Hamish McRae: Things are looking up, so why this gloom from IMF?

Economic View: How well we in Britain do will largely be determined by what happens to the rest of the world

The mood has lightened a little more. Every few days, there is another bit of positive information about the state of the global recovery – or rather the positive stories well outnumber the negative ones. Recent ones include rising sales of homes in the US and UK, higher-than-forecast profits for large US companies, declining long bond yields for Spain and Italy, and of course the continuing strong labour market recovery in the UK.

This uplift in economic prospects has been reflected in the rise in share prices on all the major share markets – the FTSE 100 index got to within a point of 6200 in early trading – and has also been evident in the lighter tone in a number of speeches by officials, including Sir Mervyn King. The minutes of the Bank of England monetary policy committee are mildly upbeat. And even if you don't buy the line from European leaders that the euro crisis is over, the dangers of a break-up have receded for the time being at least.

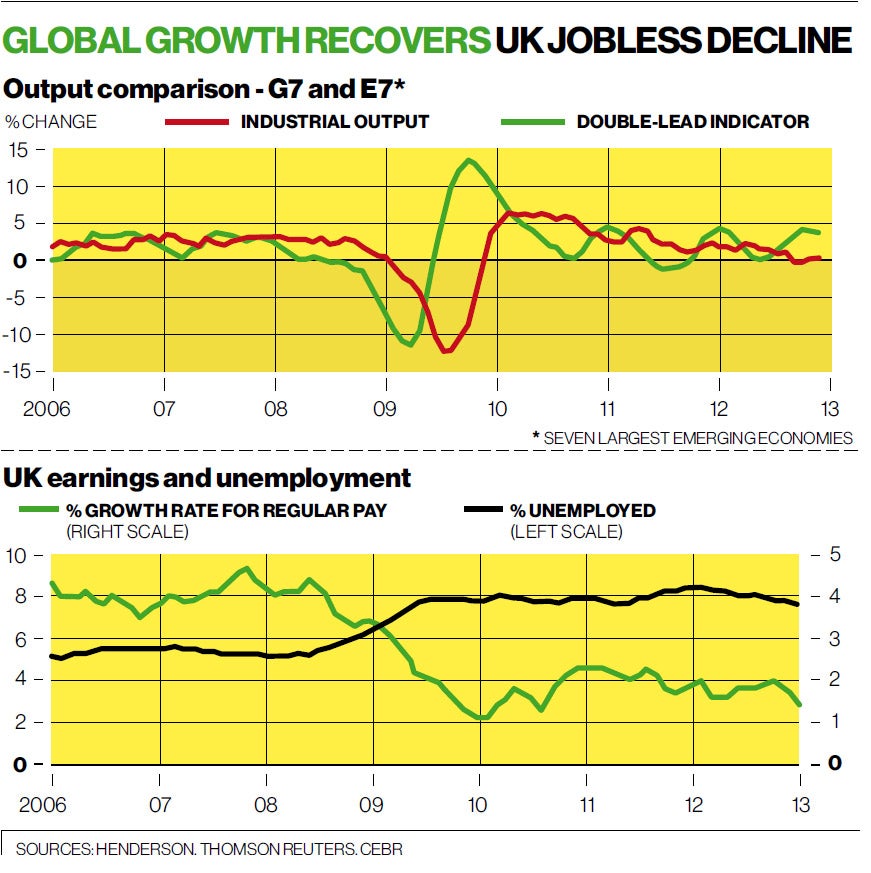

If you think world rather than UK, US or Europe, the calculation of G7 plus E7 output is a useful one. The G7 we know about, the world's seven largest developed economies; the E7 is simply the world's seven largest emerging ones. Put the two together and you are covering more than 80 per cent of global output. Some numbers for what has been happening to industrial production for these two umbrella regions have been put together by Simon Ward at fund managers Henderson, and they are shown in the top graph.

He has also calculated a "double-lead indicator", designed to give early warning of turning points, with an average lead of five months. That did, as you can see, give a warning of the slowdown that become evident last summer but now has clearly turned upwards. This would suggest the global growth will strengthen as we move through the year.

How well we in Britain do will largely be determined by what happens to the rest of the world. Of course we may underperform in relative terms or we may outperform, and over a long period the difference of half a percentage point either way makes a massive different to prosperity, levels of employment and unemployment, public finances and so on.

But on a one-year or two-year outlook, whether we do a bit better or a bit worse than the rest of the pack does not change things much.

That said, the latest figures here are quite encouraging. The continued strong rise in employment was met with a curiously sour response by most commentators. It was declared to be unexpected, which simply means that the commentator had been reading the economy wrong. Many of the responses included the word "but" – but wage grown was very low, but the improvement was unlikely to last and so on. The plain fact remains that the economy has added 97,000 full-time jobs in the past three months, has cut unemployment to 7.7 per cent, and has more people in jobs than ever before in our history. There are half a million more people working than a year ago. Total hours worked are up too.

On Friday, we may well get bad GDP figures for the final quarter of last year, suggesting that the economy barely grew at all, maybe even shrank, during 2012. But common sense says that if there are half a million more people in jobs and that more hours are being worked, it is implausible that the economy should not be growing at all.

The picture of more people at work is confirmed by reasonably strong receipts from National Insurance Contributions and from an increase in VAT receipts too. What is true is that pay increases are very low; in real terms (i.e. after inflation) earnings are indeed falling. So the squeeze on living standards goes on.

So what can be done to improve UK growth? One obvious candidate would be to cut inflation, for that is chipping away at living standards. A problem is that quite a lot of the inflation comes from administered prices: rail fares, higher utility prices, local authority parking charges, university fees and so on.

It is not quite fair to say this is inflation created by government policy, but it is not largely created by the market. Whatever view you take of the coalition's policy on renewable energy, the harsh fact is that it puts up prices to a higher level than they would otherwise be.

This is one of the themes in tonight's Gresham lecture by Prof Doug McWilliams, who is also head of the Centre for Economics and Business Research consultancy. He argues that the government needs to focus on getting the cost of living down, noting that cost of consumers' expenditure is 11 per cent higher than the OECD average. The two areas where the gap is greatest are transport (31 per cent) and housing and utilities (18 per cent). Suggested measures to cut the cost of living include planning reform, increasing investment in social housing, and bringing down the cost of both private and public transport.

The thing I find most interesting here is the idea that inflation is a government responsibility. Governments impose costs on society in response to political demand without paying attention to compliance costs, which are inevitably passed on in higher prices. This is nuts, and it needs to said.

If there is a puzzle about the UK economy, in that the official GDP figures do not square with what seems to be happening on the ground, this puzzle is repeated on a global scale in the new World Economic Outlook forecasts from the International Monetary Fund.

The IMF has trimmed its growth forecast for the world this year to 3.5 per cent; it expects the eurozone economy to shrunk by 0.2 per cent instead of growing by the same amount; and it has cut its forecast for the UK to just 1 per cent.

All this may be turn out to be right, but I do think you have to ask why the IMF's is forecasts are becoming less optimistic at the same time as the world's financial markets are becoming more optimistic.

Of course, the markets may be wrong, but just occasionally so too are economists.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies