Hamish McRae: Interest rates are on the way up at last … but don't hold your breath

Economic View: We will need all sorts of devices in the future to stop government borrowing crowding out everyone else

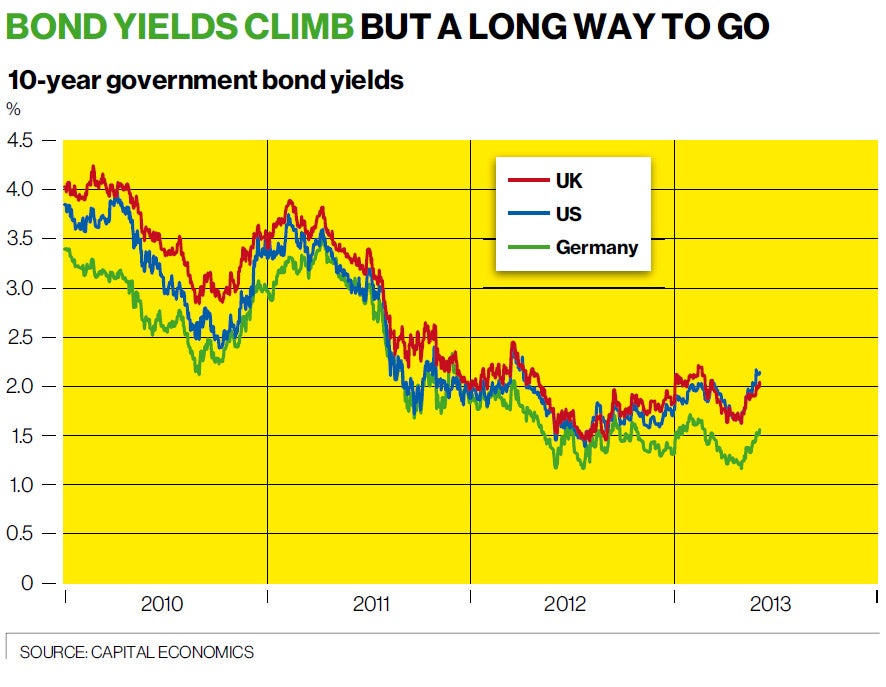

How soon before US and UK long-term interest rates are back to 4 per cent – and what will that do to the economy? It is a question that stems from the sharp rise in both US and UK yields over the past month, for while long-term rates are still exceptionally low by all historical standards, there is a general perception the turning point has been reached. If so, the inevitable question is how steep will the climb be?

Bond markets are so fragmented that the idea there should be a single turning point is a bit ridiculous. It looks as though the turning point for both US and UK government securities came last summer when 10-year yields dropped below 1.5 per cent. They did not dip back to that level in the spring and are now a little above 2 per cent. German Bunds did go pretty much back to their summer levels, though they too have now started to climb. You can see the profile of yields for these three countries in the graph – note how the fall in UK yields started after the Coalition came to office in May 2010, since when they have more than halved.

If you look at other parts of the bond market, emerging market yields, European distressed debt, US non-investment grade bonds, whatever, the turning point looks more like this spring than last summer. But there has been a general upward movement of yields over the past few weeks and this trend seems to be taking hold. The anchor for yields on all bond markets (bar Japan, which goes its own way) remains US Treasuries, and if they go up sharply they will pull the rest up with them.

That leads into a debate about the policy of the Federal Reserve, for the thing that has spooked the markets over the past couple of weeks is the prospect of the US ending quantitative easing. There is a mountain of stuff about Fed policy and there is not much point in trying to add to it here, except to observe three things.

One is that as growth becomes more self-sustaining it is inevitable that the artificial stimulus will be withdrawn. The second is that the costs of ultra-loose monetary policy are becoming more evident, which tip the risk/reward ratio towards ending QE sooner rather than later. The third is that whatever is done it will be gradual and well-flagged. You can surprise markets with good news, but need to prepare carefully before announcing bad.

So let's assume that later this year the Fed will start to withdraw from its very easy money policies, and let's assume that after an interval other central banks will do so too. There is the complication here in the UK that there will be a new governor in post at the Bank of England but the broad structure of monetary policy will remain in place and it would be odd were Mark Carney to try to make any sudden change of direction. In any case the latest UK data is pretty strong. There is a complication in Europe in that different parts of the eurozone require different policies but there is nothing that can be done about that. Viewed overall, though, the second year of recession for the eurozone will inevitably and correctly delay any tightening there. And Japan? Well, it will go its own way as it always has.

So the most likely sequence of events will be that tightening will begin in the US, spread here, and then move to the Continent. How long? It took more than two years to get from "normal" 4 per cent yields to "exceptional" 1.5 per cent yields. So while there is no reason why the yield profile should be symmetrical it would be reasonable to expect another couple of years before we go back to some sort of normality. It will only be "some sort" because two years from now US and UK national debts will be around 90 per cent of GDP, and that overhang will persist for a decade or more. The new normality will be different from the old normality.

That will affect public policy, for governments will be under great pressure to hold down funding costs. The driver for policy will not so much be to boost the economy, more to support their own self-interest. Economies in the middle of a cyclical recovery, which we really should be in within a couple of years, can stand government bond yields of 4 per cent. So too should governments, and it is, after all, what Italy has to pay at the moment, but having had the benefit of borrowing at 2 per cent they will hardly like having to pay double that.

The real debate in the private sector during this era of ultra-cheap money has been whether price matters more than availability. Money is cheap – but you cannot borrow it. Or rather it is only cheap to borrow if you don't need to borrow. The UK government's Funding for Lending scheme has dropped interest rates on mortgages sharply and seems to have increased the supply a little.

But it has not had much impact on the level of commercial lending, which seems still to be falling. Companies are, however, finding ways of expanding output without so much recourse to banks, scarred perhaps by the experiences of banks withdrawing credit lines during the past four years.

If this line of argument is right, expect the next two years to be characterised by three main features.

One will be a gradual rise in all long-term interest rates. Another will be efforts by governments to depress their own costs of funding. And the third will be all sorts of devices to buffer the impact of more expensive money on the mortgage and business loans markets – to stop government borrowing crowding out everyone else.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies