Hamish McRae: Strengthening euro is piling pressure on the strugglers

Economic View: There is the prospect of several years of depression for much of southern Europe. Even France is in trouble

Currencies are on the march again and though we may not be entering a currency war, as the deputy chairman of the Russian central bank warned today, we certainly look to be heading into a period of currency insecurity. Viewed globally the most dramatic change of the past few weeks has been a sharp fall in the yen, as the new Japanese government seeks to lift demand by improving the competitiveness of the currency.

But nearer home there are two particular issues that affect us directly here. One is the concern that sterling might be heading for a fall; the other that the euro might rise further and undermine whatever recovery the eurozone might hope to experience.

Sterling first. Back in November Sir Mervyn King said that sterling's appreciation over the previous year was "not a welcome development". Since then the gradual erosion of the "safe haven" status of the pound and of UK government securities seems to have capped the rise. But whereas gilts have really fallen quite sharply, sterling has been broadly flat since then.

It is as though the markets noted what he said and then, rather than selling the pound, they sold government securities – though I suspect that the slippage of the Coalition's deficit-reduction programme and the probable loss of the UK's AAA debt rating had more to do with that.

In the past few days, however, these movements have been reversed. Gilts have recovered a bit, reflecting renewed fears about the world economy this year, but sterling has weakened. Indeed there have been renewed suggestions by market analysts that the pound might be heading for quite a sharp fall.

The practical question is whether sterling faces a period of modest weakness, which would be manageable enough – if you believe the governor, quite welcome – or whether something bigger is about to happen. The issue in the currency markets remains that this is a beauty parade to find the least ugly, for there are solid reasons to distrust the dollar, the yen, sterling and the euro. They just happen to be different ones.

The common-sense view about sterling is that it may well weaken a bit in the months ahead but it is more or less fairly valued at the moment. It may be a bit overpriced but not ridiculously so. What about the euro?

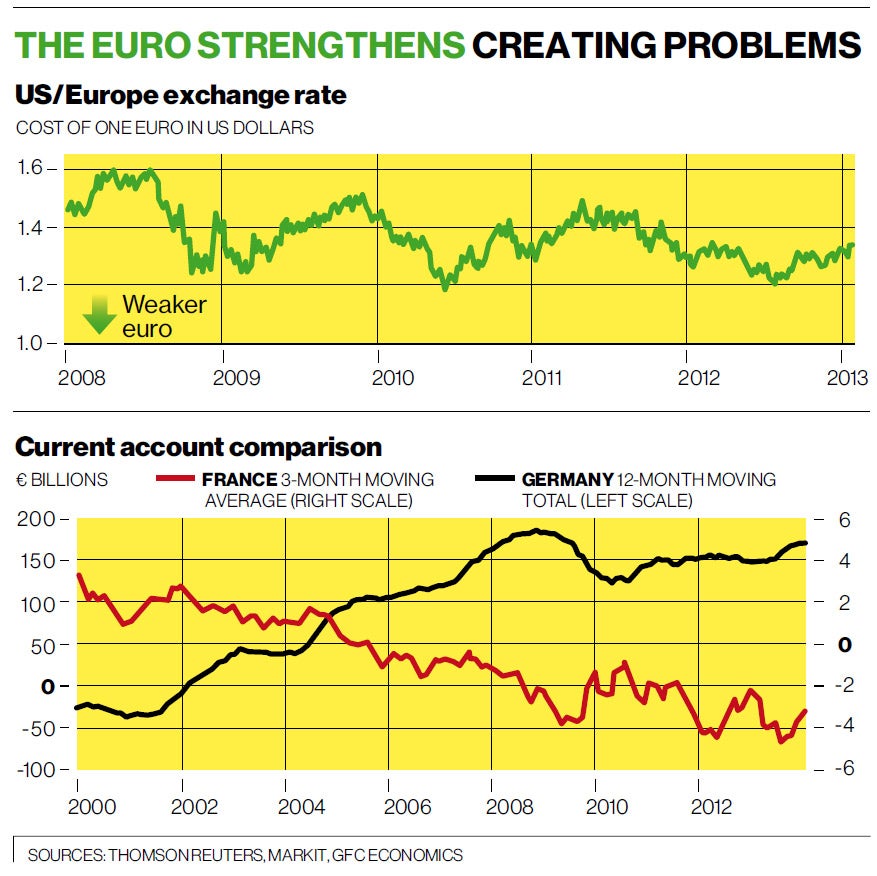

Well, Jean-Claude Juncker, prime minister of Luxembourg, has just described the euro's value as "dangerously high", strong language indeed. But while at around $1.33 it is the highest for nearly a year against the dollar, on a longer view it would not seem to be particularly out of line, as you can see from the first graph. The problem is that it may be dangerously high for some members but not for others.

A rough-and-ready way of assessing whether a currency is too high or too low is to look at its current account position. Now we all know that the euro is too high for the struggling economies of southern Europe.

Were Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal not in the euro they would have devalued to regain competitiveness. But they can't. However, there is a growing imbalance between even the two strongest large European economies, France and Germany. You can catch a feeling for that in the other graph. This shows the contrast between the current account position of the two countries, with France moving from surplus to deficit and Germany heading in the other direction. Over the 12 months to November the German current account surplus was €170bn (£141bn).

What does all this imply? I think the first point to make is that the markets are now much more optimistic about the eurozone surviving intact, or at least only losing Greece, for the next four or five years, than they were last summer.

You don't need to accept the swagger of the president of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso – "in 2013 the question won't be if the euro will or will not implode" – to acknowledge that.

The benefit of this reassessment of the currency has been a sharp fall in the borrowing rates of the distressed members. But there has been a cost and that is the prospect of several years of depression for much of southern Europe. Even France is in trouble.

The Ifo Institute, based in Munich, has just produced a report on the economic costs of the success in stabilising the euro. It notes that France's manufacturing industry is now only 9 per cent of GDP, smaller even than in the UK, that its car industry is fighting for survival, and that unemployment is rising to record levels.

"France's basic problem," the Ifo Institute's head, Professor Hans-Werner Sinn, comments, "is that the wave of cheap credit that the euro's introduction made possible fuelled an inflationary bubble that robbed it of its competitiveness."

The same applies to Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece. So what gives?

"In order to become cheaper, a country's inflation rate must stay below that of its competitors, but that can be accomplished only through an economic slump. The more trade unions defend existing wage structures, and the lower productivity growth is, the longer the slump will be. Spain and France would need a 10-year slump, with annual inflation 2 per cent lower than that of their competitors, to regain their competitiveness."

It is true that the Ifo Institute has been one of the most strident critics of the way the euro has been managed but the maths are the maths. Its argument is that France has to adopt similar policies to those that Germany did in the early 2000s, cutting back on costs, particularly wage costs, to regain competitiveness.

"Unfortunately, thus far, there is no sign that the crisis countries, above all France, are ready to bite the bullet. The longer they cling to a belief in magic formulas, the longer the euro crisis will be with us."

That is stern stuff and we will have to see how the France government does react.

But the key point remains: the greater the faith the world's markets have in the euro, the greater the pressure on its weaker members.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies