How to keep down the costs of your child's private education

Schools are putting a lid on their fees but parents are still finding it hard to afford them. Neasa MacErlean offers some tips on saving money

Private schools are keeping their fee increases this year to historic lows but, even so, many parents of the 500,000 children enrolled in this sector will struggle to meet the payments. So how can costs be kept down? One trick which parents could miss at the outset is the low-profile school which offers far more value than might be expected. "A school can be outstanding in every category of inspection and have low fees," says Neil Roskilly, chief executive officer of the Independent Schools Association.

"Parents should check inspection reports carefully, as they could find that a lesser-known private school in their area could provide great value for money and also offer an excellent potential outcome for their child."

One such school is Oakhyrst Grange, a co-ed prep school with 150 pupils in Caterham. Its early years section has been rated as outstanding in the last two Ofsted inspections; its older classes are all outstanding or good; nearly a quarter of leaving pupils get scholarships or other awards; and it has a three-year waiting list. Its fees this year range, by age, from £2,024 per term to £2,450. These rates bring it in £500 lower per term than similar schools in the area. "We're a charitable trust," says headmaster Alex Gear. "We have no debts or borrowing. All the money we make is reinvested into resources, first and foremost staffing and then new buildings or IT."

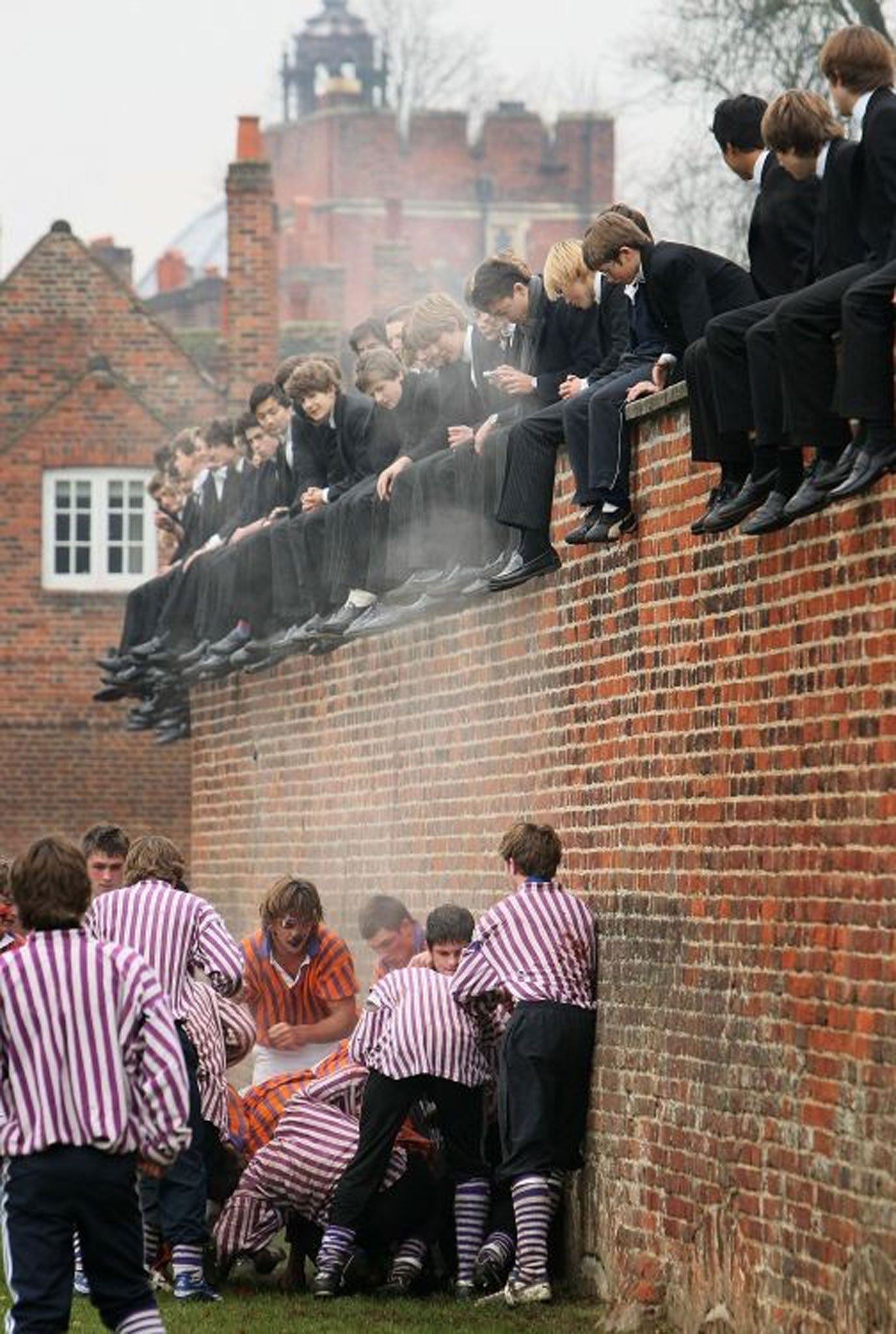

Eton College, the school David Cameron attended, is charging £11,090 a term this year and Harrow will charge £5 more. Boarding fees are built into these prices. But much of the rest of the cost relates to "extras", mainly in sports and culture.

Fees this year are typically going up by 3 to 3.5 per cent, according to the Independent Schools Association. But, Mr Roskilly says, "there's a lot of variation". Pupil numbers are falling slightly. There were over 506,000 pupils in the sector in 2012, and 504,000 in 2013, according to the Independent Schools Council. Most of the drop relates to a fall in boarders.

Parents on a tight budget will soon discover that a third of pupils in private schools receive some form of contribution, typically worth £4,000. This can be a big help towards school fees which, in Greater London, for instance, average £4,600 a term. The most common fee reduction comes through bursaries. There are also scholarships and then other discounts given as means-tested awards. "Siblings and other discounts are worth negotiating," says Mr Roskilly.

Fee levels vary considerably by region. The Independent Schools Council's Census 2013 data show fees in the north average £3,054 a term, a third less than the London rate. That gap could widen in future, as demand is increasing in London, the south-east and East Anglia but has fallen nearly 10 per cent since 2007 in the north.

Certain types of school are faring better than others. Single-sex girls schools in the more remote locations are not generally flourishing in the way that co-ed is. Many girls schools have experienced a slow and steady decline in numbers, so parents may find the door ajar if they want to negotiate on fees. Data from the Girls' School Association suggests a fall of about 1 per cent in numbers between 2011 and 2013.

When parents are researching schools a useful question to ask is the amount of debt that an institution has. If Oakhyrst Grange sees its lack of debt as an important factor in its success, then other schools could be vulnerable by being dependent on the banks. When a bank decides to revalue a school's biggest financial asset, its premises, the new valuation these days will often reveal a slump in value since loans and overdrafts were last agreed. If the figures do not match up well, it is up to the bank to decide whether to pull out the rug. "This is because of the banks' need to recapitalise," says Mr Roskilly. "They see schools as a soft touch."

But some new, interesting owners are entering the market – specialist venture capitalists, for instance, which have often made a notable success of these educational projects.

Parents may worry that schools with financial difficulties will let their standards drop, by recruiting fewer teachers, perhaps, or spending less on facilities. However, the Independent Schools Association reports a substantial 15 per cent increase of £100m in capital expenditure in 2012-13. Many schools will be seeking to refurbish existing buildings rather than to build new ones but the costs incurred are still significant. IT spending is pretty much a necessity on a regular basis, as technology is developing so fast.

The financial climate in state schools is also changing. More children are qualifying for free school meals. But, teachers report, this does not create embarrassment in the classroom. "The benefits culture isn't looked down on these days," says a London junior school teacher. "It's the reverse." So more children get free uniforms and trips as well as free meals. "I've never seen any embarrassment," she continues, talking about the eight-year olds she teaches.

A positive trend in the state sector could come from the alumni system starting to be created. Following the success of such schemes at Eton and Harrow, which have helped fund those schools for hundreds of years, some state schools are setting up their own. The charity Future First is working with over 500 schools on these schemes. It estimates schools can typically unlock the best part of £30,000 of donations in a year. And some of the contact with alumni of senior schools in tough areas has produced dramatic results.

When pupils meet alumni who have done well in the workplace, about 80 per cent of the children come out more motivated regarding their work prospects and say they are going to study harder.

Battling a divorce: A tough fight to see her kids through, but worth it

Sally has had to fight hard to see her daughter and son through their private boarding school but she is delighted that she did.

"The pastoral care was over and beyond what you'd expect," she says. "That's what boarding schools are for – amazing role models who are truly compassionate." The children were suffering from the backlash of a nasty divorce, and their father did not want them to continue at the school. But in the court deliberations, the judge largely sympathised with Sally (not her real name) on the question of education. The judge ordered the couple to pay the school fees in advance out of the proceeds of the sale of the family home. "The school gives you a discount for paying up front," explains Sally.

But there were further complications. Sally had to ask the judge for a contingency fund. This was because the children, both gifted musicians, were on means-tested bursaries. This meant that their fees were usually discounted by between 50 and 75 per cent. However, Sally was not working and wanted to find a job. When she managed that, the bursaries would decrease. Her ex-husband opposed the idea of the contingency fund but the judge agreed.

Now that both children have left school, Sally is mightily relieved that her battles are over.

Links

Independent Schools Council (which has information on finding a school): isc.co.uk

Future First: futurefirst.org.uk

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies