Overtaken by events: how will we cope with the driverless car?

It may save lives, but most of us will draw in our breath sharply when it accelerates

If you live in a city, step outside your front door and look around. Consider the construction of your environment. What are the fundamental principles in play? How has the world been planned?

This is a hard question to answer, because the truth is so obvious and fundamental that one doesn't notice it. But I think it's this: your environment is designed so that you can easily navigate it. It isn't built for comfort, or there would be sofas in the streets; it isn't built for our aesthetic edification, or there would be mosaics on the pavement. It isn't built for safety or sustainability. It's built for speed. It's built so you can get from A to B as quickly as possible. And, these days, most of the time, for most of us, that means: by getting in a car.

Even for those of us who don't own one, the car is a critical prop of modern life, one of a very few things the transformation of which would make the world alien. (Smartphones and the growth of online retail are the only such game-changers I can think of in recent years.) And its evolution has been sufficiently slow that one hardly pays attention to it or imagines how else it might be: if you were to switch your mobile, your computer and your car for a 20-year-old model, I think the car's the only one where you could live with the difference. No one texts on a vintage Nokia, or sends their email on a classic Amstrad: whatever romance they might have had has been extinguished by their incompatibility with modernity. And yet a 1995 Corsa will comfortably get you to work.

That stasis breeds conservatism, and an assumption that it will continue for ever. But, last week, Vince Cable issued us with a firm reminder that it won't. From January, driverless cars will be allowed to test on public roads, he announced; cities will be invited to bid for the chance to host trials, and the rules of the road will be reviewed to ensure they are fit for the hoped-for revolution. The move would be revolutionary, he said, "putting us at the forefront of this transformational technology and opening up new opportunities for our economy and society".

To which many of us will, I think, say: hang on a second, Vince. Do you really expect us to entrust our fate, in a speeding two-ton metal box, to the vagaries of the same technology that sits in our laptops? Computers might be good at repetitive tasks, but driving is a dynamic business, a constant management of risk and progress; no computer could know when to nudge forwards at a junction, or when to sneak into the other lane. This isn't draughts, it's three-dimensional chess. We're good at it because we have instincts and experiences that equip us to manage it better than a robot ever could.

The thing is, though – as it turns out, we're not really all that good at it. In 2010, the last year for which data is available, some 1.24 million people died in road accidents around the world. And the evidence of the many trials going on across the globe, pre-eminent among them the experiments being carried out at Google's headquarters in California, is that some prototypes are probably already a safer bet than the piloted alternative; in a decade's time, the difference will be a chasm. Some car companies are aiming to have fully automated vehicles on the market within five years. While the predictions are naturally a bit cloudy and varied, most analysts expect the majority of new cars to be driverless by the early 2030s.

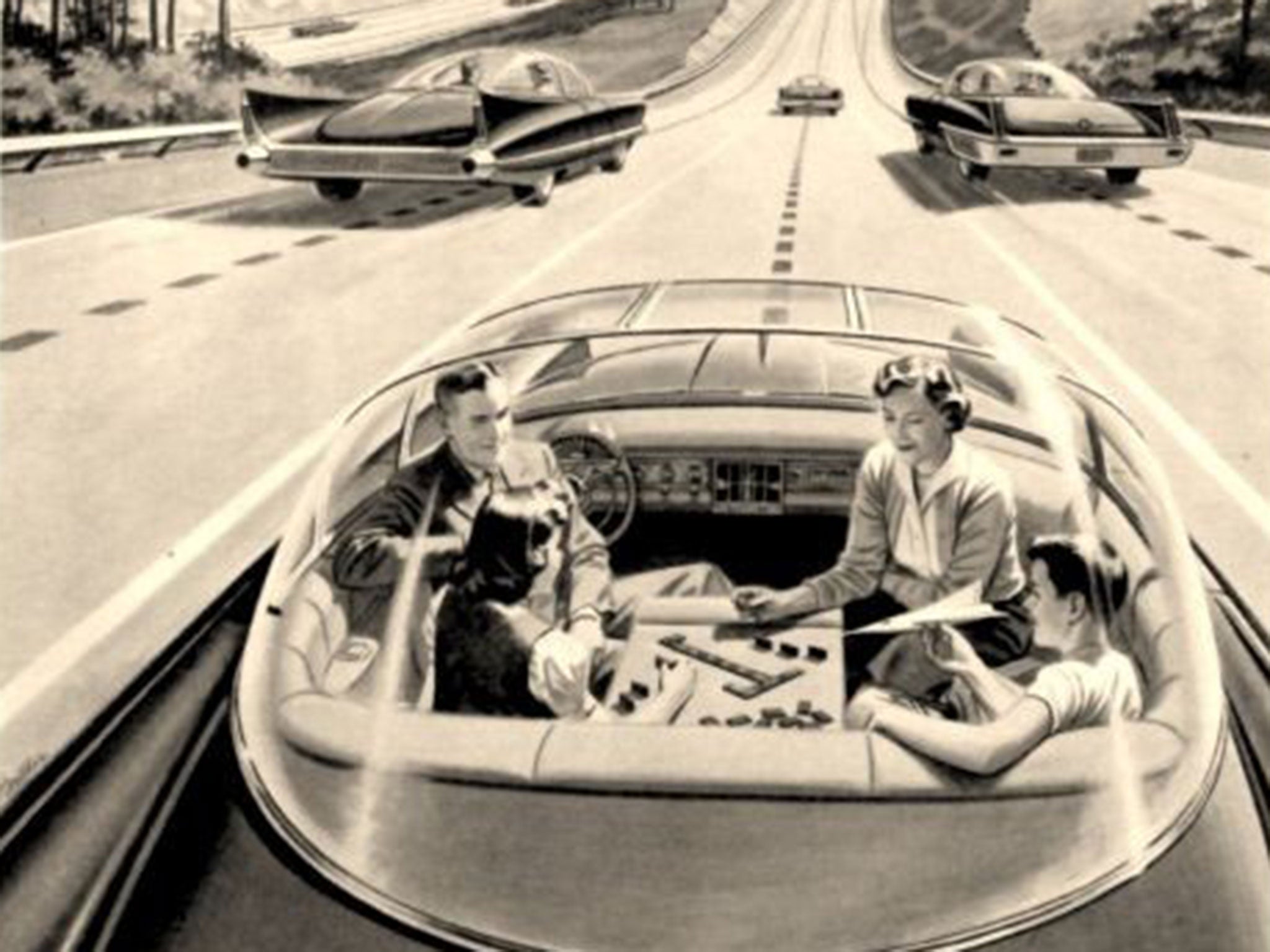

Then again, those predictions might best be taken with a pinch of salt. Driverless technology seems to have been on the cusp of becoming a reality for decades and yet has never quite materialised. As early as 1932, a newspaper in Fredericksburg, Virginia, was proclaiming that a "phantom auto" would soon be operated there, "controlled entirely by radio" and "proceeding just as though there were an invisible driver at the wheel". "It sounds unbelievable," the reporter marvelled, "but it is true."

That such gimmicks have never translated to a practical reality is partly a matter of technological obstacles. But experts also say that a governmental failure to invest more has a lot to do with it. And I wonder if that failure is to do with something that is, on one level, a little silly: fear. Driverless cars in pop culture, after all, are generally nightmarish, whether they are popping up in Stephen King novels or films such as Minority Report. Isaac Asimov wrote a short story set in 2057 about driverless cars, called Sally, in which the narrator comes to fear they may take over the world after one deliberately kills a man. "There are millions of automobiles on earth," he frets. "Tens of millions. If the thought gets rooted in them that they're slaves … they wouldn't kill us all. But maybe they would." This might be a little extreme, but it speaks to a common strain of technophobia: we don't like to lose control of our fates, even if it's to an infinitely more reliable judge than us.

And there are other things we will lose when driving ceases to be normal, things we barely notice today. We'll lose one of the few quotidian activities that demand, perhaps on pain of death, our absolute focus, even if it means we can't check our email; the pleasures of speed will become luxurious and lulling, instead of giddy, raw, even subversive. The parent who counts on the car as the one place she can talk to her teenager frankly may find that the ability to make eye contact makes him clam up; the traveller whose sense of a place is built in part by how he navigates it will find another normalising layer of cotton wool inserted between him and the exotic. And all of us, at least for a while, will sharply draw breath when our automated chauffeur overtakes. All sorts of strange new problems, ethical and practical, will arise. Will there be a way to go faster just because we're late? If a child is in the road and a carload of pensioners is coming the other way, will the computer be programmed to swerve or carry on?

It's still a way off, of course. And, when it comes, it will become normal more quickly than we could ever imagine, just as seismic change always does. It's worth remembering: for each of those practices that we will lose, another will arise in its place. Lives will be saved, car parks won't be needed if our vehicles can potter home after delivering us to work or the shops. And, perhaps, with our Clarksonite tendencies neutered, we will start to look at our cities with fresh eyes. Instead of being places to navigate, they might become places to live.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies