Not long ago there was talk about Western economies falling prey to the Japanese economic disease – a reference to endless stagnation in the wake of a massive asset bubble burst. But perhaps that was the wrong comparison.

A compelling new paper from Brian Reading and Diana Choyleva of Lombard Street Research suggests that it's actually China, rather than the West, which is at greatest risk of turning Japanese.

At first glance that sounds far fetched. China's growth might have moderated of late but the economy is still growing at around 7.5 per cent a year. If the country carries on expanding at that rate it will be the world's largest economy by the end of the decade, surpassing the United States. The idea that this powerhouse could be at risk of slumping into decades of disappointing growth in the manner of its Asian neighbour calls for a stretch of the imagination.

Yet Mr Reading and Ms Choyleva see similarities between Japan in the era of its economic miracle between the 1950s and the 1970s and China's growth model today. Both show a large class of repressed savers, with the public essentially compelled to lend cheaply, through the tightly controlled banking system, to the business sector. Both exhibit high investment rates, with GDP growth driven by high rates of capital spending. And both countries rely on strong foreign demand for exports, boosted by an undervalued currency.

The authors also point to structural parallels. They highlight the similarities between the Japanese "keiretsu" system – the tight links between businesses in different sectors involving cross-shareholdings – and the crony arrangements that prevail in much of Chinese industry and government today.

The Japan analogy is, obviously, an unwelcome one for the authorities in Beijing given the implication that stagnation could set in at some point. And looking at the numbers the outlook could actually be still worse for China if this analysis is correct.

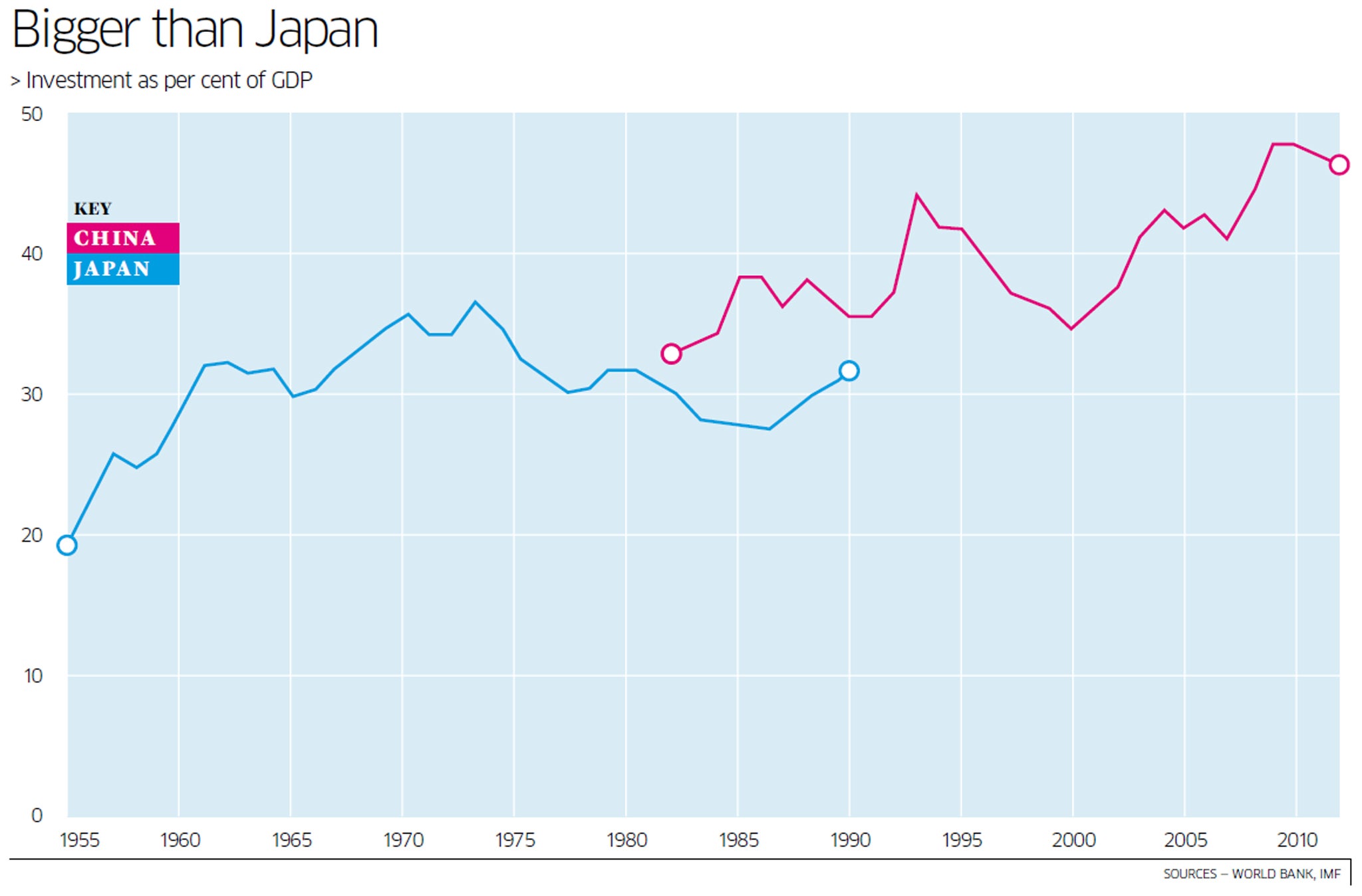

The authors argue that Japan's business and government sector invested to excess in its boom, resulting in a misallocation of resources which, ultimately, turned into a significant drag on growth as banks were encumbered by bad loans. But, as the chart above shows, China's gross capital investment levels in recent decades have actually been even higher. While Japan invested up to 36 per cent of its GDP in its fast growth phase, China has lately been investing close to 50 per cent. As the University of California economics professor Barry Eichengreen puts it: "No economy can productively invest such a large share of its national income for any length of time."

It is a sign of how reliant on investment China has become that trade, though exports are still a large share of GDP, has been making no net contribution to annual growth since the global financial crisis of 2008.

A slowdown could also be more painful for China than it was for Japan if it happens any time soon. When Japan's asset bubble burst in the late 1980s per capita incomes had pretty much caught up with those in the West. In China average incomes are, at present, only around a fifth of those in the US.

China's population is also ageing faster than Japan's did, thanks to the one-child policy, which will add further to the economic pressures of any slowdown. Japan developed world-class manufacturing and technology companies such as Toyota and Sony by the time it stagnated, which enabled it to continue exporting and innovating. China has yet to develop national business champions of similar quality and levels of innovation fall well short of its main competitors.

The China/Japan parallels identified by Lombard Street Research are illuminating. And the conclusion of the authors – that China urgently needs to enact far-reaching structural reforms – is well made. China can't keep driving growth through high savings, high investment and by the accumulation of ever higher mountains of questionable bank loans. Internal consumption needs to take on a bigger role in driving growth. The financial system needs to be liberated and interest rates determined by the markets.

It will not be easy. Japanese governments, despite a democratic political system, found it impossible to take on powerful vested interests. It could prove even harder for a post-Communist authoritarian regime like China, which is only really held together by mutual material self-interest. One previous attempt at banking reform, led by former prime minister Zhu Rongji, was beaten back.

But there is a small light of comfort for China. There was nothing inevitable about Japan's economic malaise over the past 20 years. The country has been cursed by a hidebound central bank which tolerated destructive deflation and whose blocking influence on stimulus has only this year been overcome by Shinzo Abe's administration.

China doesn't suffer from such monetary conservatism. If anything the Beijing authorities have been too willing to stimulate in response to growth slowdowns. And President Xi Jinping and his team, which took power last autumn, certainly say all the right things about reform. Now we wait for the delivery.

In the end, all economies, like Tolstoy's families, are dysfunctional in their own individual ways. But that doesn't mean they can't learn from each other's mistakes. They can and must.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies