six, while waiting to enter the new Doctors Without Borders (MSF), Ebola treatment center in Monrovia, Liberia

Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus UNICEF health workers walk through the streets, going house to house to speak about Ebola prevention in New Kru Town, Liberia. The virus has killed more than 1,000 people in four African countries

Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Local residents watch as public health advocates stage an Ebola awareness and prevention event in Monrovia, Liberia

Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Public health advocates stage an Ebola awareness and prevention event in Monrovia, Liberia. The Liberian government and international groups are trying to convince residents of the danger and are urging people to wash their hands to help prevent the spread of the epidemic

Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Hanah Siafa lies with her children Josephine, 10, and Elija, six, while hoping to enter the new Doctors Without Borders (MSF), Ebola treatment center

Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A health worker examines patients for Ebola inside a screening tent, at the Kenema Government Hospital

AP

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A health worker cleans his hands with chlorinated water before entering an Ebola screening tent at the Kenema Government Hospital, about 86 miles from Sierra Leone’s capital Freetown

AP

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Aid workers and doctors transfer Miguel Pajares, a Spanish priest who was infected with the Ebola virus while working in Liberia, from a plane to an ambulance as he leaves the Torrejon de Ardoz military airbase, near Madrid, Spain

AP Photo/Spanish Defense Ministry

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A Liberian money exchanger washes hands between customers as a precaution to prevent infection with the deadly Ebola virus while conducting business in downtown Monrovia, Liberia

EPA

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A Liberian health worker sprays disinfectant on a drivers boots to stop the spread of the deadly Ebola virus at the Christian charity Samaritan Purse head offices in Monrovia, Liberia. Over 660 people have died of Ebola in West Africa in 2014 making it the world's deadliest outbreak to date according to statistics from the World Health Organisation

EPA

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A Liberian taxi driver wears protective gloves as a precaution to prevent infection with the deadly Ebola virus whilst driving in downtown Monrovia, Liberia. Many Liberians have taken to wearing gloves and washing hands after every interaction in an attempt to curb the spread of the deadly virus

EPA

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A Liberian money exchanger wears protective gloves as a precaution to prevent infection with the deadly Ebola virus while transacting business with customers in downtown Monrovia, Liberia

EPA

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A woman from Liberia takes food to a sick relative in the Ebola isolation unit at the ELWA Hospital where US doctor Kent Bradley is being quarantined having contracted the Ebola virus. Over 660 people have died of Ebola in West Africa in 2014 making it the world's deadliest outbreak to date according to statistics from the World Health Organisation

EPA

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus The disease has now spread to Liberia and, for the first time, Sierra Leone and Nigeria, killing at least 672 people in 1,201 cases, according to the World Health Organisation’s latest figures

AP

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Health specialists prepare for work in an isolation ward for patients at the Medecins Sans Frontieres facility in southern Guinea

AFP/Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A Liberian street vendor wears protective gloves as a precaution to prevent infection with the deadly Ebola virus while transacting business with customers in downtown Monrovia, Liberia

EPA

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A nurse from Liberia sprays preventives to disinfect the waiting area for visitors at the ELWA Hospital where a US doctor Kent Bradley is being quarantined in the hospitals isolation unit having contracted the Ebola virus, Monrovia, Liberia

EPA

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Staff of the 'Doctors without Borders' ('Medecin sans frontieres') medical aid organisation carry the body of a person killed by the virus

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A Liberia man (right) talks to a nurse (left) about the health of his relative who is in the isolation unit of the ELWA Hospital where a US doctor Kent Bradley is being quarantined having contracted the Ebola virus, Monrovia, Liberia

EPA

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A nurse from Liberia walks to spray preventives to disinfect the waiting area for visitors at the ELWA Hospital where a US doctor Kent Bradley is being quarantined in the hospitals isolation unit having contracted the Ebola virus

EPA

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Staff of the Christian charity Samaritan's Purse put on protective gear in the ELWA hospital in the Liberian capital Monrovia

AFP

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Lagos State Health Commissioner Jide Idris, speaks, during a news conference in Lagos, Nigeria. No one knows for sure just how many people Patrick Sawyer came into contact with the day he boarded a flight in Liberia, had a stopover in Ghana, changed planes in Togo, and then arrived in Nigeria, where authorities say he died days later from Ebola

AP Photo/Sunday Alamba

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Staff of the Christian charity Samaritan's Purse put on protective gear in the ELWA hospital in the Liberian capital Monrovia. An American doctor battling West Africa's Ebola epidemic has himself fallen sick with the disease in Liberia, Samaritan's Purse said

AP

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Protective gear including boots, gloves, masks and suits, drying after being used in a treatment room in the ELWA hospital in the Liberian capital Monrovia

AFP

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A Liberian man holding a Civet being sold on a roadside as bush meat in Lofa County. Bush meat is one of the major carriers of the Ebola virus. The Liberian government and International partners have warned people to not eat it. The World Health Organisation (WHO) reported that a total of 888 Ebola cases including 539 deaths have been recorded in West Africa since February

AFP

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus People unload protection and healthcare material at Conakry's airport, to help fight the spread of the Ebola virus and treat people who have been already infected

AFP/Getty Images

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Body of evidence: health workers transport a casket of a nun whose death resulted from an Ebola infection in Zaire in 1995

Getty

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Peter Piot in Yambuku, northern Congo (then Zaire), in 1976, where he was part of the original team to discover the Ebola virus

J Breman

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus A member of Doctors Without Borders helps to unload protection and healthcare materials in Guinea

Getty

In pictures: Ebola virus Ebola virus Doctors in protective gear work inside the Medecins Sans Frontieres isolation ward as Guinea faced the worst ever outbreak of the Ebola virus

Getty Images

However, more and more often we end up with children whose parents are sick in the treatment centre, but they have not contracted the disease themselves. Or those whose parents have died and we have no details of extended family. Or those whose family have rejected them through fear of Ebola.

Samuel fell into the middle category. Initially he had the company of a few other children and they seemed to be having great fun playing with each other and with the toys we had found for them.

Slowly, the number of these children dwindled as relatives were traced, until finally Samuel was sat all alone – no one to play with and no one in the world to love or look after him.

All through this, Samuel sat, smiling bravely when anyone spoke to him, while our support unit desperately searched for someone, somewhere who we could send him to. I sat with him and we drew pictures – his smile and laughter were infectious, and quite amazing considering his circumstances. We have a no-contact policy, so I couldn't even give him a hug, but he seemed to enjoy any company, no matter how limited. He was a delightful boy: polite, eager to learn, and utterly charming.

Eventually the authorities managed to match him with a person who had survived Ebola, but I heard that the community they were placed in would not accept their presence due to the fear of Ebola, and they had to be moved.

I didn't see Samuel to say goodbye. One day he was there and the next gone. I try not to think about him. I should know better than to become too fond of anyone who comes to our centre. It makes working here harder because stories of tragedy lie behind all the dead in our morgue.

I make sure I stick to my job – infection control – I check the protocols are observed and make sure that, as much as possible, there is a safe working environment.

The hotel tent continues to fill with babies and small children, and we see only the tip of the iceberg. There must be many more like them in the community who have no one to find them a home.

Cokie van der Velde is a sanitation specialist with Médecins Sans Frontières. You can make a donation to help MSF's work at msf.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies