The Greek debt turmoil is bad, but don’t panic over the eurozone yet

Economic View

Is it just a Greek thing or is it a euro thing? We cannot yet know but it matters enormously.

Political support in Greece for the austerity programme is already wafer-thin and may disappear in the spring if there is a change of government. Until a few weeks ago it was generally assumed that the country would plod on, basically by squeezing the middle class, until growth at last began to ease the burden.

Now, ironically, as some modest expansion has returned, that is no longer so certain. The possibility that it might abandon austerity, default on its debts and leave the eurozone has suddenly swung back into people’s line of sight. People will have their own views about the odds of such an outcome, but put it this way: you can’t dismiss the possibility. At the moment that possibility is discounted by the markets, but if it were to occur, the plight of Greece would become an issue for Europe as a whole.

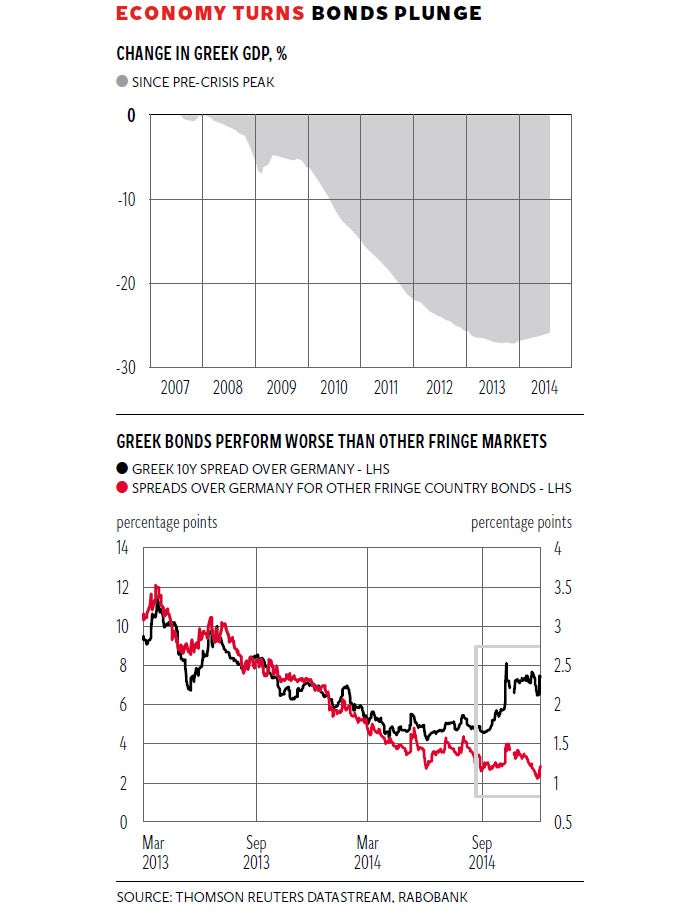

The story is told in the two graphs. At the top you can see the collapse of GDP since the peak early in 2007. The fall is more than 25 per cent. In other words the Greek economy now is only three-quarters of the size it was eight years ago. It is probably true that the peak overstated the sustainable size of the economy, as it was puffed up by excessive borrowings that could never be paid back. Nevertheless, the harsh truth is that no other developed country has experienced such a decline in national wealth since the Second World War. Only in the emerging world have countries experienced reverses on this scale. I don’t think there is much doubt that had Greece not joined the eurozone it would have fared better. The boom would have been less marked and the slump less savage. Whatever view you take about the way in which the euro was introduced, or the way in which the subsequent crisis was handled, this has not been a success for economic policy.

Now look at the second graph. Bond yields are a measure of many things. We have had a 30-year bull market in bonds, with prices rising and yields falling just about everywhere. That bull market almost certainly ended a couple of years ago in the US, UK and some other developed markets, and it seems to be ending about now in the eurozone. Given the different economic performance of the different regions you would not expect cycles to synchronise perfectly.

If, on the other hand, you are focusing just on euro-denominated sovereign debt, what matters is the spread over Germany, the highest-rated sovereign. Obviously there is no currency risk, or at least there is none on the assumption that even were a country to leave the eurozone it would still honour its debts. So the spread is a measure of the markets’ judgement as to the chance of default.

As you can see, through the past 18 months the perception of this risk has steadily fallen for both Greece and the other fringe countries. The risk has been seen as larger for Greece than the others, as the different scales show. Back in March last year there was a 10 per cent gap between Greek 10-year bonds and German ones; whereas the corresponding gap for the debt of the others (weighted by GDP and calculated by Rabobank) was only 3 per cent. By last summer the gap was down to 5 per cent for Greece and 1.5 per cent for the rest. But now, while the spread on the others has continued to fall, coming down to not much more than 1 per cent, it has risen for Greece to around 7 per cent.

The markets are saying that there is hardly any chance of other countries that have received bailouts, such Ireland and Portugal, defaulting. But they are acknowledging that there is a real risk of Greece doing so.

Now, I don’t think one should take these market movements too seriously, for rates jump about in response to every little twitch in the news flow. But they do measure fear and that we have to take seriously.

For the eurozone, the next couple of months will, if you stand back from the pain, be very interesting. The European Central Bank will, or will not, bring in some further measures to try to boost demand. We don’t know how it will reconcile the prohibition it is under of buying sovereign debt to finance governments’ deficits and the desire to bring in some form of quantitative easing (QE). If it were to go down the latter route, as the markets now expect, we don’t know how successful such a policy might be. We do know there is great dissent within the ECB board.

The market view is that for Europe as a whole and assuming the ECB does QE, the higher tide will eventually float off all the boats. Even the laggards will start to grow a bit. But there may not be enough growth to satisfy the electorates. Greece may thus become a bellwether of electoral mood. If, a big if, it were to default on its debts, leave the eurozone, devalue and then grow swiftly, that would really shake things up.

Aim off a little. It does not feel at the moment that the pain in the eurozone is sufficient to provoke such an outcome. Even if it were, Greece might be seen as an outlier rather than a bellwether. The second leg of the crisis of the eurozone feels still to be some way off – perhaps the next global recession. But if the past few days have reminded us of anything it is that politics are unpredictable, and not just in Greece.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies