Hamish McRae: Forget the known unknowns - unknown unknowns are the worry

Economic View: When you make money you are clever; when you lose it, it is someone else's fault

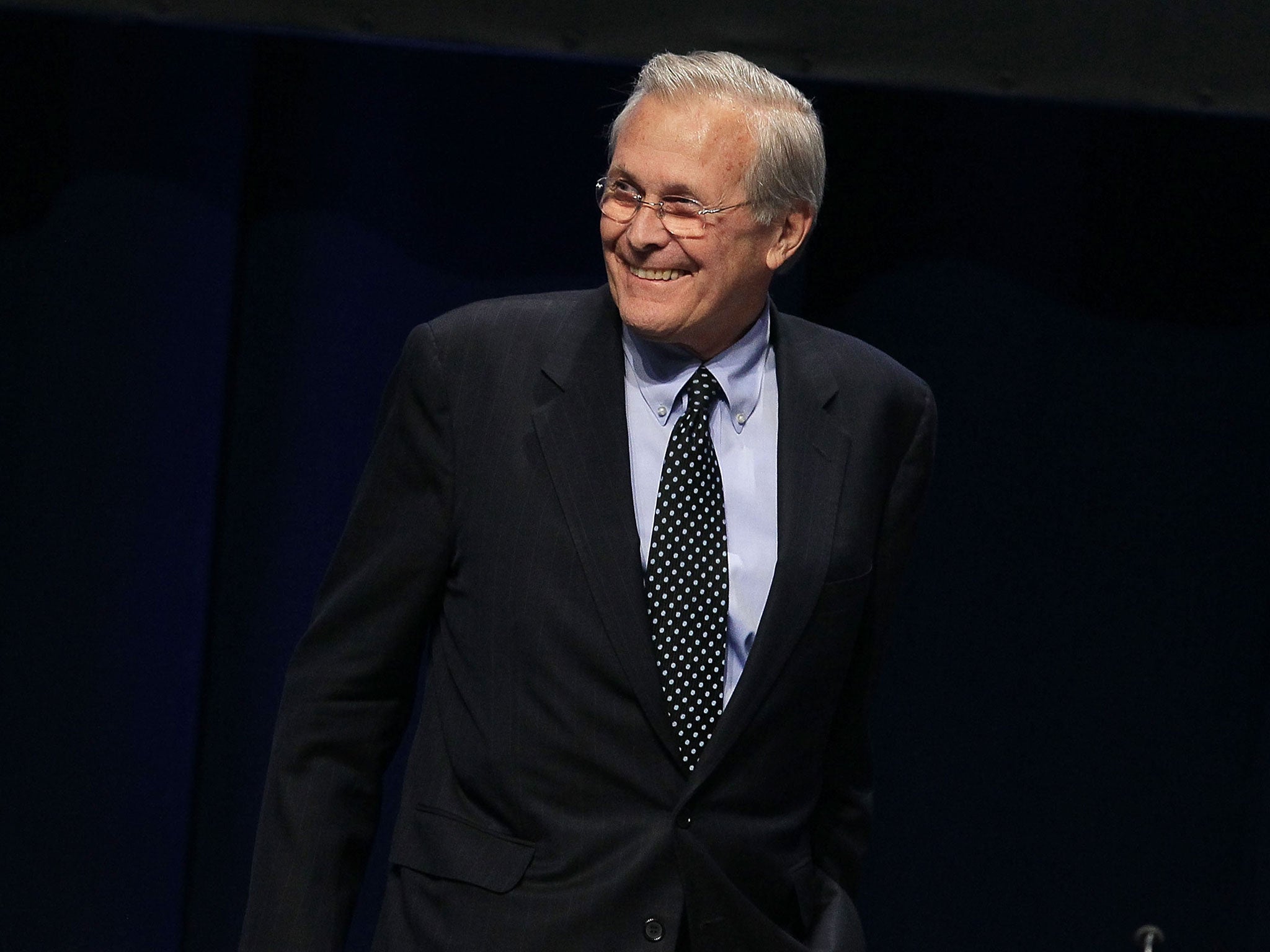

It is the quiet before the storm. One of the pressures overlaying the financial markets in recent weeks has been anticipation of the European Central Bank’s action today on QE – with the worry here that expectations have been raised too high, ensuring disappointment. But a surprise that is widely expected is not really a surprise. It is a “known unknown”, to use Donald Rumsfeld’s expression, not an “unknown unknown”, a risk you don’t even know you don’t know. It is the unknown unknowns that bite investors on the backside.

Every December Saxo Bank, a Danish investment bank founded in 1991, brings out a list of outrageous predictions for 2015. These are, as it puts it, “an exercise in finding 10 relatively controversial and unrelated ideas which could turn your investment world upside down”.

This time they included a crash in the UK housing market; a devaluation of the Chinese yuan by 20 per cent; Mario Draghi resigning from the ECB; Russia defaulting again; and so on. What they did not include was the possibility of the Swiss Central Bank ending its cap on the franc against the euro. Unfortunately, when that happened last week, some Saxo Bank clients appear to have been hard hit. The bank is one of the biggest organisations in retail foreign exchange trading and argues that it warned clients of the risks. But when people lose money, maybe a lot of money, they feel aggrieved. When you make money you are clever; when you lose it, it is someone else’s fault.

To say this is not to get at Saxo or its clients. It is just to point out that things will always come along that are outside normal expectations. The fall of the oil price was at the outside edge of anyone’s predictions – I can’t find any, actually – and that has been the biggest single influence on the world economy in the past six months. It will add around half a percentage point to global growth this year and, more parochially, seems to have closed the case for a rise in UK interest rates until after the election.

This last point is interesting, for were the Bank of England mandate on inflation to be focused on core inflation rather than the CPI, we would probably have had a rise last November. Remember too that the forward guidance in 2013 was that rates would not rise until unemployment fell to 7 per cent. Actually it was not quite as specific as that, but that was the broad message. Well, unemployment is now down to 5.8 per cent and there is no sign of any movement. The two “hawks” on the Monetary Policy Committee who were pushing for an increase in interest rates have now voted for no-change. The result is that the original projections of the timing of the first rise in rates coming either in late 2015 or even in 2016 may turn out to be correct, but for the wrong reason: the reason is not the slowness of the fall in unemployment but the very fast fall in oil prices.

It is worth plodding through all this, simply to show that expectations for the future path of any financial variable – even something as simple as UK short-term interest rates – are highly uncertain. The facts change. Now apply that thought to the future, starting with oil.

The top graph plots the present fall of the oil price alongside that of late 1985 and early 1986, with the price in the earlier period multiplied by four to reflect general inflation since then. Simon Ward, of Henderson Global Investors, argues that of all the sudden falls in the oil price since the early 1980s, this most closely resembles current circumstances. Of the other four, three (1991, 2001 and 2008) were associated with US recessions, and one (1998) with the Asian financial crisis. If this pattern is repeated, oil could bottom below $40 a barrel in the next few weeks, and then climb to $70 to $80 a barrel by the end of this year.

Back in 1985-86, the US Federal Reserve responded to the fall in inflation triggered by the oil price by cutting interest rates, only to have to increase them sharply from the end of 1986 onwards as inflation rose. If you apply that thought to today, we can expect to see sharp increases in interest rates, and maybe an early end to the ECB’s QE programme by the end of this year.

The basic point here is that the oil price is giving a temporary downward distortion to consumer prices here and elsewhere. Once that unwinds, the reverse happens and rising prices give an artificial boost to inflation, to which the central banks will have to respond.

So how sharply might inflation, and hence interest rates, rise? The economics team at Nomura have done the calculations shown in the bottom graph for both the retail price index and the newer consumer price index. The latter goes about the central point of the target band at 2 per cent in the second half of 2016, with the RPI above 3 per cent. It argues: “As oil prices have fallen, the risks of a later start to the hiking cycle have progressively risen.” It does not rule out a rise later this year but thinks the most likely timing will be February 2016, with base rates reaching 2 per cent by May 2017.

My own feeling is that the key will be the US Fed. When dollar rates go up, we will swiftly follow. An economy like ours, with growth close to 3 per cent and unemployment closing in on the 5 per cent levels of the middle 2000s boom, is not an economy that needs near-zero interest rates. But we need cover, and the Fed going up first will give us that.

The timing of increases in rates is a known unknown. However, investors should remember about the unknown unknowns, the outrageous predictions, and make sure that risk is spread as widely and wisely as practicable.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies